Executive Summary

This Strategic Monitor 2019-2020, Between Order and Chaos? The Writing on the Wall, examines the structural long-term trends and current events that shape the global security environment and that influence Dutch national interests and values. This year’s report looks in more detail at the emergence of a new world order, or rather, orders. The report describes and analyzes the most important developments in the international regimes that form the international order. In seven chapters the trends and developments in international relations and the Dutch security environment are studied and interpreted, taking stock of the world today and tomorrow.

This Strategic Monitor examines the trends and developments with regard to the six most urgent security threats from Worldwide for a safe Netherlands: Integrated Foreign and Security Strategy 2018-2022: military threats, cyber threats, unwanted foreign interference and undermining, threats to vital economic processes, the threat of chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) weapons, and terrorist attacks. Most indicators for these six themes point to an increased threat for the coming five years. The trends and developments in the international order reveal a predominantly negative picture with regard to four themes: military competition, hybrid conflict, economic security, and CBRN weapons. For all four of these themes, the degree of cooperation in the international order is shifting towards a greater struggle over the norms and rules of the existing regimes. Trends and developments related to new rules development in cyberspace and rules compliance in counterterrorism are, however, decidedly more positive in nature. Here we see the development of new standards in cyberspace and increasing cooperation in the international efforts to combat terrorism.

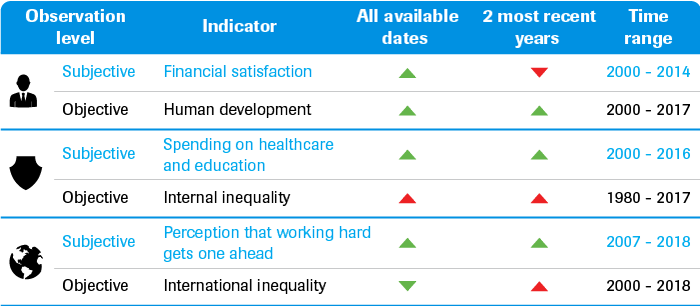

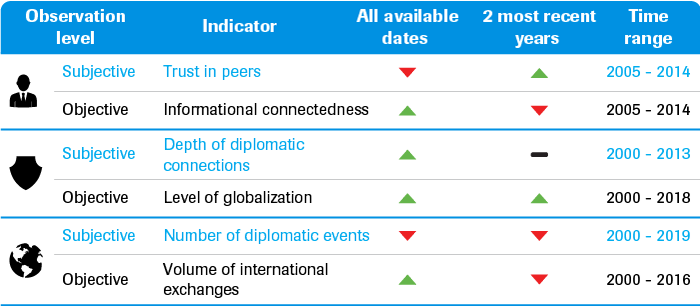

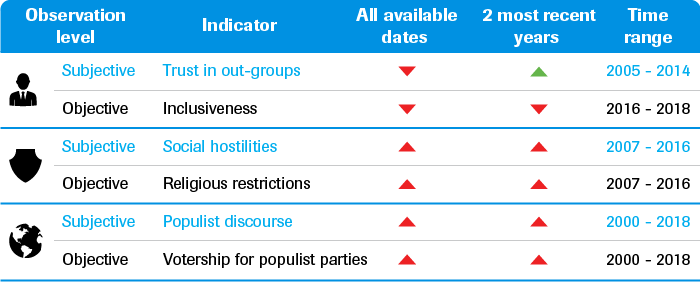

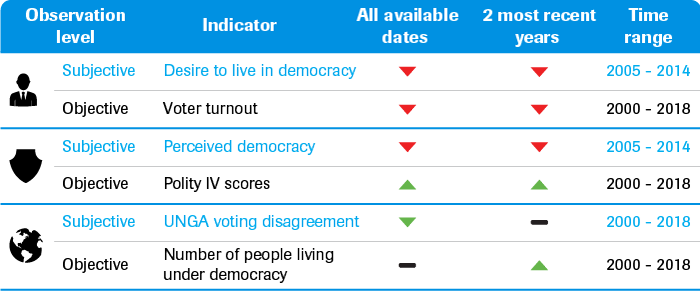

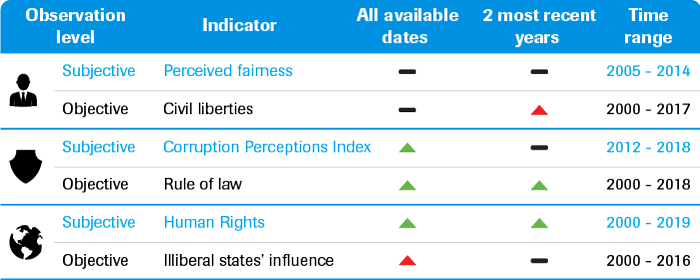

Our analysis of global geodynamics yields a kaleidoscopic picture. The world population has become more prosperous, but inequality has also increased by different measures. Although the world as a whole continues to become more connected, increased connectivity has not necessarily brought people closer together. Societies worldwide have not become more inclusionary, due to a marked increase in identity-driven politics, higher levels of religious restrictiveness, and increases in social hostilities. At the same time, the rule of law has been strengthened and, despite the structural human rights violations in a number of countries, research suggests that human rights protection regimes are improving over time. But despite the growth and spread of democracy over the past two decades, democracy as an institution and especially individual freedoms are under prolonged attack. Civil and political rights have been declining for over a decade now, in both free and unfree countries. At the same time, illiberal governments have undeniably been gaining more influence in the regulation of global affairs. Finally, over the past two decades, the world has become less peaceful and secure because of a growing number of conflicts and conflict fatalities.

