Introduction

Geopolitical competition is currently reshaping the global economy, and economic power and means are increasingly used for political purposes. Simultaneously, the fast-changing and increasingly complex contemporary geopolitical context has shifted increasing attention to economic security. Following these developments, it can be said that the economy and (geo)politics are increasingly interwoven. Hence, it is not surprising that economic security has been receiving increasing attention from both European as well as Dutch policymakers. It includes among other things foreign takeovers and investments, trade espionage, security of energy supply, etc. Moreover, in the absence of global leadership, global norms and standards are currently under pressure. There are numerous examples that demonstrate this, such as the trade war between the United States (US) and China, and concerns about the Chinese technology giant Huawei, which is accused of being a tool for espionage by the Chinese government.

Given the increasing focus that has been put on economic security, the second Global Security Pulse related to the HCSS/Clingendael Strategic Monitor 2019-2020, centered around this topic. Subsequently, this accompanying research paper explains and justifies the underlying conceptual choices that were made, and reflects upon the results of the Horizon scan. It consists of four parts. Firstly, it will conceptualize the topic of economic security, as it was understood in the Global Security Pulse. Secondly, it provides the results of the Horizon scan, by discussing several threat developments. Thirdly, it will show the outcomes of a multi-factor threat assessment and a multi-year regime analysis related to the topic. The paper concludes with a paragraph on the implications of these trends and developments for the formulation of Dutch foreign and security policy.

Conceptualizing economic security

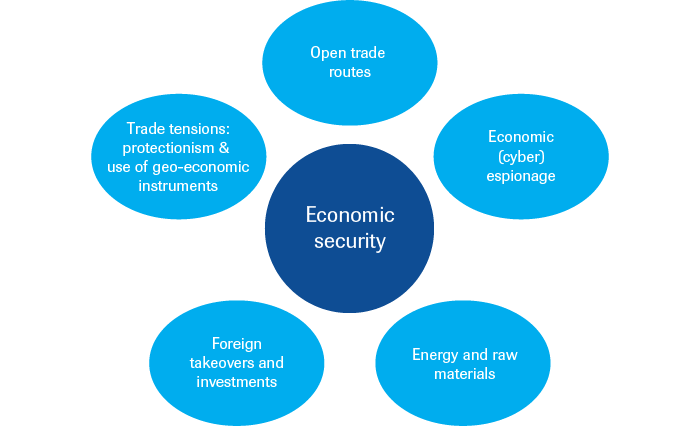

Economic security is a very broad term. In order to determine what is deemed to constitute ‘economic security’, the authors have looked at various European and Dutch strategy and policy documents.[1] Essentially, guaranteeing economic security revolves around achieving the following five objectives (see Figure 1):

The Global Security Pulse looked for new signals that relate to these five elements of economic security. In addition, the Pulse tried to discover new or important signals that can tell us something about the state of and developments within the international order, and in particular with reference to the free-trade regime.

Development of the threat

Based upon the Horizon scan, a number of important threats can be identified. Among these include Chinese economic espionage, Chinese aerospace dominance aimed at economic expansion, Chinese Foreign Direct Investments (FDI’s), potential conflicts in the Suez Canal affecting trade routes, cyberattacks against Dutch vital infrastructure, heightening geopolitical tensions regarding Nord Stream 2 pipeline, increased activity in the Artic region, and pirate attacks in West-Africa. This section will elaborate on how the abovementioned potential threats might develop.

