Introduction

As geopolitical rivalry is regaining prominence and technology is advancing, states are more actively engaging in interstate military competition (IMC). This is evident in activities such as the ramping up of military investments in dual-use AI technologies and the growing militarization of space.[1] Even though instances of direct military confrontation remain limited, internationalized intrastate conflicts have grown in both their prevalence and intensity.[2] The adversity fostered by these dynamics, combined with the proliferation of new technologies, is placing considerable stress on the international order. This can clearly be seen in, for example, the erosion of existing arms control regimes, as well as in states’ use of proxy actors to circumvent regulations. This results in a significant increase in the threat posed by IMC to the Netherlands. In concrete terms, this threat may manifest in an increased chance of armed conflict on NATO’s territory. The threat level is further raised by the fact that IMC increasingly manifest itself in non-traditional forms, which are associated with a host of negative externalities and effects for economic security and societal cohesion.

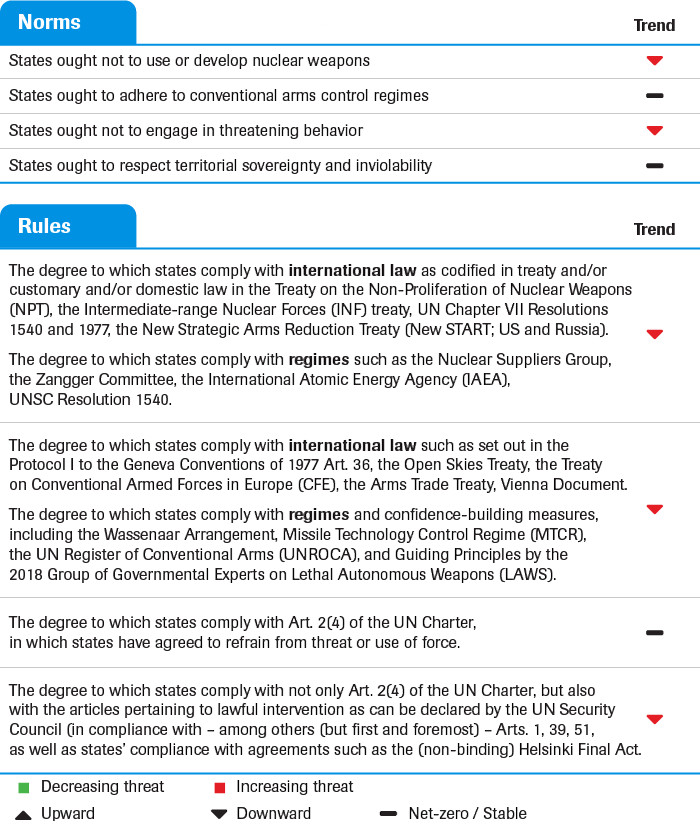

The Global Security Pulse (GSP) on IMC was published in February 2019. This research report examines the underlying quantitative and qualitative evidence presented in the GSP’s two trend tables. It covers trends in interstate military competition and international regime developments over the past ten years.[3] It builds on the previously published Strategic Monitor Report (2018-2019) and updates its empirical analysis of contemporary trends in IMC.[4] It does so by gauging states’ intention and capacity to engage in such competition, and their actual activity in this realm. This report continues with an analysis of trends within the international order through an assessment of five interstate military competition-related norms and rules.

Trends in interstate military competition

Threats

Intentions

Perceptions of military competition

IMC is increasingly perceived as an important security priority by major military powers. An analysis of the security and defense strategy documents published by the UK, Germany, France, the US, China, and Russia over the last decade shows a shift towards the identification of interstate competition as a concrete security threat. In contrast to their prior focus on terrorism, both the UK and Germany prioritize interstate competition as a vital security challenge, citing respectively the “resurgence of state-based threats”[5] and Europe’s disadvantage in light of increasing international competition due to its traditionally limited defense budgets.[6] France recognizes that “the international balance of power is changing rapidly,”[7] which stirs greater uncertainty and anxiety. The US mentions the hybrid nature of IMC, stressing that “in competition short of armed conflict, revisionist powers and rogue regimes are using corruption, predatory economic practices, propaganda, political subversion, proxies, and the threat or use of military force to change facts on the ground.”[8] The US places even more emphasis upon the “reemergence of long-term strategic competition” and the fact that it must consolidate its military edge vis-à-vis rival powers, most notably China and Russia.[9] Similarly, China’s 2019 defense strategy refers albeit implicitly to the US when noting that the “international security system and order are undermined by growing hegemonism, power politics, unilateralism and constant regional conflicts and wars.”[10] Russia already observed this in 2014, stating that the “world development at the present stage is characterized by increasing global competition.”[11] These examples underscore that states are expecting and preparing for an era of greater interstate competition.

Military threats

The intensification of IMC is not only apparent from state perceptions, but also from the use of threatening rhetoric by various states. This has manifested with particular clarity in recent years. Though US President Donald Trump’s “fire and fury” comment towards the DPRK to his more recent threats to Iran and Turkey in the summer and autumn of 2019 (respectively) have generally received the most screen-time in Western media, military threats have also been prevalent in other parts of the world. The Kashmir region has long represented a flashpoint for the India-Pakistan relationship; India’s Foreign Ministers’ statement that India expects to have “physical jurisdiction” over Pakistan-administered Kashmir one day, issued on September 2019, ties into a wider trend of mutual animosity.[12] Iran’s threat of “all-out war” in the wake of a drone attack on a Saudi oil facility, also in September 2019, further serves to underscore that militarily threatening rhetoric constitutes a phenomenon which can be observed in discourse in competitive dyads around the world.[13]

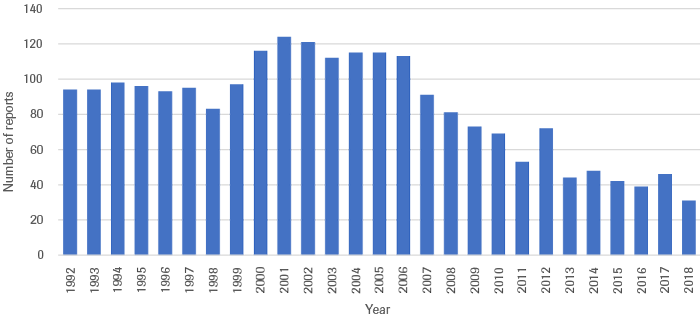

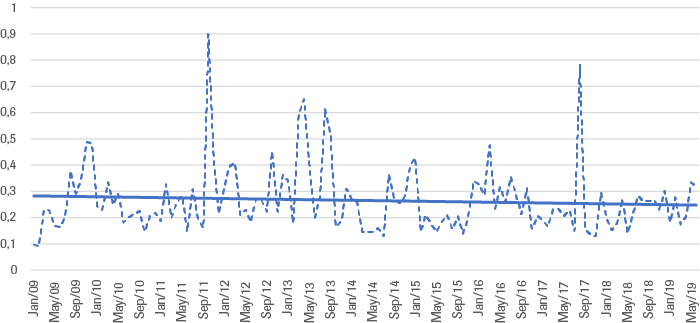

Our analysis of competitive and aggressive language in the form of threats deployed by political and military leaders of permanent members of the UN Security Council using data from the Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS) finds that leaders of great powers have resorted to the use of such rhetoric over the past decade with intermittent peaks; the highest peak was associated with Russia’s annexation of Crimea (See Figure 2). Lower peaks in the period since can be attributed to the US’ placing of sanctions on North Korea,[14] Iran,[15] and Russia,[16] as well as to the rising of tensions in the South China sea, and to the Kremlin’s increased engagement in Middle Eastern power politics.[17]

Source: HCSS calculation using ICEWS data[19]

Taken together, great powers’ increased attention for interstate competition combined with the prevalence of military threats by some powers points towards an increase in IMC. The impact of this increased attention for interstate competition manifests clearly in states’ restructuring of their militaries with an increased focus on preparing for interstate conflict, and significant investments in R&D, as well as in their willingness to wage proxy wars. These themes are explored further in the following sections.

