List of Abbreviations

| A2AD |

Anti-Access/Area-Denial |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ASEAN |

Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

| CBRN |

Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear |

| CRISPR |

Cluster regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| CSIS |

Center for Strategic and International Studies |

| DIY |

Do-it-yourself |

| ECFR |

European Council of Foreign Relations |

| ESPAS |

European Strategy and Policy Analysis System |

| ETHZ |

Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zürich |

| EU |

European Union |

| GBVS |

Geïntegreerde Buitenland -en Veiligheidsstrategie |

| IFC-IOR |

Information Fusion Centre - Indian Ocean Region |

| IGO |

Intergovernmental Organization |

| IISS |

Israel Institute for Strategic Studies |

| IMC |

Interstate military competition |

| ISIS |

Islamic State in Iraq and Syria |

| MENA |

Middle East and North Africa |

| MSC |

Münich Security Conference |

| NATO |

North Atlantic Treaty Organization |

| NCTV |

Nationaal Coordinator Terrorismebestrijding en Veiligheid |

| NSC |

National Security Council |

| NSS |

National Security Strategy |

| UAE |

United Arab Emirates |

| US |

United States |

| WEF |

World Economic Forum |

| WMD |

Weapon of Mass Destruction |

Executive Summary

All countries have procedures and – in some cases – methodologies to identify, analyze and (explicitly or implicitly) prioritize threats to their national security. The outcome of these efforts is typically one or more high-level documents in which the responsible national security bodies provide authoritative statements on threats facing the country. As part of the Dutch Strategic Monitor effort, HCSS was asked to take a closer look at how other actors perceive their threat environments and to what extent they might differ from their Dutch equivalents. Based on an analysis of a.) national security and defense strategies published by other actors, and b.) survey-based threat environment analyses published by world-renowned think tanks and/or institutions, this study sets out to address the following research questions:

We have analyzed 38 post-2016 individual documents sourced from 11 countries and six world-renowned think tanks and/or intergovernmental organizations. Each country’s security perspective was analyzed based on two documents; one published by state institutions, and one published by a locally based think tank. Each country’s documents were analyzed by a standardized rubric, which aimed to extract a long-list of identified threats – and countries’ perceptions thereof – in order to provide insights with the potential of challenging preconceptions underpinning the Dutch threat perception framework.

Threats

With regards to allies’ and adversaries’ perceptions of threats relating to the six central threat categories in the GBVS, several observations stand out on a threat-by-threat basis:

IMC. The threat of military confrontation is identified by China, Finland, India, Israel, Japan, Russia and the United States. The European Strategy and Policy Analysis System (ESPAS) and Munich Security Conference (MSC) additionally note that the threat of interstate armed conflict erupting is on the uptick. Among these actors, the most held view – that is shared by the Netherlands – is that an increase in interstate competition increases the risk of military competition. On the one hand, China, Japan, Russia, and the US place an emphasis on their competitors’ efforts at military modernization, pointing towards increasing defense budgets and the unveiling of cutting-edge (conventional) weapons systems as signs of aggression. India, Israel, and Japan, view interstate competition through the lens of regional dynamics in their neighborhood and the regional insecurity it is likely to exacerbate. This differs from the Dutch perspective, which places an emphasis on IMC’s broader negative effects on the rules-based international order. Outside of the ESPAS and the MSC, virtually no actors share (or explicitly formulate) the Dutch view that IMC as a phenomenon is serving to erode the international legal order.

Conflict in cyberspace. Australia, Finland, Israel, Japan, Singapore, the UAE and the US all explicitly elaborate on the threats posed by malicious actors’ activities in cyberspace, as do the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), ESPAS, MSC, and World Economic Forum (WEF). Australia, the CSIS, Finland, Israel, Japan, the UAE, the US, and WEF emphasize systems’ interdependencies in critical infrastructure as a factor which serves to heighten their societies’ vulnerability to cyberattacks.[1] In further alignment with the Netherlands, Israel, Japan, the UAE, the US and the WEF subscribe to the notion that the cyber domain’s penetration of virtually all spheres of life creates further vulnerabilities and/or vectors for cyberattacks. The sentiment that cyber and/or IT-related innovations are likely to upend existing power dynamics, whether military or otherwise, constitutes a marked departure from the Dutch view on cyber threats. Whereas the Netherlands perceives cyber threats almost exclusively through the lens of cyberattacks, CSIS, ESPAS, Japan, the UAE, and WEF take a wider view of threats originating from within the cyber domain. These actors view the cyber domain as forming a likely backdrop for interstate competition, and cluster technologies such as 5G and AI beneath the “cyber” moniker.

Hybrid conflict and economic security. Most actors which identify hybrid tools and/or grey zone operations as a threat identify the phenomenon of unwanted foreign influences. CSIS, the European Council of Foreign Relations (ECFR), ESPAS, Finland, Japan, the UAE, and the US touch on influence campaigns as a threat. Common within this subset of actors is a focus on a) new technologies, and b) vulnerabilities brought about by societal openness – both factors which the Netherlands outlines explicitly. The Dutch perception that hybrid tactics increasingly take the form of – and infringe on – its vital economic processes is sparsely shared. Finland identifies the disruption of critical supply chains as a threat deriving from the increasing assertiveness of its Russian neighbor, but focuses most prominently on energy-related supply chains. India and the UAE note that cyber tools play a role in unwanted technology transfers, but do not explicitly tie the phenomenon to hybrid conflict. Another clear divergence can be observed in the intent actors prescribe to the use of hybrid tactics as an offensive tool. European actors (ESPAS, ECFR, Finland, and the Netherlands) universally perceive the offensive use of hybrid tactics as reflecting not only an increase in great power competition, but also a concentrated effort on behalf of perpetrating actors to erode their societies’ ability to react to foreign developments. China, Russia, and the US universally perceive the offensive use of hybrid threats as being geared predominantly towards fostering influence internationally, as well as being geared towards inflicting physical and/or economic damage on the domestic front.

CBRN weapons. CBRN weapons are explicitly identified as a threat by India, Israel, Japan, the US, and the UAE. Within this country sample, three of the Dutch observations regarding the threat posed by CBRN weapons are shared; namely: a) interstate competition’s role in incentivizing a race to the bottom vis-à-vis the development of strategic delivery vehicles, b) the likely destabilizing impact of technological developments, and c) the threats posed by nonstate actors. As it relates to interstate competition, the theme surrounding technological developments centers almost entirely around nuclear weapons. The threat of nonstate actors procuring and deploying chemical, biological, and radiological weapons is also commonly cited. Japan and the UAE preoccupy themselves most prominently with chemical and biological weapons, contending that new technologies – and nonstate actors’ access to information and/or blueprints over the internet – has significantly reduced the threshold to access.

Terrorism. Dutch perceptions regarding terrorism are widely shared by the actors included in this study. Australia, China, Finland, India, Israel, Japan, Russia, Singapore, the UAE and the US all afford a central position to terrorism. In a marked deviation from the Dutch nonstate-centric perspective, China, India, Israel, Russia, the UAE and the US identify terrorism as a phenomenon that is at least partially dependent on state support, thus overtly linking it to hybrid warfare and foreign interference. Whereas the Netherlands identifies right-wing extremism as being generally less impactful than its Islamist counterpart, ESPAS, MSC, and the US present right-wing extremism as posing a threat which equals (or even surpasses) the threat posed by Islamic extremism.