Firstly, the Chinese Communist Party and Chinese companies are becoming less covert in their economic espionage. Although China has been conducting espionage for years, it is currently ramping up its espionage activities. In particular the number of corporate cyberattacks outside China has recently soared and costs have risen accordingly. The Netherlands General Intelligence and Security Service (AIVD) has called China “the biggest threat when it comes to economic espionage”.[2] China is in particular interested in Dutch companies that operate in the high-tech, energy, maritime and life sciences & health sectors. A particularly concerning development is that China’s Ministry for State Security (MSS) is working more closely with Chinese enterprises and uses cover organizations such as universities, trade associations and think tanks. China has become more aggressive and seems to care less if it gets caught or if people go to jail. It also uses non-cyber means of espionage, such as recruiting employees to steal information or the theft of specific technological inventions (for example genetically modified rice seeds). These developments show how advanced China has already become in the field of espionage.[3]

In addition, China is expanding its aerospace program aimed at economic expansion, thereby achieving greater aerospace dominance. China’s space ambitions are centered on wealth creation (instead of space exploration) through a space-based economy, as stated in the White Paper issued by the Chinese government. In January this year, China’s Chang’e 4 was the first to land on the far side of the moon, with an extended goal of establishing a permanent lunar research station by 2035. This lunar base will be used for mining, deep space exploration and exploitation. Although technical difficulties remain, China aims to launch a solar power system and extract metals such as ores. The political implications of its potential space dominance are expected to become even greater, as space is also one of the new dimensions for military competition.[4]

Another field where China has become increasingly active, is through increasing prominence of Chinese FDI in the EU, thereby increasing its political influence. Greece, Portugal and Malta have already signed deals with China, in sectors ranging from energy to transportation, in addition to significant Chinese presence in insurance, health and financial services. Italy – the first G7 member and the third largest EU economy – has signed deals worth €2.5 billion, and that figure can potentially rise to €20 billion, since the two countries pledged closer economic cooperation, particularly in the fields of connectivity, (energy) infrastructure and trade. In its wake, Luxembourg has signed an agreement on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Even though these investments are relatively small, and projects may fail, the political significance may be greater. In other countries similar investments have led to the emergence of debt traps or divergent voting in international organizations. In the future, the EU will have to deal with China on other issues as well, such as export controls and defense cooperation. The big question is: is the EU ready for this?[5]

Next to concerns about China’s economic policies, there are increasing worries about safeguarding trade routes. Conflict in surrounding countries of the Suez Canal and the influence of Russia and China in the region can potentially affect trade routes. For example, unrest in the Horn of Africa could threaten navigation in the southern entrance to the Red Sea, thereby possibly affecting access to Egypt’s Suez Canal. Moreover, Egypt has been making diplomatic overtures to Moscow and Beijing, as the US has become less active. Egypt and China have already signed deals worth $18 billion as part of the BRI. Egypt recently also signed deals with Russia to establish a Russian industrial zone around the Suez Canal. This Chinese and Russian influence endangers access to the important trade corridor and threatens Egyptian economic independence.[6]

Of a completely different nature are potential cyberattacks against the Dutch vital infrastructure. These attacks are becoming a serious security challenge. For example, the Netherlands Court of Audit issued a report stating that vital Dutch water defense structures such as the Delta Works, locks and pumps, intended to protect the Netherlands against flooding, are inadequately secured against cyberattacks. If a hostile country or terrorists take over digital control of these structures, they can potentially have the power to flood the Netherlands. Moreover, the energy sector has become increasingly vulnerable to cyber threats as a result of rapid digitalization. In addition, up-and-coming artificial intelligence (AI) malware will increasingly usher in a new era of threats to the energy industry, allowing hostile actors to wreak havoc on a scale hitherto unknown. AI-driven malware can be employed with unprecedented accuracy and is very hard to stop.[7]

Next to abovementioned threats, there are also some threats to be identified in the geopolitical arena. In the first place, heightening geopolitical tensions abound the Nord Stream 2 pipeline project among EU and NATO partners. Even though the construction of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline is at an advanced stage, the debate surrounding the commercial and geopolitical implications is heating up, as the EU is becoming more aware of the risks. The debate highlights geopolitical tensions within the EU and NATO, but the private sector is very much engaged in the debate as well. Germany’s role as an advocate of Nord Stream 2 has been heavily criticized, for example by Poland. The European Parliament has adopted a resolution urging Germany to halt the project. Proof of heightened geopolitical tensions can also be found in US policy, in which it is preparing to sanction EU firms financing or co-financing Nord Stream 2. This can potentially also hurt Dutch firms. Another source of debate is the Baltic region. In January, Russia launched a Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) power plant to make its Kaliningrad exclave self-reliant when NATO members unplug the power grid. The exclave is at risk of becoming the stage for a new gas “Cold War”.[8]