Military capabilities

Military spending

Investments in the modernization of military capabilities are increasing. Recent years have clearly shown this trend in action, with military powers such as China, Russia, and the United States launching ambitious modernization programs, and introducing a domestically developed aircraft carrier,[20] a bevy of high-tech (hypersonic) nuclear-capable missiles,[21] and a new long-range strategic stealth bomber respectively.[22] Not only great powers but also regional powers are revamping their military capabilities, such as for instance Iran which has been making significant progress with its intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) program.[23] In the past decade, investments in these high tech kinetic capabilities are increasingly coupled with considerable investments in military artificial intelligence (AI) applications.[24]

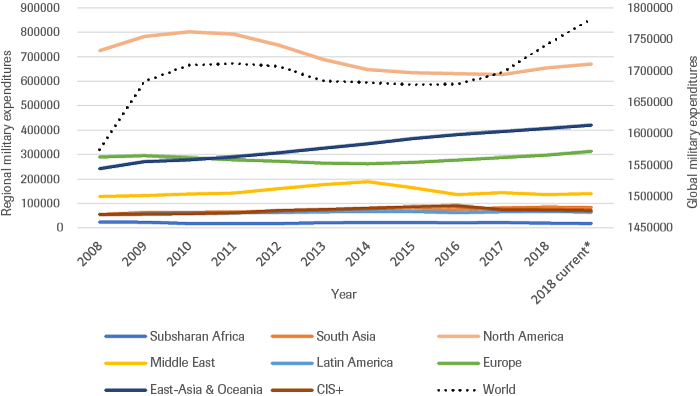

Overall levels of absolute military expenditures are increasing – albeit not significantly – at the international level. Over the ten-year period from 2008 to 2018*, expenditures increased by 13.2%, now amounting to $1,78 trillion in total (See Figure 3).[25] At the same time, in various regions, military expenditures saw a decrease. The only regions with a significant increase over the past decade are East-Asia and Oceania (See Figure 3). Since 2017, Europe and the US have started to slightly increase their expenditures again, but in other regions, for instance Latin America, the downward pattern continues or maintains itself at a low level (relative to the overall military expenses which are still by far the highest in North America). The data on the Middle East, which has been an active conflict hotspot for many years now, are inconclusive because of data unavailability for Syria, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen, all of which are currently embroiled in conflicts and therefore likely to be increasing their expenditures.[26]

* This data presents a preliminary estimate only.

Source: SIPRI[27]

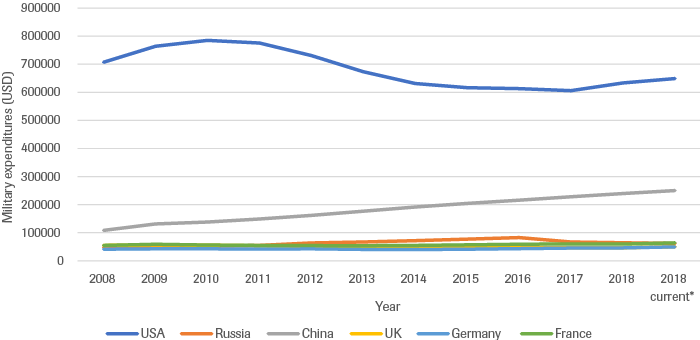

Despite substantial regional variation, military expenditures of key military actors have increased considerably. The most striking example is China, which has doubled its military spending from $120 to $240 billion in the examined period (See Figure 4).[28] Whilst official numbers seem to reveal significant recent decreases in Russia’s military spending since 2017 (lowering by 20% to $66.3 billion), expert reports indicate that much of real military expenditures are concealed in the state’s budget and, when examined closely, could turn out to be as much as 40% higher than before.[29] Western states’ concerns regarding China and Russia also manifest in the data, with increases present in, among others, the US and France.

* This data presents a preliminary estimate only; at the time of publishing, SIPRI has not yet published final figures for the year 2018.

Source: SIPRI[31]

Data on military expenditure is derived from the SIPRI military expenditure database,[32] and measured in constant US dollars (USD).[33]

Defense R&D and procurement

An examination of states’ military procurement and military research and development (R&D) budgets shows that – after stagnating between 2012 and 2014 – these budgets are once again increasing (See Figure 4). States’ pursuit of cutting-edge technologies, as covered in the previous section, plays a central role in the observed increases in military R&D. This is evident in increases in featured states’ R&D budgets, which can be attributed to efforts in military modernization of their armed forces and military capabilities[34] but also in more specific technology-related investments. As an example, US, Russian, and Chinese efforts towards modernization of their nuclear arsenals have manifested in the unveiling of new tactical nuclear weapons,[35] the introduction of nuclear-capable hypersonic missiles, and renewed investments in Theatre Missile Defense (TMD).[36] Modern technologies’ contribution to increases in military R&D are also evident in the uptick in the number of military assets being launched into space, because of states’ increasing dependence on space assets in the waging of (interstate) wars.[37] Outside of the on-the-ground benefits associated with the militarization of space, this on-going development is endemic of a wider trend within IMC:[38] as competition heats up, new domains and frontiers are commanding strategists’ attention.

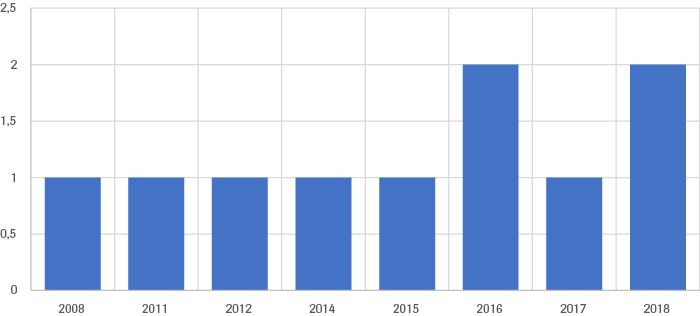

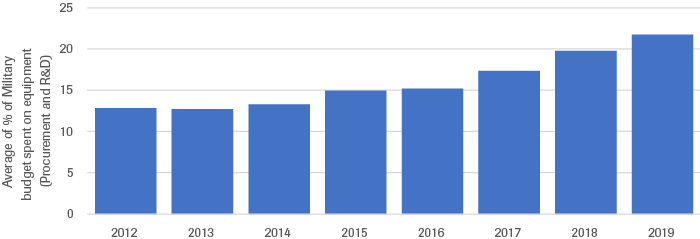

The US is at the forefront of these trends, focusing on the renewal and modernization of its conventional and nuclear capabilities.[39] R&D funding for the development of modern technologies has received the second largest percentage increase in the US military budget request for 2019, which was 11% higher than its 2018 predecessor.[40] Other NATO members are increasingly following suit. Recognition of shortcomings in their military R&D efforts resulted in a 50% increase in allocation.[41] In 2019, NATO members allocated on average 21.7 % of their military budget to equipment procurement and R&D, an increase of 1.9% over the preceding year (see Figure 5). In 2017, the EU also launched the European Defense Fund (EDF) – which will make €13 billion available between 2021 and 2027 – with the goal of supplementing and amplifying national investments in defense R&D.[42] Military ties between EU Member States are further enhanced through a variety of efforts under the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) initiative.[43]