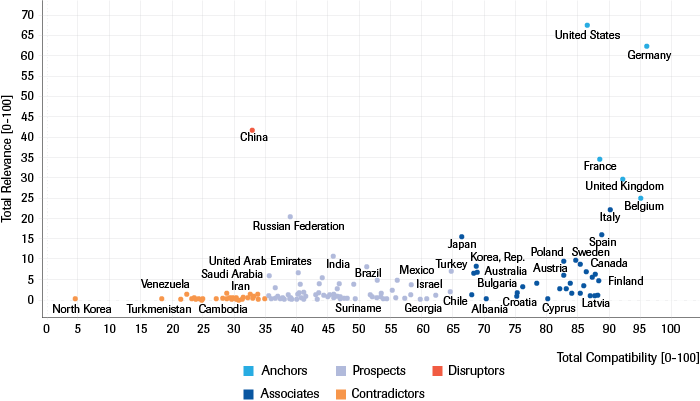

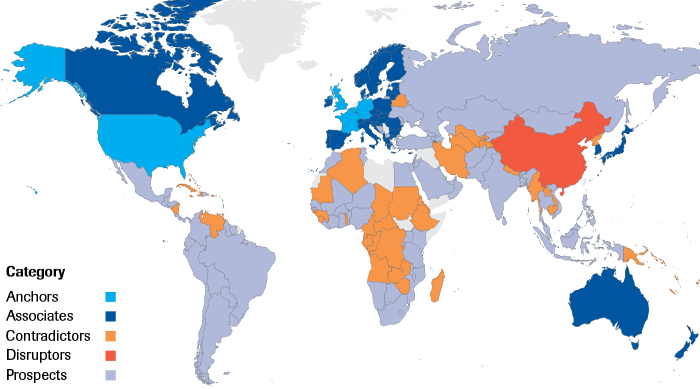

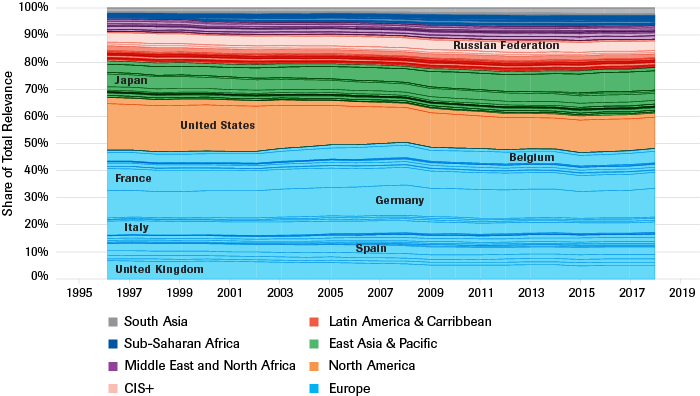

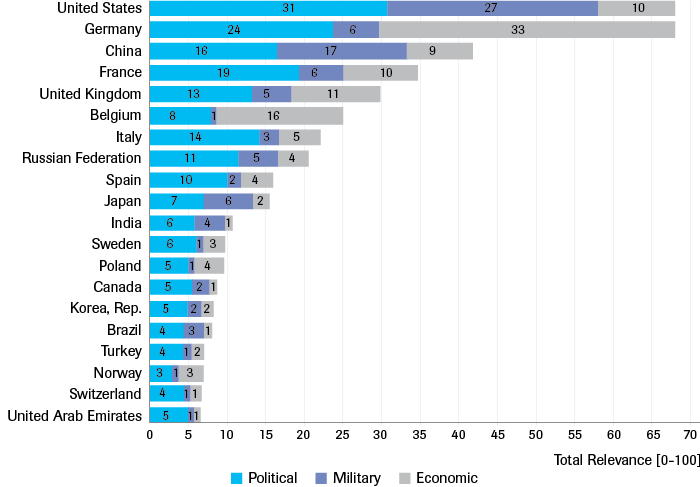

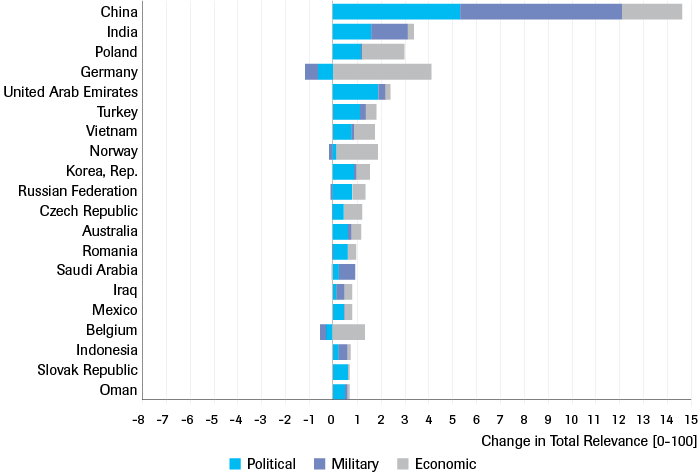

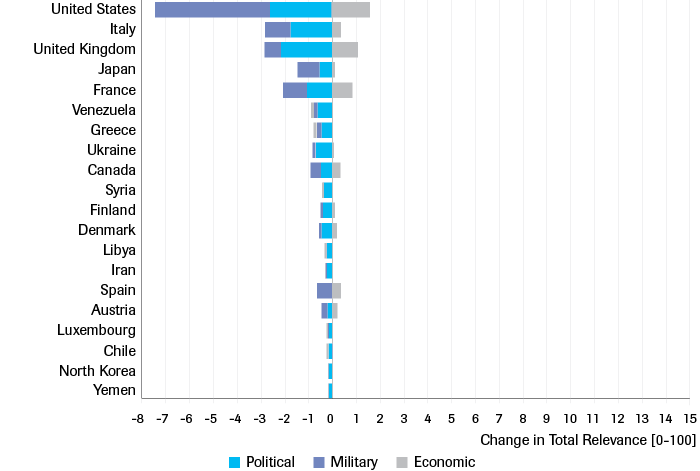

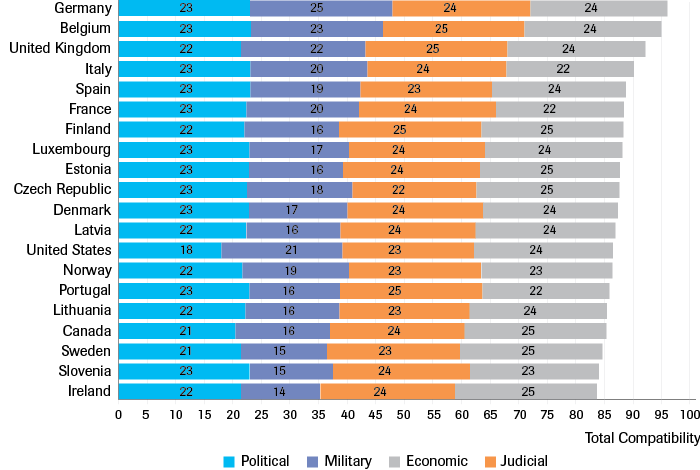

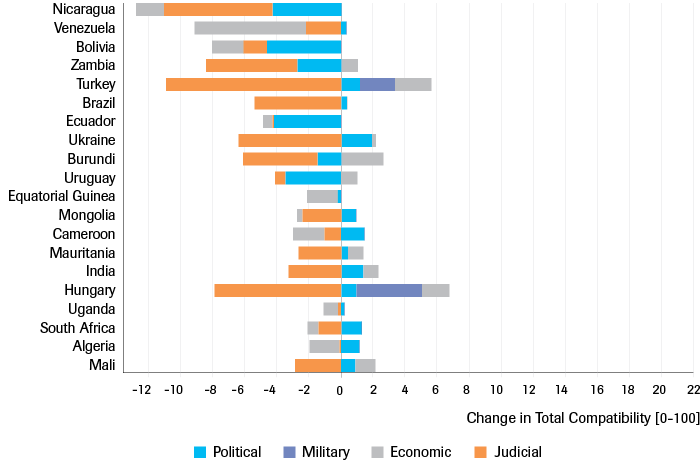

On the world stage, the Netherlands finds itself in a relatively fortunate position. It can count on close allies and partners in its immediate geographic surroundings. Despite ongoing turbulence in the European Union, this regional regime is becoming more relevant for the Netherlands. While the United States and Germany continue to be dominant in Dutch foreign relations, emerging powers have become more relevant as measured along economic, political, and military dimensions over the past decade. China’s ascent economically, militarily, and politically, in combination with the fact that China has a different values system than the Netherlands, implies that, for the Netherlands, China presents both an opportunity and a risk. In addition, a number of middle powers have both become more relevant and moved closer to the Netherlands on important value dimensions, which means that the Netherlands has a range of potential partners to collaborate with in shaping international regimes and rules in this changing context.

Interestingly, a number of other countries in their international security documents not only have a different assessment of the six threats identified in the Integrated Foreign and Security Strategy 2018-2022, but also give greater weight to additional threats. These include climate change and the exploitation and militarization of space. However, as in the Dutch case, most of these documents pay very little attention to the other side of the security coin: opportunities. It is recommended that these two observations be taken into consideration in the design of next year’s activities in the framework of the Strategic Monitor.

Overall, this Strategic Monitor concludes that the tenets of the international order continue to shift. Here it is important to recognize that it is the combination of national and international vectors that converge to undermine bastions of the existing international order, both from within and from without, both bottom-up and top-down.

Increased global competition across military, economic, and political domains goes hand in hand with a persistent erosion of significant aspects of the existing architecture of the international order. Compliance and cooperation are giving way to violation and confrontation across important political, economic, and security regimes, and rules are systematically violated while underlying norms are incrementally hollowed out. There are, however, certainly areas in which international cooperation persists, albeit in the context of voluntary and non-binding initiatives of coalitions of the willing, comprising both national and local governments, and increasingly in partnership with non-state and private actors. The shifts described in this report all take place in an era of rapid technological change, generating a host of new challenges to political and societal cohesion, economic equality, national security, and fundamental human rights.