International Order

The actors included within this study identify the intensification of interstate competition and technological developments as factors which are driving developments in and shaping the perceived relevance of the international order. Though they universally identify the international order as eroding, perceptions regarding its nature are split between normatively, legalistically, and power-based views between “status quo,” “anti-status quo,” and “bystander” states respectively. Status quo states – Australia, Finland, Japan, Peru, the US, and the Netherlands –perceive the maintenance of the rules-based international order as a priority. These countries universally identify a combination of interstate competition within the military, economic, and (to a lesser degree) diplomatic domains, combined with the erosion of international adherence to democracy, as undermining it. The anti-status quo states China and Russia also posit that the existing international order has come under siege as a result of interstate competition, pointing to the US’ infringements on international agreements as evidence of its continuing decline. Finally, bystander states such as India, the UAE, and – to a lesser degree – Singapore, all outline the notion that an international power shift towards the Asia-Pacific region will require forging new partnerships in the near future, a sentiment which is shared by China and Russia.

Outside of the effects of international competition, several actors identify new technologies as driving a paradigm shift in the nature of the international system. India, Japan, Peru, the UAE and the US identify the dangers current technologies pose to democracy and the role they are playing in eroding support for the rules-based order even within its most committed defenders, as well as in empowering malicious nonstate actors to overcome asymmetries in conventional capabilities and to operate without the bounds of the rules-based order. These countries also observe that the advent of new technologies, the inequality of their distribution, and their concentration within private-sector actors, is likely to result in a diffusion of power away from states and in the emergence of entirely new governance models.

Omitted or Potentially Underappreciated Threats

Key threats which the Netherlands did not identify in the two high level security documents analyzed are advances in biotechnologies and climate change, both widely identified by the actors included within this study. CSIS, Japan, Russia, Singapore, the US, the WEF, and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETHZ) touch on the potentially destabilizing effects of advances in biotechnology, pointing towards nonstate actors’ ability to weaponize dual-use technologies such as CRISPR-CAS9 to stage lethal attacks. Climate change and environmental threats are identified as a threat category by Australia, CSIS, ECFR, ESPAS, ETHZ, Finland, India, Japan, Peru, Russia, the UAE, the US, and WEF. These threats are generally linked to several other threats, such as migration flows, increases in the initiation rate of intrastate conflicts, physical and environmental safety (wildfires, flash floods, loss of biodiversity, etc.), and political polarization. Additional other threats include the militarization of space, proxy warfare, energy security, demographic trends, and identity and/or nationality-based crises which are afforded more attention in other actors’ security perceptions.

Potential Opportunities

Threats clearly constitute the overwhelming focus of most of the analyzed documents. Even so, some hints of opportunities can be detected within this study’s actor sample. We would qualify most of these as ‘silver linings in the clouds’: negative developments that could possibly trigger some positive outcomes. China, ESPAS, ECFR, and Finland argue that the existential crises facing the world today (rampant Euroscepticism, climate change, great power competition, etc.) offer room for the radical restructuring of existing institutions and/or interstate relations. A trend can also be observed in the perception that regional institutions are better able to address localized problems than international organizations. China, ESPAS, ECFR, Finland, India, Israel, and Russia identify regional cooperation as an opportunity, pointing towards organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), or the European Union (EU) as examples of successful regional governance models. Finally, there exists a widespread adherence to the notion that the disruptive effects of new technologies are at least partially offset by their potential opportunities. Australia, ESPAS, India, and the US associate modern technologies with opportunities, positing that their development will facilitate the development of increasingly robust public services, increase economic output, and contribute to the mitigation of negative externalities associated with income inequality.

Disconnects and Potential Takeaways

A high-level analysis of the previously outlined trends allows for the drawing of several conclusions.

First, the six central threat categories in the Dutch GBVS align with those of its allies and states with which it entertains friendly relations, with some caveats. Finland, Israel, Japan, and the US identify and prioritize terrorism, IMC, CBRN weapons, and hybrid conflict as key threats, but often with subtly different accents. For example, Israel understands terrorism as a product of state support and regional competition rather than as a product of inequality and nonstate agency. The US views IMC and the proliferation of CBRN weapons not as a threat to its territorial sovereignty or to the rules-based international order, but as an indicator of other states’ efforts to undermine what it perceives as its military pre-eminence. Finland adheres to the Dutch view that the emergence of new technologies increases the threat posed by hybrid influence campaigns, but explicitly ties the negative impact of these campaigns to existing divides within society. The US identifies both new technologies (deepfakes, AI, etc.) and divides within society, but views the former as far more problematic than the latter.

Second, an analysis of omitted or potentially underappreciated trends shows that many of the threats identified by the Netherlands – and terrorism most prominently – are understood by other actors as being intrinsically linked to “intangible” phenomena such as international inequality or the proliferation of simmering discontent including on online platforms. The Dutch explicitly formulated views of these threats tend to be almost universally “tangible”. The risk of terrorist attacks is, for example, perceived as increasing not as a result of inequality or state fragility brought on by climate change, but by ISIS’ material defeat, targeted radicalization efforts on the part of terrorist recruiters, and (to a lesser degree) the openness of European borders.

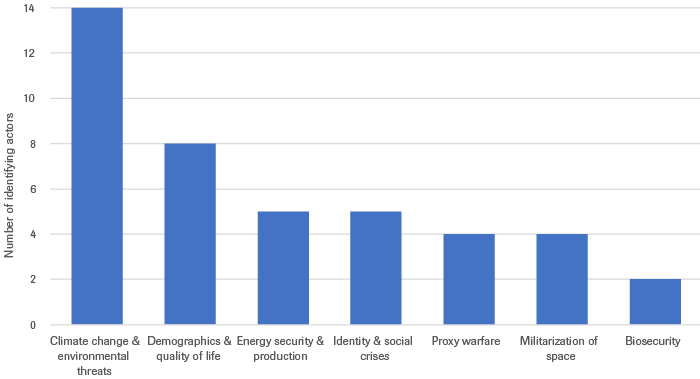

Third, several other threats were identified which potentially warrant explicit incorporation into future iterations of the Dutch threat perception framework. Key among these are climate change & environmental threats, demographics & quality of life, energy security & production, and identity & social crises, which are identified 14, 8, 5, and 5 times respectively. With the exception of energy security & production, these threats can universally be understood as “intangible” phenomena which cross-cut or are fundamental to the threats identified within the GBVS.

Fourth, very different perceptions exist of the current international order and the benefits actors derive from it. There are significant disconnects between status quo, anti-status quo, and bystander states. Actors in the status quo camp (Australia, Finland, the Netherlands, Japan, the US, etc.) universally point the finger at either China or Russia, arguing that these countries are engaged in a systematic effort to undermine the existing world order. On the other side of the spectrum, China and Russia point towards the status quo countries – and NATO and the US specifically – undermining the international order. Bystander states universally outline that international power shifts are likely to define the nature of the international order going forward. All camps perceive the existing international order as facing erosion. Interestingly, there are fundamental differences in the understanding of what constitutes the international order. More specifically, status quo actors can generally view it as a normative construct, anti-status quo states as a legal construct, and bystander states as a power construct. It is also important to note that, although the international order is touched on in some way or another by all actors in this study, it is only identified as a policy priority in Europe and the Netherlands.

Fifth, with the exception of the CBRN weapons threat, virtually no actor views developments pertaining to the six threats identified within the GBVS as particularly worrisome in terms of their potential impact on the rules-based international order. Australia and Japan both place high stock in the rules-based international order, but view its continued existence more through the lens of the continued provision of a security guarantee on the part of the US security than through the lens of the inherent benefits associated with the continued integrity of a framework which governs – and lends “civility” to – interactions between states. Only China and Russia share the Dutch and/or EU views on the inherent importance of an international order. However, these countries advocate for a significantly different international order than the one which is prioritized by the Netherlands and/or the EU.