The aforementioned trend is also reflected in China’s and Russia’s R&D expenditures, both of which have implemented a range of programs to modernize their militaries and invest in upgrades of their nuclear capabilities.[44] Russia has committed $700 billion to an armament program which aims to modernize 70% of Russia’s armed forces by 2020,[45] with 59% of Russia’s weapon systems having already been modernized by 2017.[46] Russia has additionally announced its intentions to develop and deploy more autonomous systems, having set itself the goal to make 30% of its military equipment robotic by 2025.[47] Russia’s efforts at military modernization were on full display in October 2019, when the Russian military conducted tests of its forces’ readiness for nuclear conflict as well as of its new UAV-capable artillery systems, communications systems, command-and-control (C2) systems, electronic warfare (EW) assets, large-scale airborne assault forces, and strategic mobility.[48] On the Chinese side, Beijing has also announced intentions to fully modernize its armed forces by 2035,[49] and is focusing on the development of AI applications for military use.[50] In order to do so, China has increased defense spending by 7.5% in 2019, $177,544 billion of which will be allocated to “sustaining, growing, and modernizing” its military.[51] Several cutting-edge systems – including an intercontinental ballistic missile that could allegedly target any region in the US, as well as a range of unmanned systems – were displayed in the 2019 military parade.[52] The breadth of Beijing’s military modernization efforts is further illustrated by recent revelations of Chinese wind tunnel tests of a stealth bomber design,[53] as well as reports of a ‘mothership’ capable of launching vehicles into low-earth orbit.[54]

The size of investments made by the US, China, and Russia underscore the role of AI applications’ role in modern-day IMC. The US has committed to spending $9 billion on AI R&D and is already utilizing a range of autonomous systems (e.g., naval vehicles patrolling the South China Sea and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs)).[55] In September 2018, the Pentagon also committed to spending $2 billion over the next five years through the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to develop new AI technologies.[56] It also set up the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC) to further ensure AI advances for the US military in the future.[57] The JAICs budget will increase significantly from 2021 onward, set to double to over $208 million aimed at facilitating the integration of AI into weapon systems.[58] China and Russia are also increasingly devoting resources to military AI research.[59] Especially China is rapidly advancing in the area.[60] Even though it is not clear how much China spends on military-related AI – largely as a result of the fact that many of Beijing’s investments in dual-use AI-based technologies such as facial recognition may not be reflected in its military budget – several projects speak to its commitment to developing these technologies. Examples include the China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation’s AI-endowed intelligent cruise missile and various autonomous military vehicle development programs.[61] Russia’s forays into AI technologies have so far been predominantly security-focused, being developed for military purposes.[62] The Kremlin’s recently approved 2020-2030 AI strategy departs from this agenda,[63] instead foreseeing accelerated AI development, more scientific research, improved AI-focused education and training systems, as well as enhanced availability of technological resources.[64] The strategy highlights Moscow’s recognition that competing in a military AI race requires the engagement of non-military sectors, and follows the country’s establishment of the National Center for the Development of Technology and Basic Elements of Robotics in 2005.[65] Whilst the budget for Russia’s AI strategy has yet to be confirmed by government officials, leaks indicate that spending is set to double (formerly $490 million).[66] The EU lags behind the US and China in its pursuit of military AI.[67] Nonetheless, initiatives like the European Commission’s Coordinated Plan on Artificial Intelligence,[68] which devotes over EUR 1.67 billion for R&D funding between 2018 and 2020,[69] as well as initiatives of individual member states such as for instance France’s recently launched military AI strategy, which earmarks EUR 100 million to the development of military AI by 2022.[70]

While AI may even turn out to be a ‘first past the post’ technology, its successful deployment in a military context is associated with both negative and positive consequences including reduced operating costs and the preservation of soldiers’ lives by keeping them out of harm’s way.[71] More concerning, however – particularly within the context of IMC – is these technologies’ ability to shorten or even automate the OODA loop, taking the human out of the loop. As early as 2002, the US Air Force (USAF) was testing drone swarms which could determine if, when, and how to engage targets without human intervention.[72] The technologies underlying these early tests have only improved as a result of leapfrogging advances in computing power, the sophistication of sensory arrays, and algorithmic know-how. The resulting systems offer states which succeed in harnessing them a significant strategic advantage: human-operated militaries are unlikely to be able contend with the decision-making speed (and comprehensiveness) of their automated counterparts.[73] This has the potential of disrupting not only the military balance of power, but also of negatively influencing the international order by rendering key aspects of traditional regimes obsolete. It is also likely to increase fog and create more friction, thus increasing the potential for escalation.[74] The pursuit of these technologies increases the risk of ‘hyperwars’ in which the pace of conflict operations is escalated to such a degree that humans can no longer keep up.[75]

Taken together these developments reveal a pattern of military modernization and resource allocation towards new weapon systems, platforms, and R&D of future military technologies, which point towards a rising prevalence of interstate military competition.

Source: NATO[76]

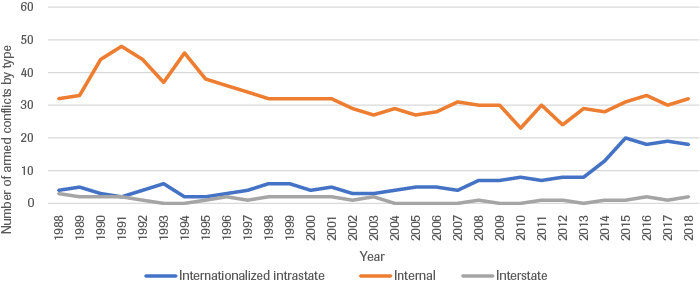

Military activity

Activities relating to IMC show an uptick in the number of internationalized intrastate conflicts, while the number of direct (state-on-state) military conflicts – defined as interstate war – and the number of internal (domestic, civil) conflicts stay relatively constant (with traditional interstate war gravitating close to zero). Several states are taking steps to increase their military footprint internationally, often out of overt geopolitical considerations – particularly on the African continent. These trends speak to an increase in its overall intensity levels. An overview of the number of conflicts, broken down by type (interstate, internal, or internationalized intrastate) is provided in Figure 6 below.

Source: Adapted from UCDP/PRIO[77]

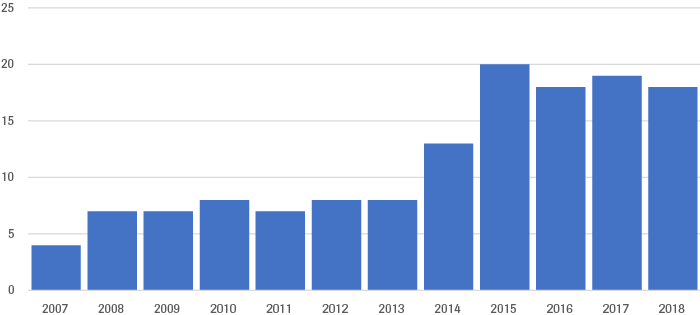

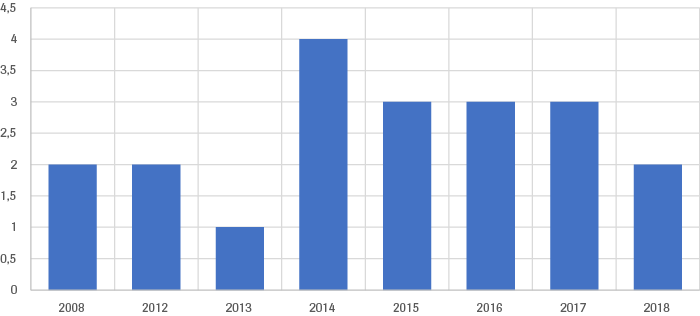

The number of internationalized intrastate conflicts has increased quite substantially: they tripled between 2008 and 2018, increasing from six to eighteen (see Figure 7). Their conflict onset rate increased significantly in 2013 when the number of these conflicts more than doubled from eight to twenty between 2013 and 2014, and regressing slightly (to eighteen) by 2018, thus accounting for 35% of all conflicts in 2018 (as opposed to 18% in 2008).[78] The Middle East emerges as a hotspot when it comes to conflicts of this type, largely as a result of the geopolitical opportunities for foreign meddling brought about by the internal conflicts and power vacuums produced as a byproduct of the Arab Spring.[79]