The increased global competition is having important implications for the nature of threats, including the further fusion of the internal-external security nexus. Borders, physical or otherwise, no longer shield against the dangers posed by external forces. This implies the compression of time and geographical distance. Increased competition is also accompanied by the spillover of threats from one domain to another, with multidomain threats becoming the rule rather than the exception in the context of a connected world.

The dynamics of the US-Sino rivalry will be different from those between the US and the Soviet Union during the Cold War: the former will take place across multiple domains in the context of a more tightly integrated global economy. Some degree of economic protectionism can be expected to remain part of future US policies, alongside a continued strategy of military pre-eminence. Interdependence in different domains can contribute to stability by creating mutual interests, but it can also contribute to the spillover effects that fuel negative spiral dynamics. Economic decoupling into different blocs around the US and China will remove incentives to constrain competition in other domains, most importantly the military domain.

Now, do these developments signify the demise of the existing international order, or do they merely represent a perhaps overdue renovation of regimes within that order that are no longer fit for purpose? The developments suggest a little bit of both: some elements in the existing international order are revised and brought in sync with the global distribution of power; other elements are redesigned from scratch. This leaves the shape of the emerging international order still uncertain, but not entirely unclear during this period of transition.

Based on this year’s reading of the writing on the wall, international relations are expected to feature more outright forms of competition in the economic, military, but also in the ideological realm. The international order is expected to become less liberal in nature and less global in scope, and it will be more fragmented. However, modern means of communication and transportation will continue to facilitate coordination and collaboration that underpin the regimes that make up the order, and vested interests, both public and private, will continue to argue for international coordination and collaboration. Despite ideological differences and competing interests, the urgency of various key international challenges, such as climate change or nuclear proliferation, may yield sufficient pressure on global political leaders to act.

What does this outlook mean for the Netherlands? In light of increasing competition in the context of a decaying order, lopsided dependence on single actors across multiple fields is potentially dangerous. Investing in greater strategic autonomy, not just militarily but also economically and politically, creates greater maneuvering room, which in turn contributes not only to the security and prosperity of the Netherlands but also to the stability of the system at large. Strong collaboration within Europe will remain indispensable, not as an end in itself but as an instrument. However, the changing context and the adaptation of the existing order require greater investment in bilateral relationships that can help achieve Dutch core interests, both inside and outside of multilateral frameworks. In selecting such partnerships and making strategic choices, it is vital to have a clear understanding of the vulnerabilities to which the Netherlands is exposed as well as of the opportunities which the Netherlands can leverage.

The changing context requires not just new partnerships, but also concept development and experimentation with new strategies to keep up with the evolving foreign policy environment. Finally, the changing international context does not mean that we should ignore or under-appreciate our own values. It rather means the opposite. Increasing rivalry between values systems in the world requires that we also make more explicit what we stand for, and which way of life we want to protect and develop, and that where possible we actively use our values as an instrument of power and influence.

Samenvatting

Deze Strategische Monitor 2019-2020, Tussen orde en chaos? De tekenen aan de wand, onderzoekt de structurele lange-termijntrends en actuele gebeurtenissen die de mondiale veiligheidsomgeving vormen en van invloed zijn op de Nederlandse nationale belangen en waarden. Het rapport van dit jaar gaat dieper in op het ontstaan van een nieuwe wereldorde, of beter gezegd, ordes. Het rapport beschrijft en analyseert de belangrijkste veranderingen in de internationale regimes die de internationale orde vormen. In zeven hoofdstukken worden de trends en ontwikkelingen in de internationale betrekkingen en in de veiligheidsomgeving van Nederland onderzocht en geïnterpreteerd, en wordt de balans opgemaakt van de wereld van vandaag en morgen.

In deze Strategische Monitor worden de trends en ontwikkelingen onderzocht ten aanzien van de zes meest urgente veiligheidsbedreigingen uit Wereldwijd voor een veilig Nederland: Geïntegreerde Buitenland- en Veiligheidsstrategie 2018-2022, te weten militaire dreigingen, cyberdreigingen, ongewenste buitenlandse inmenging en ondermijning, bedreiging van vitale economische processen, dreiging van chemische, biologische, radiologische en nucleaire (CBRN) middelen en terroristische aanslagen. De meeste indicatoren voor deze zes thema's wijzen op een verhoogde dreiging voor de komende vijf jaar. De trends en ontwikkelingen in de internationale orde geven een negatief beeld met betrekking tot vier thema's: militaire competitie, hybride conflicten, economische veiligheid en CBRN-wapens. Voor alle vier deze thema's verschuift de mate van samenwerking in de internationale orde naar meer strijd over de normen en regels van de bestaande regimes. De trends en ontwikkelingen met betrekking tot nieuwe normontwikkeling in cyberspace en normconformiteit bij terrorismebestrijding zijn echter beslist positiever van aard. Hier zien we de ontwikkeling van nieuwe normen in cyberspace en meer samenwerking bij internationale inspanningen op het gebied van terrorismebestrijding.

Onze analyse van de mondiale geodynamiek levert een caleidoscopisch beeld op. De wereldbevolking als geheel is welvarender geworden, maar ook de ongelijkheid is toegenomen. En ondanks dat de wereld als geheel meer verbonden raakt, heeft de verhoogde connectiviteit de mensen niet per se dichter bij elkaar gebracht. Wereldwijd zijn samenlevingen minder inclusief geworden door een toename van identiteit-gedreven politiek, een groter aantal religieuze beperkingen en een toename van maatschappelijke polarisatie. Tegelijkertijd is de rechtsstaat versterkt en suggereert onderzoek dat de bescherming van de mensenrechten, ondanks stelselmatige mensenrechtenschendingen in een aantal landen, in de loop van de tijd verbetert. Maar ondanks de groei en verspreiding van democratie in de afgelopen twee decennia, staat democratie als zodanig, en met name individuele vrijheden, onder druk. Politieke rechten en burgerlijke vrijheden nemen nu al meer dan tien jaar af, zowel in vrije als in minder vrije landen. Tegelijkertijd hebben onliberale staten ontegenzeggelijk meer invloed gekregen in de regulering van mondiale aangelegenheden. Ten slotte is de wereld de afgelopen twee decennia minder vredig en veilig geworden.

Nederland bevindt zich op het wereldtoneel in een relatief gelukkige positie. Het kan rekenen op bondgenoten en partners in zijn directe geografische omgeving. En ondanks aanhoudende turbulentie in de Europese Unie wordt dit regionale regime steeds relevanter voor Nederland. Terwijl de Verenigde Staten en Duitsland dominant blijven in de Nederlandse buitenlandse betrekkingen, zijn opkomende mogendheden, gemeten langs de economische, politieke en militaire dimensies, in het afgelopen decennium relevanter geworden. China's economische, militaire en politieke opkomst, in combinatie met het feit dat het land een ander waardensysteem kent dan Nederland, betekent dat China voor Nederland zowel een kans als een bedreiging is. Daarnaast is een aantal midden-machten relevanter geworden en op waardenniveau dichter bij Nederland gekomen, hetgeen betekent dat Nederland een scala aan potentiële partners heeft om mee samen te werken bij het vormgeven van internationale regimes en regelgeving in deze veranderende mondiale context.

Interessant is dat een aantal andere landen in hun internationale veiligheidsdocumenten niet alleen de zes bedreigingen uit de Geïntegreerde Buitenland- en Veiligheidsstrategie 2018-2022 verschillend beoordelen, maar ook meer gewicht toekennen aan andere bedreigingen. Deze omvatten klimaatverandering en de exploitatie en militarisering van de ruimte. Net als in het Nederlandse geval wordt in het buitenlandse veiligheidsdiscours weinig aandacht besteed aan de andere kant van de medaille: de kansen. Aanbevolen wordt om met deze twee observaties rekening te houden bij het ontwerp van de activiteiten van het volgende jaar in het kader van de Strategische Monitor.