Secondly, the Artic can also be identified as an area of geopolitical tension. Both China and Russia are expanding their presence in the region. China has announced that it will start building its first airport in the Arctic. Russia has given the state corporation Rosatom the leading role in the development of the Northern Sea Route. The company has recently opened a base in Murmansk to monitor and regulate ship traffic. Russia is also renewing and reactivating Cold War military infrastructure in the Arctic. In addition, the countries are increasingly seeking mutual cooperation in this area. China is seeking to integrate its ‘Polar Silk Road’ – a predominantly Sino-Russian partnership – into the greater BRI. A major component is the development of joint ventures with Russia in resource extraction, including fossil fuels and raw materials. The ‘Polar Silk Road’, however, seems to be focused mainly on opening up trade routes. Moreover, Russia’s real threat has not been established: China will likely gain more from their collaboration, and Russia’s ventures are too reliant on stable oil prices.[9]

A final potential threat to our economic security stems from pirate attacks and armed robberies in West Africa. Lately, the number of pirate attacks and armed robberies has been on the rise, whereby West Africa has overtaken the Horn of Africa as Africa’s piracy hotspot. According to the International Maritime Bureau’s annual report, pirate attacks and armed robberies rose worldwide in 2018 due to a surge in attacks off West Africa, despite declining number of attacks in other parts of the world. Petro-piracy in particular is a growing risk off West Africa and can affect oil supplies to the EU.[10]

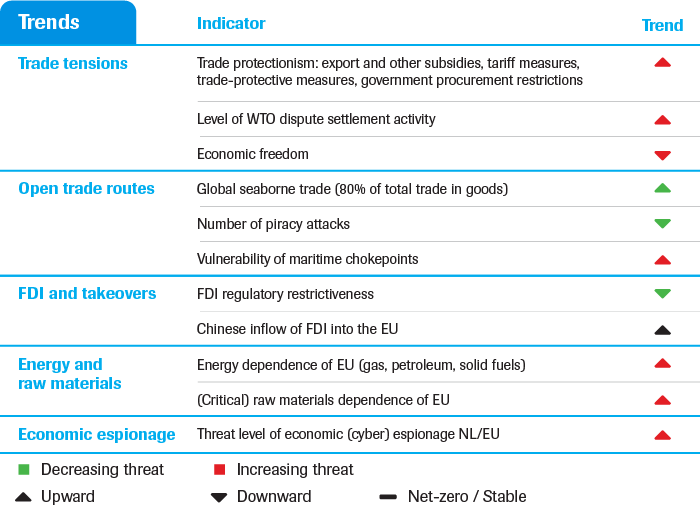

Table 1 provides a multi-factor threat assessment, in which the expectations with reference to the development of (some of) the above discussed trends are summarized.

Developments in the international order

Not only our economic security as such is under threat. Taking a more broader perspective as a starting point, a few trends can be identified that severely affect the international order. In particular, this applies to the free-trade regime, which has found itself under severe pressure over the past few years. Hence, this section discusses the most important developments that impact the (functioning of) the international, economic order.

Probably the most evident example of increasing tensions in the international economic system, is the chronic crisis surrounding the World Trade Organization (WTO). The US, under President Trump, is blocking the appointment of new members of the WTO Appellate Body, the organization’s dispute settlement mechanism, thereby risking an existential crisis. Within a few months it could paralyze 23 years of WTO enforcement, the keystone of international efforts to prevent trade protectionism. This is particularly worrisome at a time of heightened global trade tensions. Some argue that without effective dispute resolution there is a risk that the WTO system will collapse. Meanwhile, states are turning towards plurilateralism. A telling example is the recent announcement by 76 member countries that they will start independent negotiations on e-commerce, because in their opinion the WTO lacks vigor. All this highlights the need for reforms within the WTO.[12]