Finally, opportunities emerge as a generally underappreciated aspect of threat perception frameworks across identified actors. Threats are clearly the overwhelming focus of most of the analyzed documents. The three high-level opportunities identified within this study – existential crises, regional institutions, and new technologies – can be understood as ‘silver linings in the clouds’ rather than as genuine ‘patches of blue sky’. Many stakeholders, from policymakers to politicians and policy analysts, seem to continue to think that defense and security efforts should self-evidently be tied to the (downside) risks that need to be attenuated or defended against. By doing so they ignore the many positive developments that may deserve more stimulation not merely from an altruistic, humanitarian or even self-serving financial-economic points of view, but also from a purely hard-noised defense and security perspective.

Introduction

A state’s threat perception framework can be impacted by an almost endless list of potential factors, both tangible (actual) and intangible (psychological).[2] Many different factors make up the process through which nations perceive certain threats as important, as well as the nation’s understanding and prioritization of these threats. Think, for example, of the nature of a country’s political system, the system’s interaction with socio-cultural factors and/or preconceptions, geographic proximity to danger, international aspirations and grand strategy.

The impact of these factors on countries’ threat perceptions needs not be ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ per se. The perception that terrorism constitutes a more immediate threat than the threat posed by interstate military competition (IMC) largely comes down to proximity, something which Finland for example has addressed through the notion of ‘psychological resilience’.[3] Similarly, a social-media-focused understanding of radicalization may derive from the observation that the majority of domestic foreign fighters were radicalized online.[4]

Regardless of whether a state’s threat perception framework is influenced by actual or by psychological factors, the very fact that such factors exercise demonstrable influence over state behavior is of relevance to the Netherlands. Outside of the obvious benefits associated with gaining deeper insights into allies’ and adversaries’ thinking about national security, there is also the potential for the Netherlands to gauge its own preconceptions.

This study aims to facilitate this gauging process by providing policymakers with insights into the security risks and opportunities identified by our allies and adversaries. In concrete terms, the study sets out to address the following research questions:

We have analyzed 38 individual post-2016 documents sourced from eleven countries and six think tanks and IGOs. Each country’s security perspective is analyzed based on two documents, one published by state institutions and one published by a locally based think tank. The results from these analyses are aggregated within a standard rubric to synthesize an overview of its threat perception framework. IGOs are analyzed by the same rubric, using a single recently published document, most often an annual report and/or comprehensive study. In addition, we explored trends in actors’ strategic foresight activities with the goal of extracting best practices for use in future iterations of the Strategic Monitor.

The identification of the abovementioned trends is of immediate relevance to the Netherlands. IMC, cyberconflict, hybrid and economic conflict, CBRN weapons, and terrorism all constitute cross-border, multifaceted phenomena. Terrorism is a threat that can take on different forms and can represent various political goals. It can also be widely associated with new technologies, which facilitate radicalization processes and may increase scale or effectiveness of terrorist acts. Conflict in cyberspace is a developing trend that will require extensive cooperation between governments and the private sector. The threats posed by modern-day IMC and by the subsequent modernization of key states’ nuclear arsenals are insurmountable by the Netherlands alone, and cannot be addressed without a coordinated international response. Hybrid tactics and states’ use thereof constitute a rising trend, which appears to point towards states’ disdain for the rules-based international order as a whole.

The exploration of other actors’ perceptions of the importance, utility, and longevity of the rules-based international order, as the Netherlands presents this order as constituting the backbone of its national security. The same applies to this study’s exploration of threats not afforded central positions within the Dutch threat perception framework. While the identification of true blind spots requires a thorough analysis of identified threats’ applicability to the Netherlands, the factually compiled list of omitted and potentially underappreciated threats could well serve as the basis for future discussions vis-à-vis the comprehensiveness (and appropriateness) of Dutch national security priorities. Finally, this study’s systematic outlining of opportunities aims to provide policymakers with concrete and actionable insights into potential courses of action identified by other actors.

This report is structured as follows. Chapter 1 offers an explanation of the research methodology. Chapter 2 lays out an in-depth analysis of similarities and differences in the Dutch perception of IMC, conflict in cyberspace, hybrid conflict and economic security, CBRN weapons, and terrorism relative to other actors. Subsequent chapters cover included actors’ attitudes towards the rules-based international order (Chapter 3), omitted and potentially underappreciated threats within the Dutch threat perception framework (Chapter 4), and identified opportunities (Chapter 5). The concluding chapter provides an overview of the most striking disconnects and lessons learned.

Methodology and Challenges

This study sets out to extract insights pertaining to a) differences between other actors’ perceptions of threats and those identified within the Dutch GBVS; b) actors’ perceptions of trends unfolding within the rules-based international (liberal) order; c) omitted and potentially underappreciated threats within the Dutch threat perception framework; and d) potential opportunities. The study’s research design consists of data collection and data analysis phases, outlined below.

Data Collection

In order to provide as comprehensive an overview of other actors’ security perceptions as possible, a list of eleven countries was made. Aside from the world’s great powers (China, the US, and Russia) – the security perceptions of which were viewed as being of particular importance to this study’s international order section – an effort was made to include countries from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) (the United Arab Emirates and Israel), Oceania and Pacific (Australia), Asian (India, Japan, Singapore), Latin American (Peru), and European (Finland) regions. The countries included in this study meet several criteria outside of the previously outlined regional comprehensiveness requirement. Chief among these are a) the publication of a relevant national security document no earlier than 2016;[5] and b) the aforementioned document’s availability in the English language.[6] Taken together, these requirements unfortunately resulted in the omission of Africa. To facilitate an analysis of other countries’ strategic foresight activities, countries were further selected on the basis of whether or not a reputable think tank boasting comprehensive security assessments (read: similar to the Dutch Strategic Monitor) operated from within their borders. A list of six reputable think tanks and/or international governmental organizations (IGOs) were additionally selected on the basis of expert opinion.

The application of the aforementioned criteria led to the identification of eleven countries and six IGOs, whittled down from a longlist of around forty actors, outlined in Table 1 and Table 2.

| Country |

Publication (public) |

Year |

Publication (private) |

Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia |

2016 |

North of 26 degrees south and the security of Australia: views from The Strategist |

2019 |

|

| The US |

2019 |

2017 |

||

| China |

2019 |

2019 |

||

| Russia |

2015 |

Theses on Russia's Foreign Policy and Global Positioning (2017-2024) |

2017 |

|

| Israel |

2015 |

Israeli National Security: A New Strategy for an Era of Change |

2018 |

|

| India |

2018 |

2016 |

||

| Japan |

2018 |

A New Security Strategy for Addressing the Challenges in the Turbulent International Order |

2018 |

|

| Finland |

2019 |

2019 |

||

| Singapore |

N/A |

N/A |

2019 |

|

| The UAE |

2017 |

United Arab Emirates Society in the Twenty-first Century: Issues and Challenges in a Changing World |

2018 |

|

| Peru |

2019 |

2016 |

| Institution |

Publication |

Year |

|---|---|---|

| Munich Security Conference |

2019 |

|

| World Economic Forum |

2019 |

|

| Zurich ETH |

2019 |

|

| European Council on Foreign Relations |

2019 |

|

| Center for Strategic and International Studies |

2015 |

|

| ESPAS |

2019 |

Data Analysis

Data was analyzed on the basis of a standardized rubric, outlined in Figure 1 below. For the purposes of this study, ‘unofficial’ (think tank-published) documents were used to supplement and ‘deepen’ the analysis of findings derived from government-published national security strategies. This is because government-published national security studies were frequently found to be short and to the point, offering little in the way of underlying threat perceptions and/or causality understanding. The final country case study rubrics thus constitute an aggregation of nationally and think-tank published documents.