Internationalized intrastate conflicts, such as the ones currently being fought in Libya, Syria and Yemen, are particular instances of IMC, and are the product of diverging geopolitical interests – some of which are ideologically grounded. Iranian involvement in the violence unfolding in Yemen and Syria can be understood in part through the lens of its religiously motivated disagreements with Riyadh,[81] and represents an extension of the Sunni-Shiite schism that lays at the heart of a number of the region’s contemporary conflicts.[82] Russia’s involvement in the Syrian conflict may be understood at least in part through the Kremlin’s desire to safeguard an autocratic regime as an ally to bolster its position in the region.[83] Also the US’ involvement can be partially understood through the lens of its pro-Israel, anti-Iranian ideological leanings. Simultaneously, these countries’ involvement in Middle Eastern conflicts can be explained through the lens of ‘traditional’ realpolitik-related motivations. Iranian efforts at installing regimes and fostering instability within the region are certainly ideologically motivated but can also be understood as being geared towards maintaining a regional balance of power that is conducive to its regime’s continued existence.[84] Russia may be motivated by its wish to make the world safe for autocracy, but its involvement in the Syrian civil war can also be explained through the lens of the opportunities the conflict offers to test and showcase military tactics and hardware,[85] its patron–client relationship with the Assad regime,[86] and the strategic advantages associated with the expansion of its naval facility in Tartus.[87] US President Donald Trump’s telling but mistaken claim that the “oil is secured”[88] captures that US’ involvement in the region is certainly also motivated by the region’s richness in resources.[89]

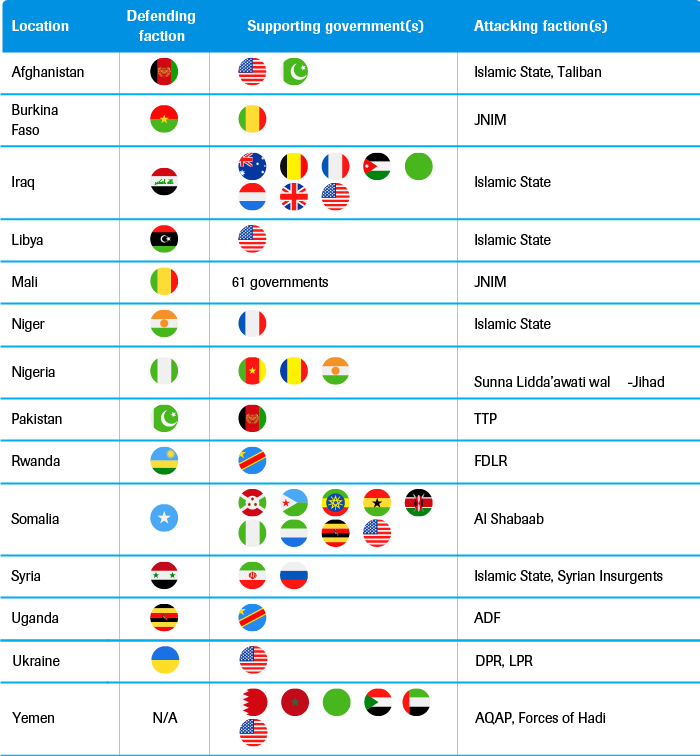

Table 1 provides an overview of all internationalized intrastate conflicts ongoing in 2018. This table does not offer a comprehensive overview of state involvement in the included conflicts as a result of its coding methodology.[92] This results in several key actors, the US included, being omitted from the country lists in some cases because they are not necessarily aligned with government forces. Nonetheless, it offers helpful insights into the nature of modern-day IMC. Internationalized intrastate conflicts in which one or more great or middle powers are involved all offer resource and/or ideologically-based incentives. This is the case in many of the Middle Eastern conflicts, as well as in several of the ongoing African conflicts (Niger, Somalia). Competition, both military and otherwise, over the African continent has heated up in recent years, with China and Russia having most recently attracted media attention with their efforts.[93] The US also engages in this competition, for example through the creation of a new drone base in Niger for $110 million, opening lines of communication to large swathes of North and West Africa.[94] Great power competition over the continent is also increasingly supplemented by assertive actions on the part of middle powers. This manifests in (among others) the United Arab Emirates’ and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s efforts in setting up a peace deal between Ethiopia and Eritrea while securing the rights to military bases, ports, and trading outposts in those countries in the process.[95] These developments do not neatly fall into the ‘activity’ category of IMC, in that they represent non-kinetic forms of engagement, but are nonetheless indicative of increasing awareness of the continent’s strategic importance, both militarily and otherwise.

The observed increase in the volume of internationalized intrastate conflicts is indicative of an uptick in the prevalence of IMC, particularly when viewed through the lens of these conflicts’ increased occurrence rate in geo-strategically important regions. Because these conflicts carry with them a significant risk of escalation,[96] and due to their destabilizing nature and close proximity to European borders, an uptick in their occurrence rate can also be associated with an increase in the threat level associated with IMC from the Netherlands’ perspective.

International order

Various elements of the previously explored aspects of IMC are regulated by – and codified in – international law. As an example, the making of military threats is outlawed in Article 2 (4) of the UN Charter, which prohibits states from using the “threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state,”[97] thus offering a mechanism for enforcing both instances of military threats (intentions) and instances of violation of state sovereignty (activity). Several international treaties, including the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) of 1970 and the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) of 2014, aim to mitigate the destabilizing effect of arms races through the introduction of standards and verification mechanisms.[98] Such treaties are supplemented by other international initiatives to constrain IMC such as the Open Skies Treaty (1992),[99] the Vienna Document (1990),[100] and the Wassenaar Arrangement (1995)[101] – which contain confidence-building measures, and thus touch on the dynamics which have been previously touched on under this report’s capabilities section.

This section explores trends within the aforementioned legal regimes on the basis of a systematic analysis of relevant developments of the past ten years, with the goal of assessing the health of the international legal framework governing IMC. The analysis establishes that the legal framework governing IMC at the international level faces significant erosion, with negative trends manifesting in both the degree to which states break the rules upon which it rests, as well as in the infallibility of the norms that underpin those rules. One factor driving this erosion presents in the form of new technologies, which are as of yet not convincingly governed by international law but which – as previously outlined – are increasingly emerging as a relevant domain within modern-day IMC. The field of military AI has gained noteworthy international traction as of late, as countries’ concerns over the destabilizing nature of military AI applications’ deployment continue to grow.[102] Regulation in this field is predominantly promoted by Western countries, but several hurdles remain, most notably the international community’s inability to agree on the definition of lethal autonomous weapon systems and the notion of meaningful human control.[103]

The growing role of space, due to its strategic and commercial importance and its accessibility to public and private entities, is yet another area of contention. This is due to the fact that the 1967 Outer Space Treaty predates the rapid evolution of current developments. For instance, the increasingly witnessed militarization of space is not explicitly prohibited by the Outer Space Treaty, but the increasing commercialization of space in combination with its nascent weaponization, is now driving calls for more regulation of space,[104] as well as revision of the Treaty.[105] States will need to consider their standing in the space domain, as (legislative) initiatives by trendsetters will require other states to respond.

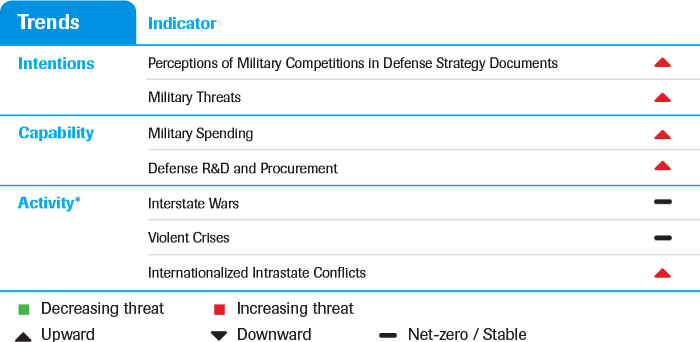

A high-level appraisal of the trends observed within the international regulatory framework governing IMC can be found in Figure 8 below.