Next to potential economic effects of China’s BRI in European countries, such as potential debt traps, the BRI is also causing political discord within the EU. Thus, the BRI has been described as a deliberate tactic by Beijing to undermine EU unity. This ‘divide-and-rule’ tactic can potentially pit European powers against each other. Even though major European countries are increasingly vocal against China’s unfair trade policies, investments and unfulfilled reform promises, deals with the Chinese are still being signed. In total 15 of the 28 EU member states have signed up for the BRI. Italy has signed deals worth €2.5 billion and that figure could rise further. The issue is dividing the EU. EU member states such as Germany and France have pushed for tougher screening criteria for Chinese investments, while other countries such as Greece and Portugal have adopted a more lenient approach.[13]

In addition, following the debate on Chinese FDI, EU industrial policy is back on the agenda. There is growing concern about foreign investors, notably state-owned enterprises, who take over European companies for strategic reasons. In light of this, the EU has adopted a new framework for screening FDI into the EU, which has come into force in April 2019.[14] It provides a means of detecting and addressing security risks that may be posed by foreign takeovers of critical assets, technologies and infrastructures. France and Germany are leading the push for a common strategy to deal with competition from Chinese state-led firms. In March 2019, the European Commission presented a new strategic 10-point action plan, marking a new approach in which the EU is openly moving to protecting itself better in trade relations with China. Other drivers of this debate are geopolitical consequences of the energy transition.[15]

Another development within the international order is that China has become a standard-setter in the field of technology. The risk that follows is that some fields, such as IT, are splintering into US and Chinese spheres of influence. The strategic rivalry between China and the US is thus fast evolving into an arms race for technological dominance. China is highly proactive in influencing global tech standards (from AI to hydropower) and exporting its own standards along the ‘Digital Silk Road’. European economies may find themselves increasingly dependent not just on US but also on Chinese digital technologies. This might also affect military operators, as they are increasingly dependent on technologies from the commercial sector (dual use technologies). Also, Chinese companies are intensifying their influence in international standard-setting bodies. State-sponsored efforts to shape international standards have been ongoing since the country entered the WTO. A report by the UN World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) showed that China and the US are leading the global competition to dominate AI. Political trends in both countries imply that a growing divergence in IT systems and standards is likely.[16]

Following China’s increasing assertiveness in the international system, another factor that plays a significant role is that the EU and the US are adopting diverging strategies when it comes to China. Despite having similar concerns about China’s economic policies, the US and EU barely coordinate their policies with respect to China. The US is in a trade war with China, and European leaders are increasingly alarmed by China’s economic influence on the continent. Nevertheless, because of frictions between the EU and the US, there has been little or no cooperation or coordination in their strategies. While they share many of the same concerns (and both used to be defenders of the liberal order), they are far apart on what to do about it. While the US is imposing tariffs, the EU wants to preserve the WTO as the prime forum. However, increasing attention is being devoted to this problem and there are signs that efforts are being made to curb it.[17]

Another driver of shifts in the geopolitical order is energy transition. As countries become less dependent on oil, the energy transition towards renewable energy will alter the global distribution of power and relations between states. It will also influence the risk of conflict and the social, economic and environmental drivers of geopolitical instability. The weight of energy dependence will shift from global markets to regional grids. The Baltic states, for instance, want to connect their grids to those of continental Europe in order to decouple their electricity systems from Russia. This move also has geopolitical motives. While there are new initiatives emerging to promote multilateral cooperation and boost renewable technologies, alliances are also forming between oil-producing countries. For instance, Russia and Saudi Arabia have continuously strengthened ties, especially following the Western sanctions against the Russian energy sector. There are signs that Saudi Arabia wants to formalize the pact between OPEC and Russia. The two countries are discussing huge investments in each other’s oil industries.[18] In addition, next to energy transition being a driver of shifts in the international order, oil itself is also still being used as an instrument in geopolitics. The recent attacks on the oil facilities in Saudi Arabia demonstrates this, as this reveals tensions between different (state) actors that are active in the region.