Metadata

What year was the security document(s) published?

What actors were involved in the publication of the analyzed document?

Authors

Published by: public vs. private

Threats

What threats are identified?

How severe is the threat’s impact estimated to be (and why)? If applicable, what causality mechanism renders this threat particularly impactful from the analyzed countries’ perspective?

What driving factors are identified as contributing to the threat’s manifestation?

If applicable, what policy options are outlined for mitigating the threat’s manifestation?

Opportunities

What opportunities are identified?

How beneficial is the opportunities’ impact estimated to be (and why)? If applicable, what causality mechanism renders this opportunity particularly impactful from the analyzed countries’ perspective?

What driving factors are identified as contributing to the opportunity’s manifestation?

If applicable, what policy options are outlined for realizing the opportunity’s potential?

Are opportunities afforded a central position within the document?

International order / position of the Netherlands

Does the exercise analyze likely developments in the international order?

What developments does the analyzed study foresee as presenting in the international order?

Are these developments tied specifically to threats (i.e.: a more influential China is associated with a threat from the Australian perspective), or is this exercise more ‘neutral’ and trend driven?

How is the ‘international order’ conceptualized? (read: does the study view and/or measure the international order on the basis of a wide range of domains – if so, which domains – or on the basis of something else?)

Are the Netherlands or the EU and/or Europe specifically listed within the study? If so, within what context?

Systematic application of this rubric was problematized by several factors, many of which had methodological implications:

Threats. While all actors identified threats within both public and private sector-sourced publications, some discrepancies were observed in how different actors identified the same threat. For ease of analysis and in line with this study’s overarching goal to identify how different actors’ perceptions of the same threats differ, threats were grouped together when analysts understood them as describing roughly the same phenomenon. This resulted in the elimination of approximately thirty ‘redundant’ threat monikers. The final threat longlist includes 31 threats (see Table 8), which have been clustered into eight threat categories on the basis of shared themes and impact areas.

Opportunities. Opportunities were not widely identified by the actors included in this study, with instances of explicit, opportunity-oriented chapters being few and far between. As a result, the opportunities presented in Chapter 5 are more often than not inferred from policy recommendations or threat descriptions instead. For example, the opportunities presented in the US case study are inferred from a list of success factors which the country’s National Security Council (NSC) associates with potential future governance models. Chapter 5 on Opportunities further aggregates the approximately twenty distinct opportunities identified throughout this study’s case studies into three high-level categories: crisis as an opportunity, regional cooperation, and new technologies.

A note on strategic foresight and the methods used

This study was initially intended to map other countries’ efforts at strategic foresight and their methods, in addition to providing insights into biases, omissions, and potentially underappreciated threats in the Netherlands’ threat perception.

The difficulties associated with mapping out the aforementioned methods became evident at an early point in the study, not least because a) country-affiliated strategic foresight exercises comparable to the Strategic Monitor are few and far between, and b) the methods utilized towards the publication of such reports are frequently unclearly documented. Differences in the exact research questions, the scope and focus of the studies, and approach further complicate a comparative analysis of strategic foresight methodologies.

The ESPAS, Finland, Peru, Singapore and the US constitute the only countries and organizations included within this study’s country sample that conduct comprehensive strategic foresight exercises. These utilize expert-based methodologies in the synthesis of their reports.

For example, the US National Intelligence Council utilizes the following methodology for operationalizing trends and methodologies. The applied method is characterized by the following elements:

Threats

Collectively, the Dutch security documents within the context of this analysis identify a total of fourteen (14) unique threats,[7] namely: terrorism; conflict in cyberspace; interstate military competition (IMC); CBRN weapons; foreign interference and economic security; acceleration of technological developments and hybrid conflict; erosion of multilateral institutions; threats to vital economic processes; irregular migration; polarization and threats to social cohesion; threats to vital infrastructure; infectious diseases; natural disasters; criminal activities; and tensions within Europe. The available documents tend to prioritize ‘traditional’ threats by virtue of a) the likelihood that they will manifest, and b) their likely impact.

This calculus results in the prioritization of IMC, conflict in cyberspace, hybrid conflict and economic security, CBRN weapons, and terrorism using the six dominant threat themes in the GBVS.[8] The hybrid conflict and economic security threat category is split into elements relating to unwanted foreign interference and threats to vital economic security in the GBVS, but which (due to their clustering together under the hybrid moniker in the NSS) are combined within the context of this study.[9] These threats are almost universally shared by the actors analyzed within this study. Differences in how these threats are perceived allow for the formulation of the following (threat-specific) takeaways.

Interstate Military Competition

Both the GBVS and the NSS caution that the threat of the Netherlands becoming embroiled in or needing to contend with conventional, interstate violence is on the uptick. The Netherlands’ perception of this uptick derives broadly speaking from a combination of regional, structural, and institutional factors. At the regional level, the GBVS and the NSS both outline national instability (see Ukraine, Yemen, etc.) within the European near abroad as creating conditions conducive to outbreaks of intrastate conflict.[10] In these cases, the likely spillover of these conflicts into Europe itself is associated with an increase in the risk of conventional conflict. Structural factors relate almost universally to the Dutch identification of interstate competition as a source of international instability which incentivizes states not only to engage in ‘race-to-the-bottom’ arms races, but also to engage in activities that undermine international normative and legal frameworks, thus lowering the barriers to the use of conventional force.[11] Thus, the increased military assertiveness is portrayed as a factor likely to give rise to military conflict (Table 3).[12]

Dutch perceptions that the threat of military engagements is on the uptick are further increased as a result of institutional factors. Specifically, the Netherlands’ membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) – particularly when combined with the US’ engagement in interstate competition – increases the likelihood of an Article 5 activation.[13] The Netherlands also notes that international interconnectedness empowers ill-intentioned actors to utilize military means (whether conventional, cyber, or otherwise) to erode a country’s physical and/or economic security through the disruption of critical supply chains, among others (Table 3).[14]

| High-Level Impact |

Manifestation |

Contributing factor(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Increased risk of military confrontation |

Interstate competition |

Increase in militarily assertive rhetoric |

| Increases in military posturing & expenditure |

||

| International race-to-the-bottom in R&D |

||

| Erosion of the rules-based international order |

Increase in militarily assertive rhetoric |

|

| Increases in military posturing & expenditure |

||

| International race to the bottom in R&D |

||

| Spillover conflicts |

Instability in the European near abroad |

|

| Increased vulnerability to disruptions through military means |

Disruptions of critical supply chains |

Interstate competition |

| Increased level of international connectedness |

The threat of IMC is identified as a threat by Finland, India, Israel, Japan, Russia, the US, and China. The ESPAS and MSC additionally identify IMC as being on the uptick.[15] Among these actors, the most commonly held view is that an increase in interstate competition increases the risk of a military confrontation, though the focus of this perception differs between actors.