The following sections provide an in-depth overview of trends over the course of the past decade which have manifested within the international legal framework governing IMC. The analysis reveals an international order under pressure, with several rules having experienced increasing degrees of non-compliance. The salience of several norms (“states ought not to use or develop nuclear weapons” and “states ought not to engage in threatening behavior”) has also been reduced.

States ought not to use or develop nuclear weapons

The past decade has seen an erosion of both nuclear arms control regimes and the norm that underpins them. The regulatory framework pertaining to this norm can generally be understood as splitting between measures relating to nuclear nonproliferation and controls on the development and deployment of delivery vehicles (arms control). Within the context of this research, the framework geared towards enforcing nuclear nonproliferation is measured through an analysis of developments within the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), while the framework geared towards arms control is measured through an analysis of developments pertaining to the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) and the New START. At the macro level, these treaties all exhibit a consistent downwards trend in compliance, with the result being an erosion of both the regulatory framework (the rules) and the normative framework (norms) that underpins it. These can be partially attributed to the outdated nature of several of the key bilateral treaties within this domain, but also to the fact that IMC is driving the development of new nuclear weapons and delivery vehicles as a means to defend national security.

Nuclear nonproliferation framework

Starting with the multilateral framework governing nuclear non-proliferation, this consists mainly of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which exhibits a ‘neutral’ trend of compliance over the past ten years. In the case of the NPT, this neutral trend can be attributed to the fact that its main objective is to reduce the number of nuclear weapons states (NWS). Because no new states have procured nuclear weapons in the past decade, the treaty remains functional on the surface.[106] This notwithstanding, several developments can be viewed as putting it under strain. These include Iran’s continuing forays into the development into nuclear-capable ballistic missiles, the dissolution of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and Tehran’s subsequent restarting of its gas centrifuges,[107] Donald Trump’s antagonistic foreign policy towards multilateralism and musings regarding the potential upsides of other states obtaining nuclear weapons,[108] and the DPRK’s continued development and testing of nuclear-capable delivery vehicles.[109] In addition, the lack of uniform compliance with the framework – not all signatories have ratified the Comprehensive Safeguards Agreements, which are key to the enforcement of the NPT – is a cause for concern.[110] This negative caveat is corroborated by the Stanford Center for International Security and Cooperation, which identifies an unprecedented level of degradation over the past ten years.[111]

Arms control agreements

Agreements between the world’s biggest nuclear powers, the US and Russia, are (or were) of paramount importance to nuclear arms control. Outside of these agreements, no binding treaty – save the Missile Technology Control Regime (omitted here because it covers conventional weapons systems) – is of direct relevance to the control of nuclear-capable delivery vehicles. The high degree of uncertainty vis-à-vis the longevity of the agreements governing these states’ nuclear relations, which is made visible by increasing hostility in their relations, registers negative trends overall, with the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) being proclaimed “dead” as of February 2019.[112] Russia was initially accused of violating the INF through the testing of a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) designated SSC-8 in 2014, which is prohibited under the INF.[113] Russia has in return accused the US of infringing on the treaty by repurposing its missile defense launchers to work with prohibited missiles, and has lamented the US’ withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) treaty.[114] The INF was widely regarded as a meaningful milestone in efforts to curb the nuclear arms race between Russia (then the USSR) and the US.[115] The treaty’s “death” is regarded as signaling a significant erosion of the international nuclear arms control framework, not only because it affects the world’s two foremost nuclear powers, but because it opens the door to a new arms race, thus undermining the norm that states ought not to use or develop nuclear weapons in the process.

Moving on to the 1991 START I treaty, the control of nuclear arsenals and periodic verification between the two major nuclear powers has remained constant. This trend continued with the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which was signed by presidents Obama and Medvedev in 2010 and which is up for renewal in February 2021. The New START attempts to limit the nuclear stockpiles of both powers while producing a framework for trust and communication.[116] Compliance with the New START has been assessed as satisfactory, with both parties having kept their stockpiles below the agreed-upon threshold as of 2019.[117] This notwithstanding, the New START’s positive impact is likely to subside in the near future as a result of (among others) the Trump administration’s insistence that the treaty be expanded to include China,[118] which calls the certainty of its extension past February 2021 into question.

Assessment of the state of the international nuclear arms control regime

Several trends point towards an erosion of the rules underpinning the norm that states ought not to use or develop nuclear weapons. While the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) has not technically been infringed on, the activities undertaken by Iran, and the DPRK’s continued development of nuclear weapons and nuclear delivery vehicles, despite the fact that the country is not a signatory of the NPT, have a similar (negative) effect, and means that – though compliance with the rule is neutral ‘on paper’ – it, realistically speaking, faces erosion. Of equal concern are the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) and the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START). The INF’s dissolution has contributed to the creation of an apparent domino effect, which threatens the New START extension, and its abandonment by the US and Russia – the world’s foremost nuclear powers – constitutes a strong indicator of the erosion facing the rules-based order enforcing nuclear arms control.

Simultaneously, the norm that states ought not to use or develop nuclear weapons is also viewed as facing active erosion. Multilateral agreements are thin and limited, and in many cases do not cover – or place verifiable compliance mechanisms on either nuclear weapons of non-signatories or their means of delivery. This erodes the norm because it means that, outside of Iran (which is now also no longer limited by the JCPOA), middle powers as well as China are as of yet effectively omitted from comprehensive agreements such as the INF and New START. The DPRK, India, Israel, and Pakistan (all of which are nuclear powers) are not signatories of the NPT, and thus enjoy (on paper) a relative degree of autonomy when it comes to their nuclear modernization efforts. Treaties such as the New START were originally designed for a bipolar world, but today, China is developing and strengthening its nuclear arsenal, at the same time as states such as Pakistan and India are updating their nuclear weapons capabilities as key components of their strategic defensive postures.[119]

The norm that states ought not to develop nuclear weapons is also eroded by the development of new technologies, including air-launched and boosted-glide weapons, 2nd-generation Multiple Independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) capable missiles, nuclear-powered ICBMs, and low-yield and variable yields nuclear weapons. The development of these technologies is not explicitly prohibited under existing agreements,[120] but oftentimes results in the introduction of dynamics which undermine the spirit of existing security structures. As an example, the nuclear-capable hypersonic weapons such as the US’ X51-A, the Russian Avangard, and the Chinese DF-ZF undermine the effectiveness of the early-warning and command-and-control systems which came into being as a response to the advent of the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) in the 1950s.[121] Hypersonic weapons’ ability to travel at speeds surpassing Mach 5 makes them much more difficult to track and shoot down using conventional air defense systems.[122] Because these weapons’ travel speed reduces the time between launch and impact to as little as ten minutes, they also significantly undermine defending states’ second strike capabilities, thus undermining a key tenant of the existing nuclear power balance.[123] A similar dilemma presents in AI-enabled missiles’ ability to avoid conventional air defenses.[124] This highlights the need for more comprehensive regulations on not just the quantity of nuclear stockpiles, but on the delivery vehicles which accompany them. All of this yields a negative appraisal of the overarching norm that states ought not to use or develop nuclear weapons. This assessment is circumstantially corroborated by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ Doomsday Clock, which has observed a negative trend since 2010, warning that “it’s still 2 minutes to midnight”.[125]

States ought to adhere to conventional arms control regimes

Much like the regime regulating nuclear non-proliferation (see previous subsection), the regime regulating the nonproliferation of conventional arms faces erosion. Rules included in this analysis are Article 36 (Protocol 1, Geneva Convention), the Open Skies Treats (OST), the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE), the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), and the Vienna Document. An analysis of developments affecting the Wassenaar Arrangement, the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), The Hague Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation (HCoC), the UN Register on Conventional Arms (UNROCA), and the Guiding Principles formulated by the 2018 Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on Legal Autonomous Weapons (LAWS) is also included. Trends within these treaties show a consistent downwards trend in compliance, with the result being an erosion of the regulatory framework (the rules). The trend remains neutral on the normative side, however – largely as a result of states’ continued willingness to opt into international treaties pertaining to the subject (despite their reluctance to observe the compliance verification mechanisms).