Over het geheel genomen concludeert deze Strategische Monitor dat de kaders van de internationale orde blijven verschuiven. Hierbij is het belangrijk te onderkennen dat het de combinatie is van nationale en internationale vectoren die samenkomen om de bastions van de bestaande internationale orde te ondermijnen, zowel van binnenuit als van buitenaf, zowel bottom-up als top-down.

Toenemende wereldwijde concurrentie in de militaire, economische en politieke domeinen gaat hand in hand met een aanhoudende erosie van belangrijke aspecten van de bestaande architectuur van de internationale orde. Naleving en samenwerking maken plaats voor schending en confrontatie in belangrijke politieke, economische en veiligheidsregimes, en regels worden systematisch overtreden terwijl de onderliggende normen geleidelijk worden uitgehold. Er zijn echter ook gebieden waarop de internationale samenwerking stand houdt, zij het vaker in de context van vrijwillige en niet-bindende initiatieven van gelegenheidscoalities, bestaande uit zowel nationale als lokale overheden, en in toenemende mate in samenwerking met niet-statelijke en private actoren. De verschuivingen die in dit rapport worden beschreven, vinden bovendien allemaal plaats in een tijdperk van snelle technologische veranderingen, die een groot aantal nieuwe uitdagingen met zich meebrengen voor politieke en maatschappelijke cohesie, economische gelijkheid, nationale veiligheid en fundamentele mensenrechten.

De toegenomen wereldwijde concurrentie heeft ook belangrijke implicaties voor de aard van de bedreigingen, waaronder de verdergaande samensmelting van de interne en externe veiligheidsdimensies. Grenzen, fysiek of anderszins, beschermen niet langer tegen de gevaren van externe krachten. Dit impliceert een compressie van tijd en geografische afstand. Méér concurrentie gaat ook gepaard met spillover van bedreigingen van het ene domein naar het andere, waarbij multi-domeinbedreigingen zoals hybride conflictvoering eerder de regel dan uitzondering worden in de context van een verbonden wereld.

De dynamiek van de rivaliteit tussen de VS en China zal anders zijn dan die tussen de VS en de Sovjet-Unie tijdens de Koude Oorlog. Eerstgenoemde zal plaatsvinden over verscheidene domeinen in de context van een veel nauwer geïntegreerde mondiale economie. Van het toekomstige Amerikaanse beleid wordt verwacht dat dit gekenmerkt zal worden door een zekere mate van economisch protectionisme, naast een strategie gericht op het behoud van de militaire dominantie. Onderlinge afhankelijkheid in verschillende domeinen kan weliswaar bijdragen aan stabiliteit, maar het kan ook bijdragen aan de spillovereffecten die een negatieve spiraaldynamiek voeden. Economische ontkoppeling in gescheiden blokken aangevoerd door respectievelijk de VS en China zal de prikkels om concurrentie op andere domeinen te beperken, vooral het militaire, wegnemen.

Betekenen deze ontwikkelingen nu de ondergang van de bestaande internationale orde, of vertegenwoordigen ze slechts een renovatie van die regimes binnen de orde die niet langer bij de tijd zijn? De ontwikkelingen suggereren dat het een beetje van beide is: sommige elementen van de bestaande orde worden herzien en gesynchroniseerd met veranderingen in de mondiale machtsverdeling, andere elementen worden helemaal opnieuw ontworpen. Daarmee is tijdens deze overgangsperiode de vorm die de internationale orde gaat aannemen nog steeds onzeker, maar niet helemaal onduidelijk.

Op basis van onze analyse van de tekenen aan de wand, verwachten wij dat de internationale betrekkingen meer openlijke vormen van concurrentie zullen vertonen in de economische, militaire, maar ook in de ideologische sfeer. De internationale orde zal naar verwachting minder liberaal en minder mondiaal van aard worden en zal meer gefragmenteerd zijn. Maar moderne telecommunicatie- en transportmiddelen zullen de coördinatie en samenwerking blijven ondersteunen die ten grondslag liggen aan de bestaande regimes, en actoren, zowel publieke als private, zullen blijven pleiten voor internationale coördinatie en samenwerking. Ondanks ideologische verschillen en tegengestelde belangen, kan de urgentie van verschillende belangrijke internationale uitdagingen, zoals klimaatverandering of nucleaire proliferatie, leiden tot voldoende druk op politieke leiders om op te treden.

Wat betekent dit vooruitzicht voor Nederland? In het licht van de toenemende concurrentie in de context van een veranderende internationale orde is eenzijdige afhankelijkheid van bepaalde actoren potentieel gevaarlijk. Investeren in een grotere strategische autonomie, niet alleen militair, maar ook economisch en politiek, creëert een grotere manoeuvreerruimte, die op zijn beurt niet alleen bijdraagt aan de veiligheid en welvaart van Nederland, maar ook aan de stabiliteit van het mondiale systeem als geheel. Sterke samenwerking binnen Europa blijft daarbij onmisbaar, niet als doel op zich, maar als instrument. De veranderende context en de aanpassing van de bestaande orde vereisen meer investeringen in bilaterale betrekkingen die kunnen helpen Nederlandse belangen te behartigen, zowel binnen als buiten multilaterale kaders. Bij het selecteren van dergelijke partnerschappen en het maken van strategische keuzes is het van vitaal belang om een goed begrip te hebben van de bedreigingen waaraan Nederland is blootgesteld, evenals van de kansen die Nederland kan benutten.

De veranderende mondiale context vereist niet alleen nieuwe partnerschappen, maar ook de ontwikkeling van en experimenten met nieuwe concepten en strategieën om gelijke tred te houden met de veranderende omgeving van het buitenlands beleid. Tenslotte betekent de veranderende internationale context niet dat we onze eigen waarden moeten veronachtzamen. Het betekent eerder het tegenovergestelde. De toenemende rivaliteit tussen waardensystemen in de wereld vereist dat wij ook expliciteren waar wij voor staan, wat wij willen beschermen en willen bevorderen, en dat wij waar mogelijk onze waarden actief inzetten als een instrument van macht en invloed.

1 Introduction

This report focuses on long-term structural developments as well as current events that shape the global security environment and affect Dutch national interests and values. The title of this year’s Strategic Monitor, Between Order and Chaos? The Writing on the Wall, is a reference to the warning of impending discontinuity in the biblical tale of Belshazzar, king of Babylon, as described in the book of Daniel. Belshazzar hosted a lavish feast for more than a thousand dignitaries for which he had used gold and silver goblets taken from the temple in Jerusalem. These goblets were sacred, but the king and his guests drank from them anyway. During the feast a hand appeared and wrote an inscription on a wall. The terrified king called on his magicians to explain what the writing on the wall meant. Only Daniel, the head of the king’s seers, could decipher it. Daniel explained that the writing was a warning to Belshazzar that his days as king were numbered because of his arrogance toward God, and that his kingdom would be split in two. Sudden, structural change such as the end of Belshazzar’s kingdom is a key feature of discontinuity. And the challenge for strategic analysts is to decipher the writing on the wall and to foresee possible future events and developments.