China, Japan, Russia, and the US, all place an emphasis on their competitors’ efforts at military modernization, pointing towards increasing defense budgets and the unveiling of cutting-edge (conventional) weapons systems as signs of aggression.[16] In the Chinese case, modernization is attributed largely to technologies it understands as drivers of a new “technological and industrial revolution,”[17] including “artificial intelligence (AI), quantum information, big data, cloud computing and the internet of things.”[18] China also explicitly references terms such as “informationized warfare”[19] thus further confirming the notion that its perceptions of IMC center around military modernization and/or transformation through technology. This sentiment is echoed by Russia, which posits that “militarization and arms-race processes are developing in regions adjacent to Russia” and that “the role of force as a factor in international relations is not declining.”[20] Japan’s threat perception is most predominantly concerned with developments in China and Russia. In the case of China, Japan views the country’s efforts at strengthening “its asymmetrical military capabilities to prevent military activities by other countries in the region”[21] as particularly concerning. In the case of Russia, Japan’s focus is on the overlap of the Kremlin’s and Japanese periphery (Chishima Islands). In a further alignment with the Netherlands, Russia and Japan also both identify IMC as a threat to the existing rules-based international order, with Russia positing that “the aspiration to build up and modernize offensive weaponry and develop and deploy new types of weaponry is weakening the system of global security and also the system of treaties and agreements in the arms control sphere,”[22] and Japan viewing the assertions that accompany Chinese efforts at modernization as being “incompatible with the existing order of international law.”[23]

China, the US, and (to a lesser extent) the Netherlands view the negative impacts of IMC as manifesting most prominently at the international level. However, Finland, India, Israel, and Japan view IMC through the lens of either a) the regional dynamics on which it is based, or b) the regional insecurity it is likely to exacerbate. In the Japanese case, Tokyo’s focus on the threats associated with modernization can be readily attributed to its interests in the South China Sea. Finland emphasizes the worrisome nature of Russian incursions into Ukraine, as well as Russia’s development of sophisticated Anti-Access/Area-Denial (A2AD) capabilities.[24] India points towards competing territorial claims with both China and Pakistan as a factor informing its concerns over the nature of those countries’ ongoing military investments. It is important to note that, though most actors’ regional focus means that attention for the notion that instability in the European periphery increases the risk of a spillover conflict is widespread, only the ESPAS explicitly sets out to identify drivers of the aforementioned instability. Most notably, the ESPAS identifies regional and/or local inequalities, particularly in combination with demographic trends – such as the presence of a youthful demographic combined and the social inequalities this may entail in the North African region – as the foremost driver of instability in the European periphery.[25]

Dutch concerns regarding the triggering of NATO’s Article 5 and instability in the European periphery are most clearly shared by Finland. Its views on flow security – the notion that the country is vulnerable to the disruptions of critical supply chains – is not explicitly echoed by any actors included in this analysis.[26]

Conflict in Cyberspace

Cyber threats are afforded a central position within Dutch security planning, in no small part because the country’s high degree of digitization. The Netherlands’ understanding of cyber threats places a heavy emphasis on cyberattacks as a phenomenon. The fear is that the country’s growing dependence on cyber-based infrastructure (think of interfacing constructs such as DigID) renders its society vulnerable to large-scale disruptions originating in cyberspace.[27] From the Dutch perspective, the threat posed by cyberattacks is exacerbated by several factors, namely a) the country’s high degree of systems’ interdependence; b) the relatively low costs associated with conducting a cyberattack; and c) perceived inadequacies in the degree to which the country has engaged in cyber-resilience-building. The Netherlands views these factors together as lowering the threshold of operations for state and nonstate actors alike, thus rendering the country vulnerable not only to the negative (physical) externalities associated with attacks on critical infrastructure, but also to economic espionage and to disruptions of social and political integrity through influence campaigns (Table 4).[28]

| High-level impact |

Manifestations |

Contributing factor(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Disruptions of critical infrastructures |

Sabotage, espionage, crime |

Growing dependence of citizens and infrastructures on cyber domain and innovation |

| Lowering threshold of attack |

||

| Lagging resilience (systemic) |

||

| Disruptions of social and political integrity |

Influencing, espionage, sabotage |

Lagging resilience (systemic) |

| Lowering threshold of attack |

||

| Growing dependence on cyber domain and uncontrolled innovation |

||

| Growing involvement of state-sponsored actors |

||

| Societal collapse |

Chain collapse of vital systems |

Interdependence of infrastructures |

| Lagging resilience (systemic) |

Dutch perceptions regarding the threats posed by conflict in cyberspace are widely shared by actors included in this analysis. The Australia, Finland, Israel, Japan, Singapore, the UAE, and the US, all explicitly elaborate on the threats posed by malicious actors’ activities in cyberspace, as do the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), ESPAS, Munich Security Conference (MSC), and World Economic Forum (WEF). The Netherlands’ perception that this conflict in cyberspace poses a threat to critical infrastructure is widely shared, [29] as is the notion that the potential impact of this phenomenon is amplified by the cyber domain’s penetration of virtually all spheres of life. Simultaneously, several states adhere to a broader, less cyberattack-centric understanding of threats in cyberspace, and often view it in a significantly broader context than the Netherlands, touching on a) the likely impact of new technologies and/or innovation; b) cyber technologies’ likely impact on the military balance of power; and c) cyber technologies’ likely impact on the international balance of power writ large.

Starting with similarities between the threat perception framework adhered to by the Netherlands and the threat perception framework adhered to by other actors, these are a) the widely shared view that conflict in cyberspace poses a threat to critical infrastructure, and b) the idea that the potential impact of this phenomenon is amplified by the cyber domain’s penetration of virtually all spheres of life. Australia, the CSIS, Finland, Israel, Japan, the UAE, the US and the WEF, all emphasize systems’ interdependencies in critical infrastructure as a factor heightening their societies’ vulnerability to cyberattacks. The UAE notes that society is becoming increasingly digitized, positing that by 2020 this will result in an exponential increase in the number of threat vectors.[30] Japan points out that “cyberattacks on telecommunication networks of a government and military forces, or on critical infrastructure could have a serious effect” on national security.[31] The WEF notes that “digitalization and the Internet of Things have deepened connectivity across the world, increasing the potential for malicious actors to mount online attacks and amplifying their potential damage.”[32] Australia identified cyber threats as having impacts well beyond defense, arguing that they have the potential to “attack other Australian government agencies, all sectors of Australia’s economy and critical infrastructure and, in the case of state actors, conduct state-based espionage including against Australian defense industry.”[33] A large number of these actors – namely: Israel, Japan, the UAE, the US, and the WEF, – also subscribe to the notion that the cyber domain penetrates virtually all spheres of life. In some actor cases, this results in the designation of ‘non-traditional’ forms of critical infrastructure. As an example, Japan describes the cyber domain’s widespread penetration as impacting not only central authorities’ ability to interfere with citizens’ behavior, but also with the military and with businesses.[34] A similar sentiment is echoed by the WEF, which identifies widespread digitization as resulting in the proliferation of financial crime, intelligence gathering, and illicit data collection. In each of these cases, newly identified vulnerabilities or recorded malicious use cases and/or practices prompt new thinking regarding the definition of critical infrastructure.[35]

Moving on to notable differences in how conflict in cyberspace is perceived as a threat and/or in how elements of this threat are prioritized, these are discussed in the topics of a) the likely impact of new technologies and/or innovation; b) cyber technologies’ likely impact on the military balance of power; and c) cyber technologies’ likely impact on the international balance of power writ large. Starting with the likely impact of new technologies and/or innovation, this threat perception is most prominently championed by the CSIS, ESPAS, Japan, the UAE and the WEF, and is endemic of a threat perspective in which threats associated with the cyber domain derive from its likely future role in interstate competition. This view constitutes a significant departure from the Dutch perspective that cyber threats almost exclusively take the form of cyberattacks. The ESPAS relates this phenomenon most concretely to polity, contending that innovations relating to the cyber domain, and states’ use thereof, are set to contribute to the proliferation of authoritarian governance models. The CSIS argues that the speed at which technologies such as AI are being developed and innovated on problematizes the process of ascertaining “which characteristics and capabilities will be militarily decisive,”[36] thus lamenting a likely race to the bottom within the cyber domain.