A final element that (potentially) affects the international order, is that the advance of digital technology is increasingly dividing the world into haves and have-nots, which is impeding regime development. Digital technology (such as AI, the Internet of Things, 3D, Block Chain, etc.) is reshaping economic activity in every corner of the globe. However, this change is taking place at different speeds, depending on each country’s degree of readiness to participate in the digital economy and the extent to which each can benefit from it. Although some argue that there are signs that the so-called digital divide is narrowing, there is clearly still a great disparity worldwide. This indicates that the digital divide between developed and developing countries can act as a barrier to more economic integration in the digital realm. The trends seem to result in market concentration, first-mover advantages for incumbent firms and barriers to entry into the relevant markets.[19]

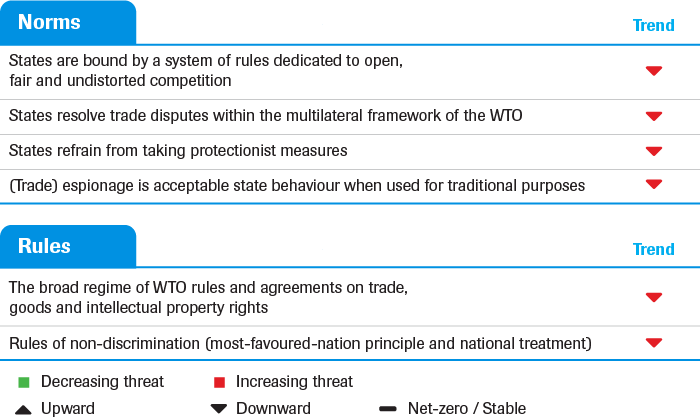

Table 2 provides an overview of the multi-year regime analysis. It shows the expectations regarding the development of the norms and rules. Roughly, the figure corresponds to the above discussed developments in the international order, and in particular the free-trade regime.

Conclusion

What can be derived from the discussion above is that there are several trends and developments that can be identified as affecting our economic security. What is apparent is the prominence of China in these developments. On several aspects, such as economic espionage and FDI investments, China is becoming more assertive. In addition, China is taking a prominent place with reference to several developments in the international order, among which the trade war between the US and China, standard-setting within the field of technology, and the expansion of the BRI in European countries. Hence, it can be said that our economic security – essentially revolving around preventing trade tensions, keeping trade routes open, countering economic (cyber) espionage, ensuring the supply of energy and raw materials, and safeguarding national security when investments are made or companies are taken over – will to an increasing extent be dependent upon China. In particular, security will be dependent on Chinese economic policies, but also more broadly on China’s stance towards and activities in the international order. In addition to the dependence of our economic security on Chinese attitudes and activities, there are, of course, other developments that can be identified. For example, the Dutch vital infrastructure is vulnerable for cyberattacks. This is demonstrated by the fact that the water defense structures, such as the Delta Works, are inadequately secured against cyberattacks, which leaves room for hostile actors to take over digital control, which can potentially lead to flooding of the Netherlands. Another example is that energy transition will drive geopolitical tensions in the upcoming years, as the shift towards renewable energy will alter the power relations between states significantly, which will affect the international (economic) order.

Consequently, Dutch and European policymakers will, in the upcoming years, be confronted with several challenges that need to be addressed. For example, as China is becoming more assertive and thereby a more prominent actor internationally, the EU and the Netherlands will need to be able to deal with China on other topics than FDI, such as export control or defense cooperation, as well. Furthermore, as cyberattacks become more common, Europe’s and the Netherland’s vital infrastructure should be better protected against challenges coming from technological developments such as AI. In addition, questions such as how can the EU stand its ground in the ongoing global standard-setting competition should receive careful consideration. In dealing with these different types of challenges, it is important that EU member states maintain their unity, as only then can these challenges be addressed effectively.