The annual Strategic Monitors have been taking stock of events and developments for almost a decade now. Born out of the Dutch interdepartmental Defense Policy Survey of 2010, the continuous Strategic Monitor horizon-scanning efforts contribute to the government’s long-term strategic anticipation function.[1] In previous iterations, they identified and warned about spikes in great power assertiveness (2013-2014), the risks of conflict breaking out over pivot states (2014), the fragility of the Middle East and the contagious effects of political violence (2014 and 2017), the return of interstate crisis in hybrid guises (2014-2015), and the emergence of a multi-order (2017). In last year’s report, we identified the existence of an interregnum, a transition phase during which the old had died but the new was yet to be born (2018).[2]

This year, we delve deeper into the development of a new international order, or, more precisely, orders. We conceive of the international order not just from the perspective of a liberal world order, but look at it more broadly as being rooted in a collection of international regimes, which are defined as “a set of implicit and explicit principles, norms, rules and decision-making procedures around which the actors converge in a particular area of international relations.”[3] Orders can be global or regional, and they can be ideological (for instance, liberal) or agnostic in nature.[4] The post-Second World War international liberal order, for instance, never encompassed all countries. Certainly during the Cold War period it was a regional order, rather than a global one, except at the very top with the United Nations. Similarly, these orders can be thin or thick in nature: thin orders feature selective elements of engagement on a limited number of important issues (e.g., state sovereignty and arms control); thick orders are characterized by norms and rules that suffuse many aspects of international relations (e.g., trade, human rights, the environment, etc.). The latter is visible in the liberal order that was constructed after the Second World War, came of age during the Cold War, matured further in the 1990s and the 2000s and is now under severe pressure.[5] Orders are rooted in a distribution of power that gives “rise to a relatively stable pattern of relationships and behaviors.”[6] These stable patterns are then institutionalized in the form of coordination arrangements and regimes that are considered legitimate by the most important actors. Orders therefore rest on power and legitimacy.[7]

In times of rapid shifts in the international distribution of power, these stable patterns are undercut by the foreign policy of states dissatisfied with the status quo and with their roles in the system. These states start contesting the role of the leading state, aspiring to a more dominant role in the regulation of international affairs for themselves. This process leads to increased international competition, not just in a narrow, traditional geopolitical sense, but understood more broadly as ‘the attempt to gain advantage, often relative to others believed to pose a challenge or threat, through the self-interested pursuit of contested goods such as power, security, wealth, influence, and status.’[8] Dissatisfaction thus breeds increased competition, which in turn seriously undermines existing regimes and upsets the existing dominant order. It also leads to friction and to crisis and sometimes to conflict and can even escalate to war between contenders and defenders of the status quo.[9]

With the benefit of hindsight, dissatisfaction has been lurking not only under, but also at the surface for quite some time now. For instance, in his 2007 Munich Security Conference speech, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin openly declared that “the unipolar model is not only unacceptable, but also impossible in today’s world.”[10] President Putin denounced “unilateral and frequently illegitimate actions” and asserted that “the United States has overstepped its national borders in every way” because of “the economic, political, cultural, and educational policies it imposes on other nations.” Observing that “the economic potential of the new centers of global economic growth will inevitably be converted into political influence and will strengthen multi-polarity,” he called for a serious rethink of “the architecture of global security” and “a reasonable balance between the interests of all participants in the international dialogue.” Vladimir Putin was not alone in uttering these sentiments. Less antagonistically, but equally determined, China’s President Xi Jinping laid out in 2013 his goal of pursuing “a renaissance of the Chinese nation,”[11] calling for a “new type of major power relations” and, more recently, “a new form of international relations featuring mutual respect, fairness, justice, and win-win cooperation.”[12] Now, as we are entering the third decade of the twenty-first century, European leaders can no longer ignore the impacts of both international and domestic developments on the sustainability of rules and regulations of the international order. At the end of 2019, Emmanuel Macron declared a moment of “unprecedented crisis in our international system,” which “requires new alliances and new ways to cooperate.”[13] And even though the French president views a stronger Europe in many respects as a necessary precondition to transcend this crisis, Macron considers our continent to be “on the edge of a precipice,” with growing societal polarization, considerable disparities between West and East, and a seemingly never-ending Brexit.[14]

The Strategic Monitor annual report monitors, describes, and analyzes the ongoing transition and assesses changes across international regimes that are important tenets of the current international order.[15] The outcome of this transition is far from certain, but it is clear that current events have significant ramifications for the future of international relations, including the rules and regulations guiding state interaction. The international order can evolve in multiple directions at the same time, across different domains of state interaction: it can incline more toward international cooperation, as it would in an ideal notion of a liberal international democratic order, but in parallel it can also evolve toward more international competition. Because of path dependency, developments in the early stages of international order formation have disproportional effects on later outcomes or phases of the order.[16] A better understanding of developments will help policymakers to ‘get there early’ and provide a basis for informed action.[17]

In this context, this report investigates and interprets the developments in international relations and in our security environment, and answers the following question: What have been the main developments in the past ten years with regard to international security, and what trends are in prospect for the next five years? In the following six chapters, we take stock of the world of today and of tomorrow. Chapter 2 looks at trends and developments with regard to the six most urgent security threats from the Dutch policy white paper Worldwide for a safe Netherlands: Integrated Foreign and Security Strategy 2018-2022: military threats, cyber threats, unwanted foreign interference and undermining, threats to vital economic processes, the threat of chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) weapons, and terrorist attacks, and assesses their impact on Dutch national security interests. Chapter 3 examines trends and developments in international regimes based on these same six themes. Chapter 4 turns to geodynamics in the global system and considers structural trends in socio-economic, identity, connectedness, judicial, political, and security domains, in order to provide a snapshot of the state of humanity at multiple levels.[18] Chapter 5 surveys the role and the position of the Netherlands in the world based on an empirical analysis of Dutch foreign relations in the political, economic, security, and human rights realm. Chapter 6 explores global perspectives of important third actors on the six threat themes and identifies differences and similarities. Chapter 7 draws conclusions regarding the threats and international regimes, dominant geodynamics, and the role of the Netherlands. This in turn feeds into an overall assessment of the evolving international order in this period of transition.

The research activities conducted for this year’s Strategic Monitor led to the publication of ten individual in-depth studies in various sub-areas.[19] This report provides an overall framework with which to understand the results of these individual studies (which are of value in their own right) in a more comprehensive context (see Table 1). The ten in-depth studies provide further background, data, analysis, as well as references to the literature used. They thus provide the body of evidence for the insights that are provided here in a more concise form.

| Military Competition in Perspective: Trends in Major Powers’ Postures and Perceptions |

| Cyber security: Parsing the Threats and the State of International Order |

| Hybrid Conflict: Neither War nor Peace |

| Economic Security with Chinese Characteristics |

| CBRN Weapons: Where Are We in Averting Armageddon? |

| Terrorism in the Age of Technology |

| What World Do We Live In? An Analysis of Geodynamic Trends |

| The Evolving Position of the Netherlands in the World |

| In the Eye of the Beholder? An Assessment of Global Security Perceptions |

| Perceptions of Security: How Our Brains Can Fool Us |

To answer the central research question, a wide range of methods and techniques were used to assess the current and future security environment from different analytical perspectives.[20]

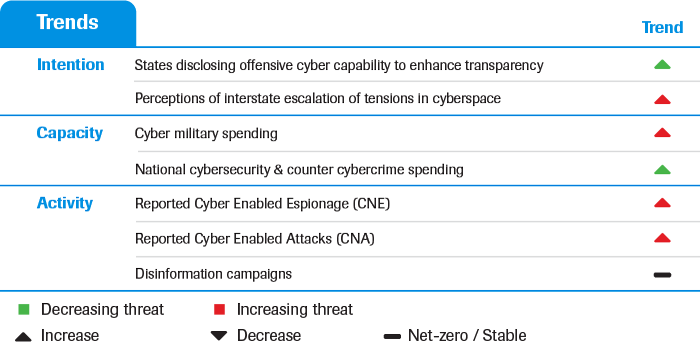

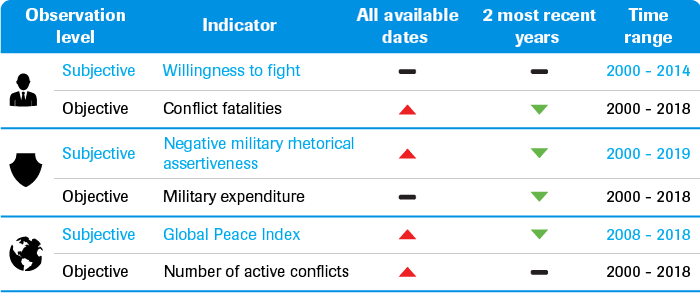

Threat assessment (chapter 2). To analyze the threats, a horizon-scanning method was used, involving a structured investigation of the six threat themes in the literature from government, international organizations, think tanks, and academia, supplemented with information from media and social media. Expressed in a set of indicators for each of the investigated themes, the developments over the last ten years were assessed and further validated using expert judgment. These sets of indicators then served as a basis for making statements on the trends expected over the next five years (up to 2025). Finally, the findings on the threats were linked to the Dutch national security interests to see whether and to what extent they are actually threatened. The Strategic Monitor considers three core interests: 1) national legal order and public security; 2) international legal order; and 3) economic prosperity. These three interests are derived from those used by the various ministries and are consistent with the Constitution, the Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands, and further Dutch legal obligations.[21] In the six respective trend tables in chapter 2, upward trends are indicated with , downward trends with , and stable trends with . These trends are further qualified as being either positive () or negative () in character, based on their impact on the three Dutch national security interests.