Not unrelated to the previously outlined departure from the Dutch perception of conflict in cyberspace as a threat to national security, several actors lament cyber technologies’ likely impact on the military balance of power and (by extension) on the international balance of power writ large. In a twist on the Netherlands’ notion that the cyber domain may be weaponized by malevolent actors wishing to the undermine the country’s social fabric, Singapore contends that the economic inequalities it propagates are likely to achieve a similar effect by creating a cyber aristocracy,[37] with the envisioned outcomes being the undermining of social stability, an increase in the dysfunctionality of democracy, and a further diffusion of power to non-state actors.[38] China,[39] Japan, the MSC, Singapore, the UAE and the US also outline the cyber domain’s likely impact on interstate competition, placing specific emphasis on the domain’s military applications. Views regarding the cyber domain’s likely impact on military affairs differ between actors. Australia, the CSIS, Israel, Singapore, the UAE and the US place an emphasis on cyber capabilities’ role in empowering state and non-state actors to overcome adversaries’ conventional advantages, while China, Russia, MSC, and WEF place a stronger emphasis on the ‘race to the bottom’, which is evident from developments in, e.g., autonomous warfare.

Hybrid Conflict and Economic Security

Within the context of this study, the GBVS’ unwanted foreign influences and economic security-related threats are compounded under the hybrid warfare moniker. This is because these threats do not explicitly recur in the national security strategy, and fall – in many other actors’ security documents – under the hybrid warfare moniker.

Hybrid threats are afforded a central position within the Netherlands’ threat perception. The GBVS and the NSS each identify a wide range of threats and negative externalities which are commonly understood as under the umbrella of the ‘hybrid threats’ moniker.[40] In the case of the Nationaal Coordinator Terrorismebestrijding en Veiligheid’s (NCTV) 2019 NSS, the centrality of subjects such as unwanted foreign influences, polarization and threats to social cohesion, and (though to a lesser extent) cyber threats and threats to critical infrastructure and to private-sector IP protections all contribute to the hybrid threat category’s recurrence on this list.[41] These sentiments are by-and-large echoed in the GBVS, which also places an emphasis on the threat external influences may pose to Dutch social cohesion and democratic process.[42] The GBVS additionally identifies modern technologies as well as the implications of hybrid tools being employed against other countries as factors contributing to the heightening of the hybrid category’s overall threat level.[43] A recurring theme within the Dutch understanding of hybrid threats is the view that the openness of Dutch society renders the country particularly vulnerable to disinformation campaigns (Table 5).

| High-level impact |

Manifestations |

Contributing factor(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Impacts on internal fabric (societal security) |

External influence campaigns |

Increased degree of global interconnectedness |

| Modern technologies |

||

| Disinformation |

Modern technologies |

|

| Openness of Dutch society |

||

| Threats to physical and economic security |

Disruption of critical infrastructure |

Cyber domain |

| Threats to security environment (external) |

Erosion of liberal norms in the European periphery |

Increased degree of global connectedness |

| Modern technologies |

Hybrid threats are identified by virtually all actors included in this study, although the terminology used to refer to them varies.[44] Some actors (e.g. Israel, Russia, and the US) identify threats such as ‘influence operations’, but do not combine them under a hybrid umbrella. Others refer to ‘hybrid threats’ or to ‘gray zone operations’. This study aggregates these framing differences for the sake of readability. Convergences with the Netherlands’ perception take the form of a) the notion that influence operations constitute an important element of hybrid campaigns; and b) the notion that new technologies play a facilitating role. The consensus regarding economic tools’ place in hybrid toolkits and the threats that the use of these tools poses differs between actors. Some align with the Dutch view that these are largely geared towards impacting economic security, while others subscribe to the notion that these tools are best understood as another kind of influence operation.

The vast majority of actors that identify hybrid tools and/or gray zone operations as a threat, acknowledge the phenomenon of unwanted foreign influences. The CSIS, the ECFR, ESPAS, Finland, the US, and the UAE, all touch on influence campaigns as a threat. Common within this subset of actors is a focus on a) new technologies, and b) vulnerabilities brought about by societal openness – both factors which the Netherlands outlines explicitly. This notwithstanding, actors’ definition of what constitutes an influence campaign differ somewhat. Though all actors view influence campaigns as being grounded at least partially in the spreading of misinformation, they vary in their perceptions of the structural factors that facilitate them. For example, the US views Russia’s social media efforts as being geared towards “aggravating social and racial tensions,”[45] meaning that the US perceives preexisting social and racial tensions as a factor facilitating and/or increasing the likely impact of influence operations. This perception is widely shared by the ECFR and the UAE, which respectively identify the presence of “sects and ethnic groups”[46] and “societal divisions” as a structural factor facilitating hybrid influence campaigns.[47] It is less clearly shared by Finland and the ESPAS, both of which view these campaigns less as being geared towards exacerbating and/or widening existing wedges, and more towards carving out new ones.

Another convergence with the Dutch perspective manifests under the guise of new technologies. Finland, the UAE, and the US align with the Netherlands’ view that the threat posed by modern influence campaigns is increased by the availability of technologies such as the internet, arguing that the openness of their societies – particularly when combined with the proliferation of social media and the widespread availability of AI-based technologies – constitutes a structural vulnerability within their civic processes. The framing of this structural shortcoming differs between actors, with the US positioning the use cases for new technology as the primary driver of increases in adversaries’ ability to intervene in its democratic processes.[48] Most notably, the US cites the disruptive potential of deepfakes, as well as cyber tools’ contributions to allowing foreign intelligence services to “collect intelligence, erode US democracy, and undermine US national policies and foreign relationships.”[49] Finland,[50] the UAE,[51] and (to a lesser degree) the Netherlands position new technologies as a factor which exacerbates the negative impact of existing fault lines within society.[52]

Moving on to state perceptions of economic tools, these exhibit a split between actors which view the use of economic tools as being geared towards supplementing and furthering the impact of influence operations, and actors which view the use of economic tools as being geared towards impacting economic security. The perception that these tools serve the purpose of facilitating influence campaigns is most prominently vocalized by Finland, which holds the view that “economic methods, such as financing, investments and trade, can also be used for pursuing influence and dependence that will later restrict the targeted state’s freedom of action.”[53] The ECFR, Finland, Japan, Russia, and the US note that the coercive use of economic tools constitutes an important part of hybrid conflict. Russia emerges as the only country within this subset to explicitly outline that it is developing “interrelated political, military, military-technical, diplomatic, economic, informational, and other measures.”[54] Finland identifies the disruption of critical supply chains as a threat deriving potentially from the increasing assertiveness of its Russian neighbor, arguing that these economic dependencies are likely to restrict its “freedom of movement in future.”[55] The ECFR outlines that “great powers, particularly China and the US, are increasingly using economic tools for geopolitical purposes, and have no qualms about doing so.”[56] Furthermore, Finland, Russia, the UAE and the US align with the Dutch perception that the cyber domain allows for the disruption of critical infrastructure, with Finland and the UAE in particular elaborating this attack vector’s role in hybrid coercion.[57] The clearest examples of actors whose views regarding hybrid threats’ impact on vital economic processes align with those held by the Netherlands can be observed in the China, US, and (to a lesser extent) the Israel Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS). China and the US each identify economic coercion as elements of their competitors’ hybrid toolkits. The US also ties activities within the cyber domain explicitly to state-supported espionage operations and to the theft of intellectual property, thus expanding on the scope of “vital processes” as defined by the Netherlands.