Rules pertaining to new technologies and the restriction of inhumane weapons

Overall, the development of the rules governing ‘new weapons’ is tentatively positive, with increases in rule adherence, as well as the reaffirmation of Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems’ (LAWS) inclusion in Article 36 adding up to a positive trend in the perceived relevance of the associated norm.[126] Article 36 of Protocol I to the Geneva Convention, which imposes on states the obligation to scrutinize the development of new weaponry against applicable international law, marked an increase in adherence, with seven additional states ratifying the treaty in the past ten years.[127]

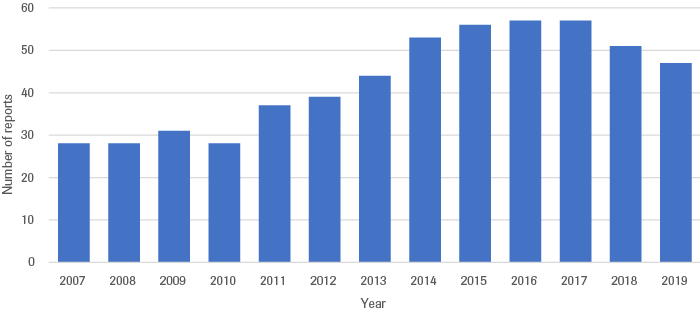

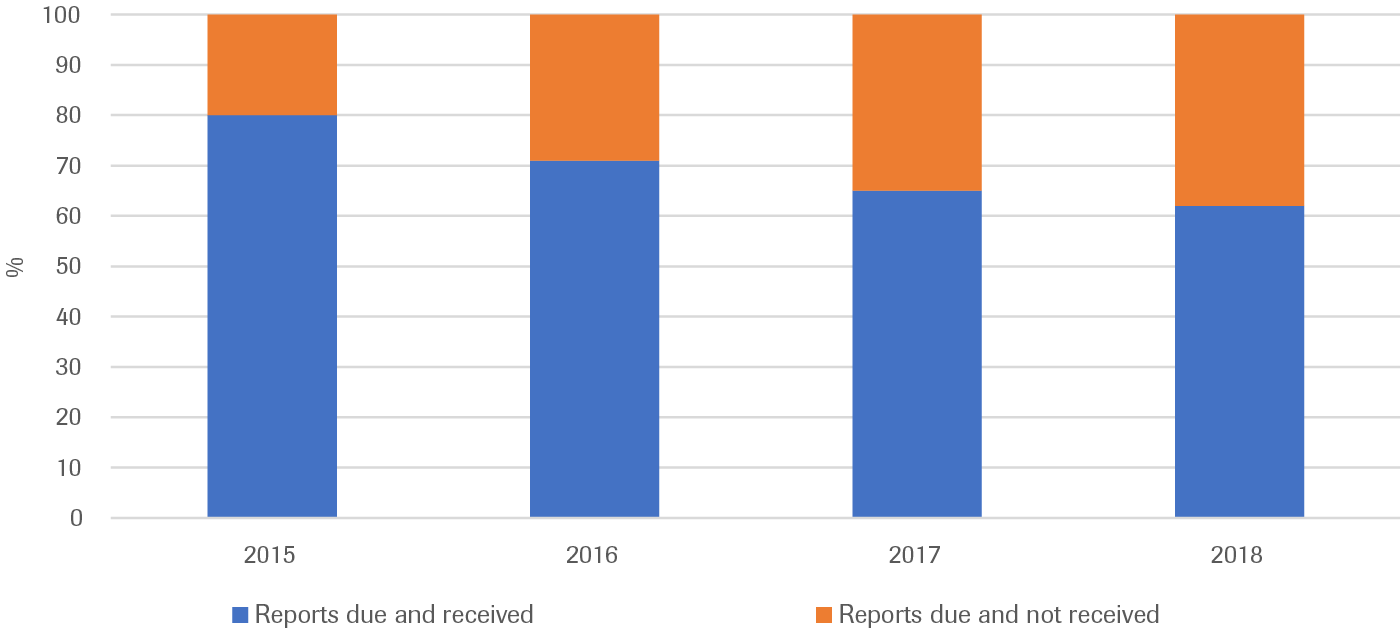

During the same period, the debate related to this article pertained overwhelmingly to the issue of LAWS. While in 2011 the compliance with the mandatory review with regards to LAWS was a source of beginning concern,[128] in 2016 the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) reported “unprecedented levels of attention” for this obligation.[129] The Treaty on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW),[130] which also saw a spike in adherence (seventeen states joined from 2008, adding up to 125 parties overall),[131] underwent a major development between 2014 and 2018, and established a group of experts on LAWS.[132] General compliance with the reporting obligation improved from 2009, with a mild slowdown in the past two years (see Annex I). In 2019, however, the UN Secretary-General noted that progress of the Group of Governmental Experts on Legal Autonomous Weapons (GGE) in particular was insufficient,[133] and a comprehensive regime for curbing these weapon systems’ development and deployment has yet to be formulated.[134]

Arms transfers

The framework on international arms transfers, from missile and dual-use technology control to the tools aiming to map all arms transfers, has shown a negative development over the course of the past ten years, though some positive developments warrant attention (outlined below). The Wassenaar Arrangement has run relatively smoothly since 2009,[135] with Mexico joining in 2012,[136] and has extended its focus area to include issues of energy density in 2016 and cyber technology in 2018.[137] The Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) was not contested over the reporting period, [138] and may – on the initiative of the Trump Administration – even be expanded to cover drones and other ‘slow moving’ weapons’ delivery systems in the future.[139] India joined in 2016 and the regime provided the gateway to Indo-Russian cooperation on innovation of Indian Brahmos missiles.[140] Similarly, The Hague Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation (HCoC) expanded its membership to include six additional states (including India in 2016) to the current 140.[141]

Positive developments within the aforementioned treaties are somewhat diminished by their lack of meaningful – or any – compliance mechanisms. As an example, HCoC does not impose any compliance mechanisms, meaning that commitment cannot be verified and that the observed positive trend in adherence speaks little to states’ factual compliance. While these treaties’ expansion contributes to this study’s neutral appraisal of the norm because it indicates that states are willing to signal their support for its underlying principles, the gesture may ring hollow because it need not result in meaningful changes in behavior. This statement is particularly true when viewed within the context of developments pertaining to the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) and the UN Register on Conventional Arms (UNROCA) – both of which do incorporate meaningful control mechanisms. While the ATT saw a significant rise in adherence since its entry into force in 2014,[142] compliance with the national reporting obligation has plummeted in recent years (see Annex I) and its accuracy and transparency was found to be extremely low.[143] Moreover, the US announced its intention to withdraw from the ATT in 2019, thus significantly reducing its international salience.[144] Compliance with reporting in the UNROCA has also exhibited a steady decline, reaching yet another all-time low in 2018 (see Annex I).[145] Reductions in the compliance rates of the aforementioned treaties contribute to the negative trend appraisal featured in Figure 8, and outweigh – from a rules-based perspective – the relevance of increases in state adherence to non-binding treaties.

Conventional arm force reduction, trust building and stockpiling verification arrangements

Three documents became the mainstay of provisions regulating conventional arms control in post-Cold War Europe, counting roughly the member states of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), namely: the Vienna Document (VD), the Open Skies Treaty (OST), and the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE). These documents were intended to reduce the size of armed forces while allowing for mutual verification measures, thus enhancing trust and preempting the emergence of new tensions.