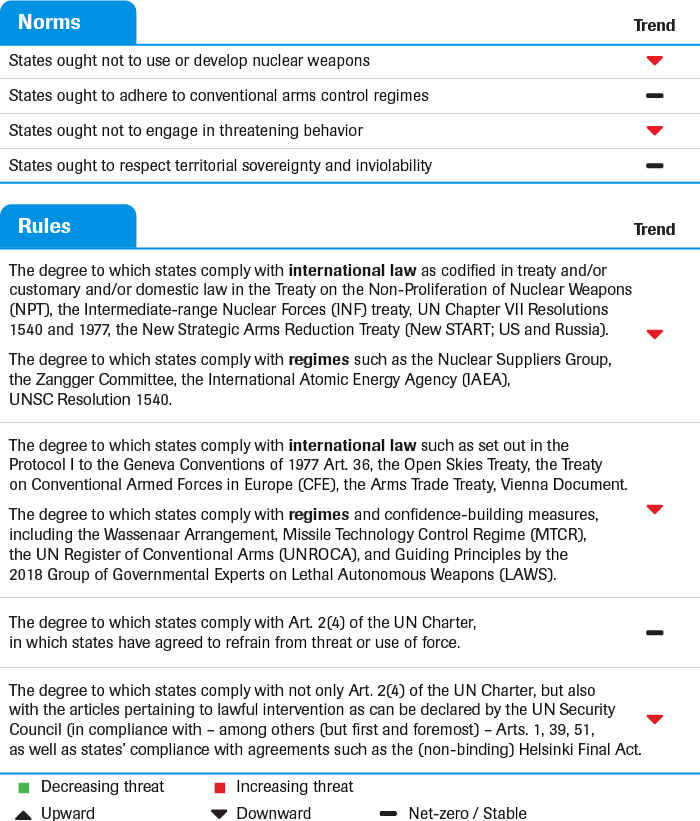

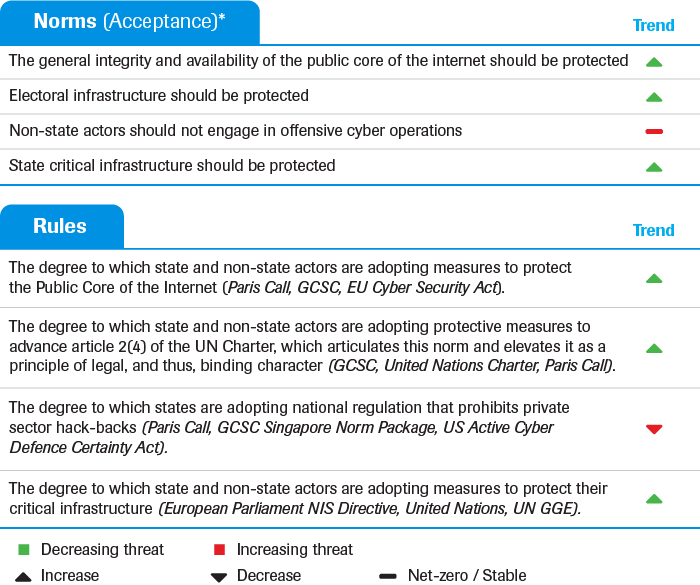

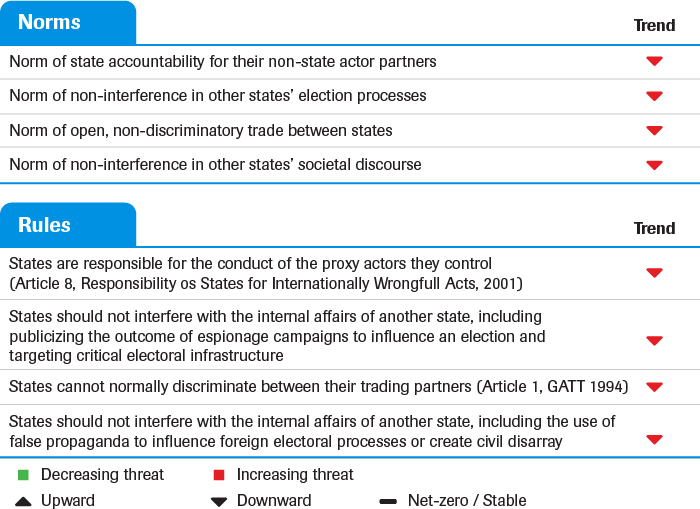

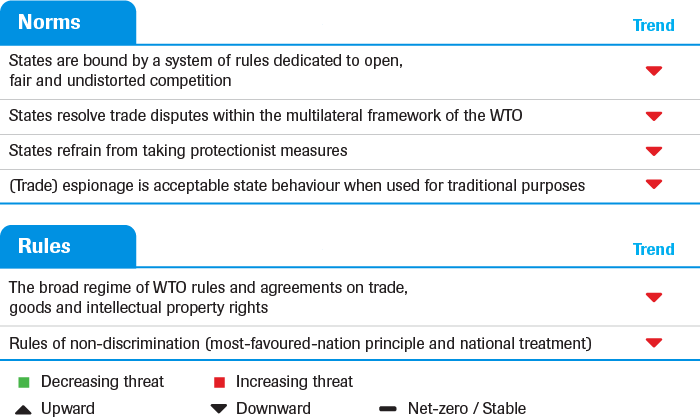

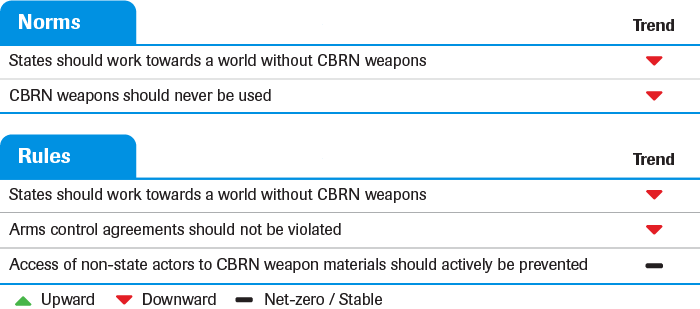

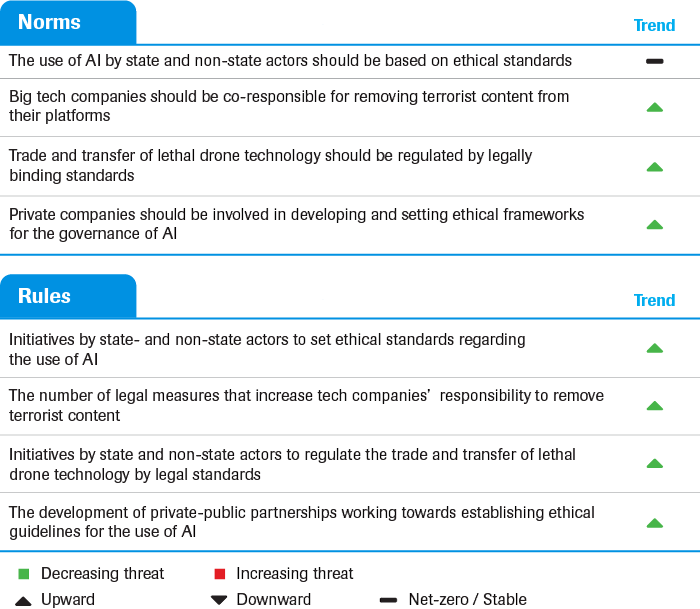

International cooperation and conflict (chapter 3). A comparative approach was used to gauge shifts in the degree of cooperation in the international regimes that together make up an international order for each of the six investigated themes.[22] For each regime, an analysis was made of the extent to which states comply with concrete rules and agreements within the relevant regimes, and with the underlying norms on which those rules and agreements are based.[23] In the six respective trend tables in chapter 3, upward trends are again indicated with , downward trends with , and stable trends with . These trends are again further qualified as being either positive () or negative () in character, based on their impact on the international order encapsulated in these various regimes.