A clear divergence can be observed in the intent actors prescribe to the use of hybrid tactics as an offensive tool. European actors (ESPAS, the ECFR, Finland and the Netherlands) universally perceive the offensive use of hybrid tactics as reflecting not only an increase in great power competition, but also a concentrated effort on behalf of perpetrating actors to erode their societies’ ability to react to foreign developments. China, Russia, and the US perceive the offensive use of hybrid threats as being geared predominantly towards fostering influence internationally, as well as towards inflicting physical and/or economic and sometimes even societal damage. Concerns over hybrid tactics’ potential to inflict societal damage are expressed most prominently by Russia, which posits that “the intensifying confrontation in the global information arena caused by some countries' aspiration to utilize informational and communication technologies to achieve their geopolitical objectives, including by manipulating public awareness and falsifying history […].”[58] This perspective is shared by Israel and India, with the caveats that these countries’ focus is a) purely regional in nature, and b) centered around the use of proxy militias (read: not overly concerned with foreign influence campaigns as a phenomenon).

CBRN Weapons

The threat posed by chemical, biological, radioactive and nuclear (CBRN) weapons is identified within both the NSS and the GBVS. The NSS perceives the threat as deriving from a number of developments conducive to non-state actors’ procurement and use of weapons. The NSS frames these developments as relating almost universally to international developments, pointing towards (among others) the erosion of existing arms regimes and the facilitating nature of new technologies.[59] These sentiments are largely echoed in the GBVS, which similarly laments the erosion of international institutions, but which places a far heavier and/or more prominent emphasis on states as central actors.[60] Whereas the NSS outlines how new technologies and the erosion of the international order increase the risk of terrorist organizations and other non-state actors developing chemical, biological, or rudimentary radiological weapons, the GBVS emphasizes interstate competition’s role in incentivizing the modernization of nuclear arsenals and funding for R&D into AI and synthetic biology. Apart from being viewed as a threat to the Netherlands’ physical safety, these trends are viewed as undermining non-proliferation norms for CBRN weapons (Table 6).

| High-Level Impact |

Manifestation |

Contributing factor(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Threat of mass casualties caused by CBRN weapons |

State actor use of CBRN weapons |

Instability of arms control regimes |

| Interstate competition |

||

| Non-state actors’ procurement and/or use of CBRN weapons |

Instability of arms control regimes |

|

| Technological developments |

||

| Further destabilization of existing CBRN arms control regimes |

CBRN proliferation |

Changing nuclear doctrines |

| Modernization and expansion of CBRN arsenals |

Technological developments |

|

| Interstate competition |

CBRN weapons are explicitly identified as a threat by India, Israel, Japan, the UAE, and the US. Contrary to what was the case with the terrorism and conflict in cyberspace threat categories, all three of the Netherlands’ observations regarding the threat posed by CBRN weapons are widely shared by other actors in this sample, namely a) interstate competition’s role in incentivizing a race to the bottom, b) the likely destabilizing impact of technological developments, and c) the threats posed by non-state actors. The following paragraphs provide insights into identifying how actors’ specific takes on these themes differ from the views held by the Netherlands.

Dutch views regarding the role played by interstate competition are shared by Israel, Japan, the UAE, and the US. Similarities relating to the theme of interstate competition and CBRN weapons center almost universally around the notion that a renaissance in interstate competition has brought with it an increase in the threat of nuclear proliferation. Views regarding the threatening nature of IMC diverge between actors, with the Netherlands being most preoccupied with the likely repercussions for the rules-based international order, the US lamenting the strategic implications of competitors’ ongoing modernization programs, and Israel, Japan, and the UAE seeing IMC as a driver of nuclear proliferation and of regional instability and conflict. The US’ threat perception points out that several competitors are engaged in modernization programs centering around the development of strategic delivery vehicles capable of penetrating US missile defense systems,[61] thus gravitating towards a realpolitik, power balance-centric understanding of IMC’s impact on and interactions with the threat posed by CBRN weapons. Whereas the Netherlands preoccupies itself most predominantly with nuclear proliferation as a process that undermines the international rule of law, Israel, Japan, and the UAE universally observe nuclear proliferation in the context of its likely contribution to regional instability and conflict. Japan is predominantly concerned with North Korea, pointing out that its activities constitute “unprecedented, serious and imminent threats to the security of Japan.”[62] Israel focuses almost exclusively on Iran, noting that Tehran’s activities are likely geared towards erecting a “strategic umbrella for the regime in its endeavor to achieve influence and hegemony throughout the Middle East.”[63]

Moving on to the likely destabilizing impact of technological developments, these pertain to the development of advanced strategic delivery vehicles on the one hand, and to the perception that the threat of non-state actors procuring CBRN weapons is on the uptick on the other. Dutch understanding of new technologies for delivery vehicles largely focuses on implications for existing arms control regimes, as well as for the rules-based international order more generally. Other identifying actors generally do not consider this angle, choosing to focus instead on strategic implications (US) or on regional instability (Israel, Japan, and the UAE). Also of relevance is that whereas, as it relates to interstate competition, the theme surrounding technological developments centers almost entirely around nuclear weapons, technological developments’ interaction with the threat posed by non-state actors derives from the access it is likely to give them to chemical, biological, and radiological weapons. The Japanese perspective preoccupies itself most with chemical and biological weapons, contending that new technologies and their ease of accessibility have significantly reduced the threshold to access.[64] In a similar vein, the UAE identifies ‘do-it-yourself’ (DIY) methods of building Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMDs) – particularly when combined with access to information and reductions in the overall cost of procurement – as contributing to an increase in non-state actors’ ability to access chemical and biological weapons.[65] Radiological weapons are generally not touched upon, though the notion of terrorist organizations obtaining the materials necessary to build a dirty bomb are alluded to by Russia, deriving from its concerns relating to a lack of state oversight in the post-Soviet era and from perceived state sponsorship of terrorist organizations.[66]

Terrorism

Themes relating to terrorism are touched upon in both the GBVS and the NSS, albeit within slightly different contexts. The GBVS places an emphasis on terrorism as an external threat, associating it most prominently with migrant flows, instability, and state failure in the European periphery.[67] The NSS focuses more on internal threats posed by terrorism, and emphasizes radicalization processes, the threat posed by returning fighters, the problem of lone wolf terrorism, and terrorists’ ability to undermine the fabric of Dutch society.[68] Given the NSS’ annual publication cycle, the 2019 iteration of Dutch security thinking places a particular emphasis on the threat that fighters returning from conflicts in the Middle East pose to Dutch security, and how existing dynamics (incarceration, the internet, etc.) are likely to exacerbate the threat these individuals pose to Dutch society. Neither the NSS nor the GBVS place a strong emphasis on right-wing extremism as a terrorist threat, though the NSS does note identitarian extremism as a factor which contributes to anti-government sentiments and to the undermining of the Netherlands’ democratic process in general (Table 7).

The Netherlands also correlates terrorism with several structural factors, including global inequality and organized crime. These are respectively described as exacerbating individuals’ willingness to engage with radical ideologies (global inequality) and as facilitating terrorist activities through, for example, logistics and funding (organized crime).[69]

| High-level impact |

Manifestations |

Contributing factor(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Physical damage (internal) |

Terrorist attacks |

Proliferation and mobility of ideology |

| Socio-economic inequality |

||

| Crime–terror nexus |

||

| Undermining of democratic principles |

Expansion of political, anti-government extremism |

Growing ‘identarian’ sentiment and culturally defined divisions |

| Instability in the European vicinity |

Mobility of jihadists |

Military defeat of the physical caliphate in the Middle East |

| Socio-economic inequality |

Dutch perceptions regarding terrorism are widely shared by the actors included in this study, though several caveats apply. Australia, China, ESPAS, Finland, India, Israel, Japan, Singapore, Russia, the UAE, and the US, all identify and afford a central position to terrorism within their national security strategies.[70] These actors generally align with the Netherlands’ views regarding terrorism’s roots in Islamist extremism. The notion that terrorism poses a threat to physical and/or territorial integrity is also universally shared. However, perspectives diverge along a number of key fault lines. A pronounced trend can be observed in the perception that terrorism constitutes a threat that is first and foremost dependent on state support. Several actors place a pronounced emphasis on the threat posed by right-wing extremism, positing that its threat level supersedes its Islamic equivalent. A pronounced focus on the potentially transformative nature of new technologies is also prevalent.