As opposed to what can be observed in the framework governing new technologies and, to some extent, arms trade, the observable trend pertaining to these three treaties is decidedly negative. One treaty (the CFE) is defunct, one regularly breached and in deadlock (VD), and the OST is on the verge of collapse. Despite some undeniable level of agreement over the rationale of at least the VD and the OST, significant setbacks are encountered on all remaining levels of analysis.[146] While compliance with the VD remained robust prior to 2008,[147] it has faced erosion as a result of new strains in the US–Russia relationship.[148] Though some exchange still occurs under its umbrella and it can be credited with facilitating some inspections,[149] its loopholes are generally perceived as rendering it ineffective, with Russia meanwhile opposing any reform.[150] The OST enjoyed reasonable compliance until 2015, with one hundred flights executed yearly.[151] Since then, Russia and the US have engaged in the implementation of tit-for-tat restrictions. This process intensified in 2017 and 2018, with the effect being that the treaty’s continuation after 2019 is uncertain.[152] The CFE has been de facto irrelevant for the past ten years,[153] as a result of Russia suspending its implementation in 2007 and terminating its participation in the dispute resolution mechanism in 2015.[154] It should also be noted that these treaties were not designed to cope with the nature of emerging technologies, which may further limit their relevance and applicability, while any reform is, at the moment, not very likely to be executed soon.

The final, and perhaps the most significant, setback of these documents is the restricted character of membership. Many middle and great powers simply do not adhere to them, and comparable global verification and conventional arms reduction arrangements are non-existent, while these remnants of the post-Cold War order show no signs of motivation to expand – rather the opposite. Their evident collapse, however, has a global effect beyond the decreased arms control within the OSCE cohort at least in that any efforts to emulate such trust-building arrangements elsewhere will be discouraged, which dangerously erodes this aspect of the norm regulating conventional arms.

Assessment of the state of the international conventional arms control regime

The rules underpinning the norm that states ought to adhere to and comply with conventional arms regimes has, despite a select few positive developments, eroded over the course of the previous decade. Though the past ten years have seen a rise in formal adherence, i.e., signatures and ratifications of rules governing this behavior, as well as – in some areas – the expansion of select treaties and regimes, two negative developments serve to contribute to the norm’s erosion. First and foremost, the heavy, recent strain deriving from bumps in the US–Russia relationship has served to undermine the integrity of trend-setting agreements such as the Open Skies Treaty (OST) and the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE). Second, virtually all treaties containing compliance measures,[155] as opposed to mere formal adherence provisions, have exhibited significant deterioration, as evidenced for instance by the ATT: although an increasing number of states pledges to adhere to the underlying rationale of the treaty, the number of submissions of the mandatory reports has plunged.

This notwithstanding, the adherence to the norm related to conventional arms regimes is not viewed as declining for two reasons. First and foremost, the individual regimes and documents explored within this analysis show meaningful efforts at incorporating new technologies. Even despite the fact that the world’s great powers are often accused of stalling and manipulating negotiations,[156] several positive developments – including the ratification of the new Joint Declaration for the Export and Subsequent Use of Armed or Strike Enabled Unmanned Aerial Vehicles of 2016, the mere fact that discussions regarding the legality of Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems (LAWS) are ongoing, and the Missile Technology Control Regime’s (MTCR) possible future inclusion of slow-flying UAVs – offer some reason for optimism. Second, the vocal condemnation of deteriorations relating to the trust-building and verifications mechanisms speaks to the presence of an international community which continues to value the basic principle of the norm that a control of the development, transfer, and use of conventional arms is desirable.[157] Increases in adherence to the Wassenaar Arrangement, and the The Hague Code of Conduct against Ballistic Missile Proliferation (HCoC) also contribute to the norm’s neutral appraisal, as they indicate that – although the rules are being complied with less consistency – states still place value in the notion that trade in conventional arms ought to be regulated at the international level.

States ought not to engage in threatening behavior

This analysis establishes that the rules underpinning the notion that states ought not to engage in threatening behavior have faced no significant decrease in compliance over the course of the past ten years, but nonetheless argues that the norm itself has been eroded. The assessment of a stable rule is based on the fact that, while states frequently violate Article 2(4) by threatening one-another,[158] the volume and intensity of this threatening behavior have not increased significantly at the global/system level over the course of the past decade. The norm is conceptualized as facing erosion though largely because the advent of hybrid tactics has allowed states to actively pursue objectives which run contrary to it without infringing on it in the formal sense.

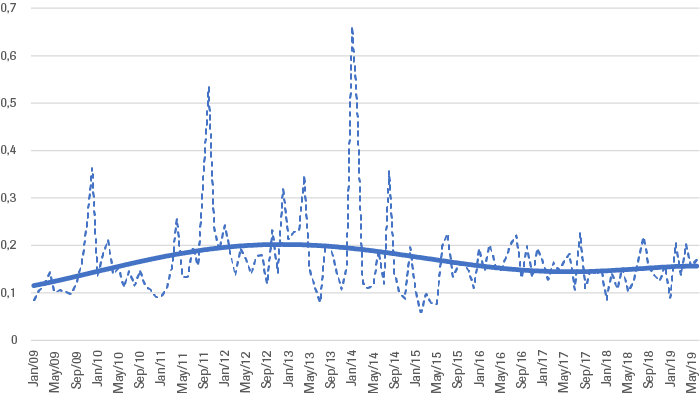

The norm that states ought not to engage in threatening behavior is codified in international law by means of Article 2(4), which states that “all members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.” The norm (states ought not to engage in threatening behavior) cited in this section is intended operationalize trends relating to states’ compliance with the international legal (and normative) framework governing their intentions rather than their actions. Consequently, though Article 2(4) also covers instances of the use of force, events pertaining to actual instances of state-state violence are handled in the next section, which deals with infringements of state sovereignty. In the absence of a comprehensive database outlining the volume of Article 2(4) violations – a result of (among others) ongoing discussions vis-à-vis the article’s interpretation – the analysis offered here relies on expert judgment, supplemented by ICEWS-derived data of threats in interstate relations presented in Figure 9.

Though the quantitative analysis offered in Figure 9 does not indicate that the rate of non-compliance has increased significantly over time, several recent events warrant concern – as they are potentially indicative of a significant future (further) erosion of both the norm and its associated rules. The tit-for-tat exchange of threats between the US and the DPRK during the first year of the Trump administration represents a violation of the Article’s prohibition of threats of the use of force.[159] Other topical examples include Donald Trump’s letter to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in which he threatened to “destroy the Turkish economy” in October 2019,[160] Vladimir Putin’s nuclear saber rattling,[161] back-and-forth coercive messages between Washington and Tehran,[162] as well as the recurring military threats between Riyadh and Tehran in the aftermath of the bombing of Saudi Arabia’s oil fields.[163]

Source: HCSS calculation using ICEWS data[164]

The lack of significant change within the rule notwithstanding, the norm associated with Article 2(4) is facing erosion because a number of important military powers are deploying military threats in a number of dangerous situations in recent years, thereby effectively changing the standard of common discourse. This is further aggravated by the increased prevalence of hybrid tactics. The prevalence of hybrid tactics’ negatively impacts the norm, because gray zone operations fall below the legal threshold of war.[165] Hybrid tactics such as cyber measures or informational operations exploit the lack of definition of “use of force” in Article 2(4), which is often associated with a particular “threshold of violence,” in order to “fly beneath the radar.”[166] The proliferation and normalization of hybrid tactics in state toolkits negatively impacts the norm because these measures constitute a conscious effort to achieve objectives which are incompatible with the sentiments enshrined in Article 2(4). State engagement in such efforts cam thus generally viewed as being indicative of a lack of subscription to the sentiments underlying the norm itself, as they constitute adherence by ‘technicality’ rather than by moral principle. Hybrid warfare and gray zone operations are a key aspect of modern power politics, and political influence, and can be used to propagate a range of threatening behaviors, both military and non-military.[167] Hence, the increasing presence of hybrid measures of coercion throughout the last ten years presents a negative trend in compliance with the norm here discussed.[168]

States ought to respect territorial sovereignty and inviolability

The following section assesses the extent to which the norm and rules pertaining to the respect of territorial sovereignty were observed in the past decade. Given the complexity of the matter and its primarily legal nature, several methods are used in order to substantiate the conclusion that while the rules face increasing erosion, the norm is stable. Firstly, the number of state-on-state conflicts is assessed in order to evaluate the extent to which this type of conflict occurs. Simultaneously, the lawfulness of recent state-on-state contentions is assessed based on the legal opinions of relevant institutions. The second section will complement these observations through the collation of a list of the actions and justifications employed by states whose activities may be seen as infringing on the actions-related intent of Article 2(4).