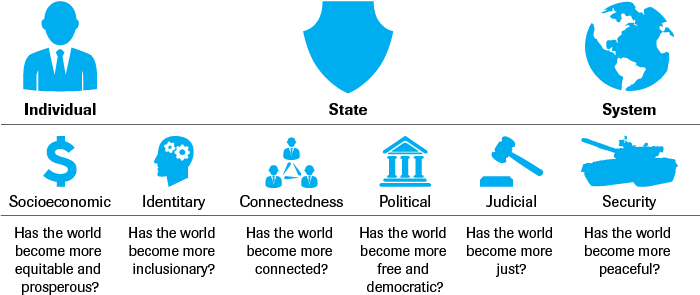

Geodynamics (chapter 4). Next, this report assesses structural developments using a multi-perspective approach. It analyzes an assortment of developments across the socio-economic, identity, connectedness, judicial, political, and security domains at the level of the individual, the state, and the international order. In the six respective trend tables in chapter 4, upward trends are again indicated with , downward trends with , and stable trends with . These trends are again further qualified as being either positive () or negative () in character, based on their assessed impact on international stability and security.

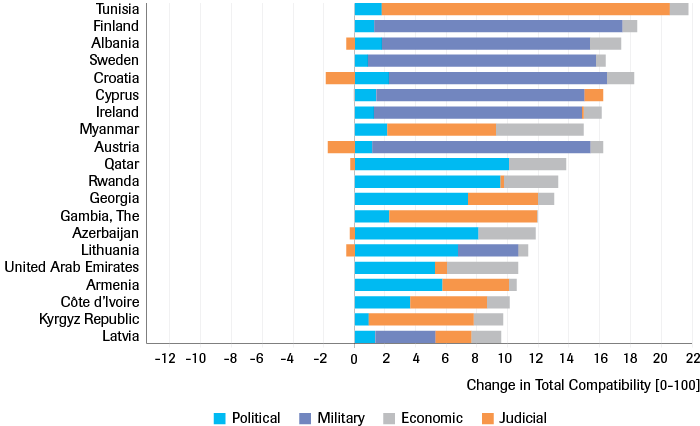

The Netherlands in the world (chapter 5). In order to define the position that the Netherlands currently occupies on the world stage, this report provides an overview of Dutch bilateral relations based on four classic dimensions – economic, military, diplomatic, and ideological – and measures the degree of cooperation in those dimensions based on their associated indicators, such as trade volume, arms trade, state visits, and shared values, using the Dutch Foreign Relations Index (DFRI) developed by HCSS.

An assessment of global security perceptions (chapter 6). To gain a better understanding of the security perceptions of other actors, this report looks at over three dozen post-2016 national security and defense strategies published by other countries and survey-based threat analyses published by world-renowned think tanks and intergovernmental organizations. It examines their perceptions of the six threat themes as well as the international order and surveys which other salient threats and opportunities are identified in these documents.

Chapter 7 offers conclusions based on a synthesis of the findings of the chapters listed above.

2 Development of the Threat

This chapter highlights the most important developments that may threaten our national security in the upcoming years. In this chapter, ‘our’ security refers first and foremost to the security of the Netherlands. Of course, Dutch security interests cannot be seen in isolation from the security interests of Europe, the West, and the international community. This wider context is further elaborated on in chapters 3 and 4. As explained in the introduction, the threat themes discussed in this chapter are the six that were identified as the most urgent in the policy white paper Worldwide for a safe Netherlands: Integrated Foreign and Security Strategy 2018-2022: military threats, cyber threats, unwanted foreign interference and undermining, threats to vital economic processes, the threat of chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) weapons, and terrorist attacks.[24]

2.1 Military Competition

Over the past decade, states have been more actively engaging in military competition. States’ perceptions of the security environment have worsened at a time when military threats are becoming more common in the exchanges between rival states. Global military expenditures have increased only marginally, but some major powers have sharply boosted their defense budgets. States are also reprioritizing the modernization of their armed forces, with considerable funds being allocated to emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and new operational domains such as space.[25] While traditional interstate war remains low in prevalence, the uptick in the number of internationalized intrastate conflicts speaks to increased military competition between states. These findings are corroborated by an analysis of the intentions, capacities, and activities of key states over the past decade (see Table 2), and are further elaborated on below.

2.1.1 Intentions

2.1.1.1 Perceptions of military competition

Military competition is increasingly perceived as an important security priority by major military powers. An analysis of the security and defense strategy documents published by the UK, Germany, France, the US, China, and Russia over the last decade shows a shift toward the identification of interstate competition as a concrete security threat. Both the UK and Germany prioritize interstate competition as a vital security challenge, citing respectively the “resurgence of state-based threats”[26] and Europe’s disadvantage in light of increasing international military competition due to its traditionally limited defense budgets.[27] France recognizes that “the international balance of power is changing rapidly,”[28] stirring greater uncertainty and anxiety. Russia already observed in 2014 that the international order “is characterized by increasing global competition.”[29] The US identifies the “re-emergence of long-term strategic competition” and states its aim of consolidating its military edge vis-à-vis rival powers, most notably China and Russia.[30] China’s 2019 defense strategy, meanwhile, notes that the “international security system and order are undermined by growing hegemonic behavior, power politics, unilateralism, and constant regional conflicts and wars.”[31]

2.1.1.2 Military threats

The intensification of military competition is apparent not only from state perceptions, but also from the use of threatening rhetoric in exchanges between rival states, especially in the context of a number of long-standing disputes. Using data from the Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS), our analysis shows that political and military leaders of permanent members of the UN Security Council have frequently resorted to the use of threatening rhetoric over the past decade with occasional peaks.[32] The highest peak was associated with Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Lower peaks in the period since then can be attributed to the US’ placing of sanctions on North Korea,[33] Iran,[34] and Russia,[35] as well as to the rise in tensions in the South China Sea, and to the Kremlin’s increased engagement in Middle Eastern power politics.[36]

2.1.2 Capabilities

2.1.2.1 Military spending

Overall levels of absolute military expenditures are increasing internationally, albeit not significantly, and not when measured as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). Over the ten-year period from 2008 to 2018, expenditures increased by 13.2%, now amounting to $1.78 trillion in total.[37] The only regions with a significant increase over the past decade are East Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East.[38] At the same time, military expenditures saw a decrease in various other regions. Since around 2015, Europe and the US have started to slightly increase their expenditures again, but in other regions, for instance in Latin America, the downward pattern continues or expenditures remain at a low level (relative to the overall level of military expenditures, which are still by far the highest in North America).

Despite substantial regional variation, military expenditures of key military actors have increased considerably. The most striking example is China, which has doubled its military spending from $120 to $240 billion in the examined period.[39] While official numbers seem to reveal significant recent decreases in Russia’s military spending since 2017 (down by 20% to $66.3 billion), expert reports indicate that a large proportion of real military expenditures are concealed in the state’s budget and, when examined closely, could actually turn out to be as much as 40% higher than before.[40]

2.1.2.2 Defense R&D and procurement

After stagnating between 2012 and 2014, military research and development (R&D) budgets are increasing once again. This is largely due to states’ pursuit of cutting-edge technologies. This is evident in increases in featured states’ R&D budgets, which can be attributed to efforts in military modernization of their armed forces and military capabilities,[41] but also in more specific technology-related investments. Modern technologies’ contribution to increases in military R&D are also evident in the uptick in the number of military assets being launched into space, because of states’ increasing dependence on space assets in the waging of (interstate) wars.[42] This ongoing development is illustrative of a wider trend:[43] as military competition heats up, new domains and frontiers are commanding strategists’ attention.