Starting with similarities, these concern the notions that terrorism a) is rooted in Islamist extremism, and b) poses a threat to physical and/or territorial integrity. Australia, Finland, the UAE, and the US view terrorism as being primarily rooted in Islamist ideology. ESPAS posits that al-Qaeda’s strategic approach has been “validated” by ISIS’ defeat, arguing that the former’s resurgence is likely.[71] Singapore has taken specific steps to ensure that “the Muslim community remains integrated into the broader society,”[72] arguing that further efforts are needed to employ religious leaders towards the cause of condemning religious radicals. The UAE makes frequent references to ISIS.[73] The US continues to place a strong emphasis on the prevalence of global jihadist movements, though it does posit that these movements have experienced some “significant setbacks.”[74] The US also constitutes the clearest example of a country that explicitly states that terrorism poses a threat to physical and/or territorial integrity, in positing that “prominent jihadist ideologues and media platforms continue to call for and justify efforts to attack the US homeland.”[75]

Moving on to notable differences in how terrorism is perceived as a threat and/or in how elements of this threat are prioritized, these differences are mainly visible in the discussing the notions of terrorism being contingent upon state support, the prioritization of right-wing extremism over Islamist radicalization, and advances in technology. Starting with the notion that terrorism is contingent on state support, this is adhered to by China, India, Israel, Russia, the UAE, and the US. India identifies state-sponsored terrorism – more specifically, by Pakistan in Jammu and Kashmir – as the “foremost internal security challenge faced by the country.” [76] Israel identifies Hezbollah and Hamas as “substate organizations,”[77] though it also concedes that “organizations without links to a particular state or community” pose a threat as well.[78] The US associates state support for terrorism most prominently with Iran, positing that the country “almost certainly will continue to develop and maintain terrorist capabilities as an option to deter or retaliate against its perceived adversaries.”[79] In the cases of India, Israel, the UAE, and (to a lesser extent) the US, this politicization can be partially understood from within the context of these countries’ ongoing engagement with local and/or regional competition;[80] in others, it can be partially understood as a form of posturing.[81]

The identification of right-wing extremism as a threat of which the impact is equal to or even greater than Islamist extremism, constitutes another divergence from the Dutch perspective on terrorism. Whereas the Netherlands identifies right-wing extremism as being generally less impactful than its Islamist counterpart, the ESPAS and the US both present right-wing extremism as posing a threat which equals or even surpasses the threat posed by Islamic extremism. The ESPAS notes that, “while jihadist terrorist attacks dominate the news, they constitute only 16% of terrorist attacks; 67% of attacks were of a separatist nature, 12% left-wing and 6% right-wing.”[82] The ESPAS also ties home-grown terrorism to poor integration and inequality.[83] The US ties right-wing extremism to “ethno-supremacist and ultranationalist groups,” arguing that these groups are likely to “employ violent tactics” in efforts to stymie immigration.[84]

There is also increasing attention for the impact of new technologies, which are credited not only with offering pathways to radicalization, but also with transforming terrorists’ potential capabilities as a whole. Australia, the ESPAS, Japan, and the UAE, all afford social media (and the internet more generally) a central position within their understanding of radicalization – whether Islamist, right-wing, or otherwise. Dutch views regarding the proliferation of radical ideologies center almost entirely on Islamist ideologies, and (as a result) tend towards outlining dangers associated with ISIS’ material defeat, former fighters’ ability to utilize refugee flows to gain (re-)entry to Europe, and these individuals’ tendency to radicalize inmates during incarceration. The ESPAS notes that “all terrorist networks use the internet to recruit, exchange information, funds and knowledge.”[85] This sentiment is echoed by the UAE, which posits that “technology diffusion enables terrorists to develop their capacities, innovate, and act (recruit, secure financing, communicate, self-promote, attack, etc.) in an increasing number of areas.”[86] Japan ties the internet to “lone wolf” attacks, arguing that these individuals become “influenced by extremist ideology through information found on the Internet and elsewhere, without having any official relations with terrorist organizations.”[87] Several countries – Finland, Russia, the US, and the UAE most prevalently – also touch on new technologies as tools which bolster terrorist organizations’ abilities and/or lethality. In concrete terms, Finland places emphasis on the notion that terrorist organizations may develop the ability to conduct sophisticated cyberattacks, thus empowering them to cripple critical infrastructure.[88] Russia is more concerned with the prospect of terrorists obtaining CBRN weapons.[89] The US and the UAE are both relatively aligned with Finland’s perspective. The US places an emphasis on the cyber domain’s ability to empower terrorist organizations to “disclose compromising or personally identifiable information through cyber operations, […] to inspire and enable physical violence, […] and defacing websites or executing denial-of-service attacks against poorly protected networks.”[90] The UAE places a greater emphasis on the potentially destabilizing nature of DIY CBRN weapons, the availability of which, it argues, has been facilitated by the diffusion of advanced dual-use technologies.[91] The UAE posits that these make it “easier for a tyrant, terrorist, lunatic, or simply a curious student to create a doomsday virus or an organism that combines long latency with high virulence and mortality.”[92]

International Order

The actors included within this study largely identify the intensification of interstate competition and technological developments as factors that are driving developments in and shaping the perceived relevance of the international order. Differences in how these trends’ impact is perceived generally differ between ‘status quo,’ ‘anti-status quo’, and ‘bystander’ states, which can respectively be generalized as taking normative, legalistic, and power-centric views of the international order as a construct. The aforementioned disconnects in how actors perceive the essence of the existing international order helps to explain some of the opposing observations that emerge from the analysis presented below.

Starting with the rules-based, liberal world order’s relevance as perceived by the actors included within this study, the sample shows a (not unexpected) split between what can generally be understood as being pro- and anti-status quo actors. Australia,[93] Finland,[94] Japan,[95] Peru,[96] and the US all touch specifically on the rules-based international order’s relevance to facilitating interstate cooperation, mitigating the onset of interstate conflicts, and tackling cross-border challenges such as terrorism and climate change. Within this cluster of pro-status quo actors, views regarding the nature and drivers of the international order are not uniform. The US views the liberal international order as an extension of its global hegemony. The country acknowledges that active efforts (rather than military and/or economic power shifts) on the part of China and Russia have contributed to undermining “once well-established security norms”[97] and to these countries’ shaping of “global rules and standards to their benefit,”[98] with the explicit goal of counterbalancing US hegemony. Contrarily, Australia, Finland, Japan, and Peru universally acknowledge and, in many cases, explicitly refer to the notion of international power shifts within the military and economic domains as calling the future of the existing rules-based order into question. Though these actors tend to clearly formulate their preferences for the continued existence of the existing (US-led) international order,[99] several entities – Finland and the EU-based ESPAS in particular – associate its erosion with opportunities. Chief among these opportunities is the notion that the erosion of the US-led international order, a construct which has long served as a guarantor of European security, opens the door for a more concentrated push to achieve strategic independence on the EU’s behalf.[100] A key observation within the ‘status quo’ camp can be derived from the grounds on which the actors falling within it identify the intensification of interstate competition as being detrimental to the integrity of the international order. Most prominently, these actors’ lamenting of Russian and Chinese infringements vis-à-vis normative issues (read: democracy as an institution, human rights, etc.) speaks to their perception that the international order constitutes a structure which is primarily normative in nature.