Occurrence of state-on-state violence and the records of IGOs on their lawfulness

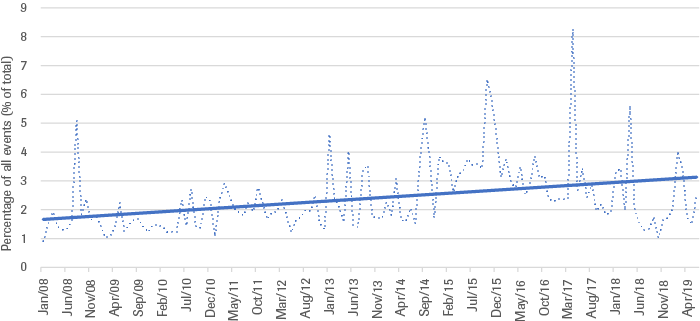

In stating that “all members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations,” Article 2(4) of the UN Charter covers both intentions (addressed in the previous section) and actions. The analysis in this section relies partially on an appraisal of ICEWS-derived instances of actions-based infringements of Article 2(4), as covered by instances in which one state has employed conventional force (aerial weapons, blockades, CBRN weapons, etc.) against another. The previously outlined finding that the number of internationalized intrastate conflicts quintupled between 2007 and 2018 (see Figure 7, Annex II), combined with the uptick in state actors’ use of conventional force in Figure 10, corroborates the notion that the rule pertaining to the actions-based portion of Article 2(4) has faced significant erosion.

Source: HCSS calculation using ICEWS data[169]

Both debates regarding the legality of developments such as the interventions in Libya, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen and the situation in the South China Sea indicate an erosion of the rules-based order, and the uptick in state-based violence, seen in Figure 7, Figure 10, and Annex II, appear to indicate an erosion of norms and rules pertaining to the inviolability of state sovereignty. This finding is not mirrored in trends pertaining to international institutions’ judgments, largely because these institutions face internal (political) deadlocks.[170] An analysis of the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) and United Nation Security Council’s (UNSC) declarations shows no uptick in the occurrence rate of judgements and condemnations of unlawful state-on-state violence.[171] Despite acknowledging certain “threats to peace,” the UNSC has not once noted an outright breach of Article 39 – and, by extension, Article 2(4) – with respect to territorial integrity.[172] Although discussions pertaining to what some perceived as an excessive and inadequate understanding of Article 51 on self-defense occurred within the UNSC over the reporting period,[173] they did not result in any radical change of the reading of the rule.[174] The ICJ, for its part, was predominantly solicited to resolve disputes related to border delineation, often regarding maritime access,[175] with no significant decisions being taken relating to state sovereignty.

States’ actions and justification

Shortcomings in the salience of data derived from an analysis of rulings made by the UNSC and ICJ mean that – while the erosion of the rules-based system is evident in the observed uptick in conflict occurrence (see Figure 7, Figure 10, Annex II) – further analysis is necessary to establish trends pertaining to the norm. An examination of states’ justification of noteworthy instances of interventionism indicates the norm’s continued relevance, to the extent that states continue to feel the need to justify their behavior, often going so far as to cite legal precedent or to secure invitations from host government. This is visible in among others Turkey’s calling on the right to self-defense under the UN Charter as justification for its intervention in Syria (2019);[176] the US-led coalition’s reference to the resolution 2249 and its inclusion of an authorization to eradicate terrorism in Syria (2015);[177] Saudi Arabia’s going to great lengths to demonstrate the legality of its intervention in Yemen by invitation in what amounts in their view to an international attack (Iran’s support of rebels, 2015);[178] and Russia’s invocation of the right of self-determination and humanitarian intervention both in Ukraine (2014) and Georgia (2008),[179] recalling the precedent set by NATO’s intervention in Kosovo. Similarly, Article 51 on the right to self-defense was invoked over the reporting period by a great number of entities appearing in Annex II, including Azerbaijan,[180] Cambodia, Thailand,[181] Sudan, South Sudan,[182] Ukraine,[183] India, and Pakistan.[184] Conversely, no express contestation on the non-validity of the rules and the overarching norm can be observed among states.

Insofar as states do not cease to employ argumentation that finds robust ground in the existing legal framework, a conclusion can be drawn that the norm persists. However, the questionable solidity and instrumental use of the arguments leads to a negative appraisal of the observance of the rules.

Assessment on state of states’ respect for territorial sovereignty

Albeit often depicted as deteriorating, this research finds that the norm of territorial sovereignty as a guiding principle of international relations remains functional. This is because state actors show signs of continuing to consider the norm of territorial sovereignty to be legitimate, as exhibited in not only the lack of significant increase of state-on-state conflicts, but also in their justification for the possible circumvention of individual rules. Stability within the norm comes even as the rules underpinning it face erosion, as evidenced by the previously outlined increase in the onset rate of state-based violence (see Figure 7, Figure 10, Annex II).

Conclusion

This paper has examined trends relevant to interstate military competition by assessing states’ intentions, capabilities, and activities relating to the phenomenon. Overall, it can be noted that IMC is intensifying.

States perceive the security environment as increasingly hostile and competitive whilst some conflict dyads frequently feature the use of military threats. State involvement in intrastate conflicts has increased, and states increasingly make use of hybrid tactics. Military expenditures have increased only marginally at the global level, but leading states have certainly, in some cases steeply, increased their expenditures while also stepping up their investments in the modernization of their armed forces. Not only existing capabilities are being renewed but considerable innovation funds are channeled towards emerging technologies such as AI and new frontiers such as space. The recorded uptick in the number of internationalized intrastate conflicts further speaks to increased competition between states. The competitive nature of these conflicts raises the risk of escalation, meaning that an uptick in their intensity and occurrence rate translates into an increased risk that also the Netherlands’ armed forces will find themselves embroiled in a future military confrontation.

The observed uptick in interstate military competition has ramifications for the international framework which governs it. Both the norms and the rules pertaining to the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons and the control of associated delivery vehicles face erosion. Existing agreements’ omission of several nuclear powers combined with the volatility of the security environment is resulting in the non-extension of existing agreements. The view is slightly rosier within the conventional arms control regime, where a reduction in compliance of verifiable rules included in this analysis speaks to the erosion of the rule, but where an uptick in adherence (among other things) results in a neutral appraisal of the underlying norm. An analysis of Article 2(4) – and states’ adherence thereto – results in a neutral appraisal of the rule (the volume of noncompliance has not increased significantly over the course of the past decade), while the advent of hybrid tactics and states’ engagement therewith leads to a negative appraisal of the norm. Finally, the norm of state sovereignty remains neutral as a result of states’ continued adherence, while a reduction in compliance to the laws which enforce it results in a negative appraisal on the rules side. Competition and technology-related dynamics have played a particularly pronounced role in fostering the aforementioned negative trends. It is therefore imperative to adapt and further develop the international arms control architecture to curtail IMC’s growing intensity level.

Annex

Annex I: States ought to adhere to conventional arms control regimes

Annex II: States ought to respect territorial sovereignty and inviolability

| 2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cambodia (Kampuchea), Thailand |

X |

||||||||||

| Djibouti, Eritrea |

X |

||||||||||

| Eritrea, Ethiopia |

X |

||||||||||

| India, Pakistan |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||

| Iran, Israel |

X |

||||||||||

| South Sudan, Sudan |

X |

Source: UCDP[189]

Source: Adapted from UCDP/PRIO[190]

| 2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azerbaijan |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||

| DR Congo |

X |

X |

|||||||||

| Georgia |

X |

||||||||||

| Ukraine |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||

| Yemen |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Source: Adapted from UCDP/PRIO[191]