The US is at the forefront of this trend of increased military R&D spending, focusing on the renewal and modernization of its conventional and nuclear capabilities.[44] R&D funding for the development of modern technologies received the second-largest percentage increase in the US military budget request for 2019, which was 11% higher than its 2018 precursor.[45] Other NATO members are increasingly following suit. Recognition of shortcomings in their military R&D efforts resulted in a 50% increase in allocation.[46] In 2019, NATO members allocated on average 21.7% of their military budget to equipment procurement and R&D, an increase of 1.9% over the preceding year. In 2017, the EU launched the European Defence Fund (EDF), which will make €13 billion available between 2021 and 2027 with the goal of supplementing and amplifying national investments in defense R&D.[47] The trend is also reflected in China’s and Russia’s R&D expenditures, with both states implementing a range of programs to modernize their militaries and upgrade their nuclear capabilities.[48] Russia has committed $700 billion to an armament program that aims to modernize 70% of Russia’s armed forces by 2020,[49] with 59% of Russia’s weapon systems having already been modernized by 2015.[50] Beijing has announced intentions to fully modernize its armed forces by 2035,[51] and is focusing on the development of AI applications for military use.[52] In order to do so, China increased defense spending by 7.5% in 2019, $177,544 billion of which will be allocated to “sustaining, growing, and modernizing” the country’s military.[53]

In this context, the size of investments made by the US and China underscores the role of AI applications in modern-day military competition. European states lag behind these countries in their pursuit of military AI,[54] despite initiatives of individual member states. France, for instance, recently launched a military AI strategy, earmarking €100 million for the development of military AI by 2022.[55]

2.1.3 Activity

Internationalized intrastate conflicts, such as those currently being fought in Libya, Syria, and Yemen, are particular instances of military competition in which states compete for influence in third states’ territories. This type of conflict has increased substantially: it tripled between 2008 and 2018, increasing from six to eighteen. By 2018, such conflicts accounted for 35% of all conflicts (as opposed to 18% in 2008).[56] This trend stands in contrast to the number of state-on-state military conflicts (interstate war), which comes close to zero, and the number of internal (domestic, civil) conflicts, which stays relatively constant.

Unsurprisingly, the Middle East emerges as a hotspot when it comes to internationalized intrastate conflicts, largely as a result of geopolitical opportunities for foreign meddling brought about by the internal conflicts and power vacuums produced as a by-product of the Arab Spring.[57] Furthermore, several states are increasing their military footprint on the African continent, in the context of wider competition for influence. Chinese and to a lesser extent Russian efforts in this region have attracted a lot of media attention.[58] The US is also active, for example through the creation of a new drone base in Niger worth $110 million and the opening of lines of communication with large swathes of North and West Africa.[59] Power competition over the continent is supplemented by assertive actions of middle powers. Among others, the United Arab Emirates and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia have set up a peace deal between Ethiopia and Eritrea while securing the rights to military bases, ports, and trading outposts in those countries in the process.[60] These developments do not neatly fall into the ‘activity’ category of military competition, in that they represent other forms of engagement, but they are nonetheless indicative of increasing awareness of the continent’s strategic importance, both militarily and otherwise.

As geopolitical rivalry is regaining prominence, the threat posed to the Netherlands by military competition has increased significantly – not so much in a direct threat to our territorial integrity, but certainly in an increased risk that the Dutch armed forces, together with the country’s allies, will find themselves embroiled in a future military confrontation.

2.2 Cyber Security

Conflict in cyberspace has intensified exponentially in recent years.[61] Our analysis of the intentions, capabilities, and activities of state actors in this domain suggests that this is unlikely to change in the near future, with greater risks of escalation. Cyber-military and cyber-security expenditures have increased, as have cyber-enabled espionage and computer network attacks. Disinformation campaigns are the new normal in global affairs. States regard threats emanating from cyberspace as a crucial security concern.

2.2.1 Perceptions of interstate escalation of tensions in cyberspace

An increasing number of states identify cybersecurity as either the main or a major security threat in their national security threat assessments.[62] Previous strategies (2006-2013) already acknowledged the relevance of various cyber threats, such as cybercrime, IP theft, espionage, and sabotage. Recent strategies (2015-2019) more specifically single out the threat posed by state actors and state-affiliated or directed cyber operations for offensive purposes, underscoring the relevance of cyberspace for national security. In this context, states have been developing initiatives to address risk management of cyber escalation.[63] Most notably, the application of international law, norms of responsible state behavior, and confidence-building measures (CBMs) have functioned as stability mechanisms that establish ‘rules of the road’ for responsible state behavior in cyberspace. Over the last couple of years, the cyber-strategic postures of leading states have evolved to include the more offensive deterrence by punishment, complementing deterrence by denial, entanglement, and normative stigmatization. This is illustrated, for example, by the US doctrine of “persistent engagement” that is designed not only to thwart adversary cyber operations by continuously anticipating and exploiting their vulnerabilities, but also to reinforce deterrence by raising the costs for adversaries.[64]

2.2.2 States disclosing offensive cyber capabilities to enhance transparency

The lack of transparency in cyber capability deployment, and even in the method of operations or intended effects, renders the task of assessing a state’s intentions, capabilities, and activities difficult.[65] Based on an open-source analysis of public statements, we observe a growing number of states disclosing their offensive cyber capabilities. The US National Security Agency puts the current number at thirty.[66] It signifies the progressive militarization of cyberspace. To some degree, it also points toward efforts at increasing transparency, which is necessary for the development of rules and norms to harness competition in this domain.

2.2.3 Assessing spending on cyber capabilities

Government funding to enhance cybersecurity can be perceived as either heightening or reducing the threat level in this environment, depending on whether the spending is directed toward defensive or offensive measures. We therefore distinguish between ‘national cybersecurity and counter cybercrime spending’, which is defensive by nature, and ‘cyber-military spending’, which includes both offensive and defensive capabilities. A review of open-source documents and budgets of eight Western countries shows current government spending has increased in both categories.[67] The US remains at the forefront of cybersecurity spending, with countries such as France and the UK following suit. The rise in investment in defensive measures is also indicated by the creation of dedicated agencies and departments that focus on cybersecurity. As a reflection of the increase in states disclosing offensive cyber capabilities, cyber-military spending is also rising. The US leads this trend, with significant portions of the 2019 annual budget being allocated to the US Cyber Command.[68] Under both the Obama and Trump administrations, the capabilities of the US Cyber Command have expanded through an increase in personnel, a greater operational mandate, and enhanced technical capabilities.[69] Although overall military spending on cybersecurity is significantly lower in the other examined countries, their investments in offensive cyber capabilities have also grown.

2.2.4 Cyberespionage

In cyberspace, states may hide under a veil of anonymity to engage in malign cyber activity, in order to achieve strategic and operational gains. States have been more aggressively engaging in various activities: computer network exploitation, which includes cyberespionage; computer network attacks, which include attacking the availability and integrity of data and ICT systems; and disinformation campaigns. While attribution remains complicated, targeted states are increasingly naming and shaming malign actors.[70] The past ten years saw a considerable rise in reported instances of cyberespionage, according to data from the Cyber Operations Tracker of the Council on Foreign Relations.[71] China in particular is reported to be engaging in intellectual property and advanced military technology theft through its PLA Unit 61398 as well as other government units.[72]

2.2.5 Computer Network Attacks

Similarly, Computer Network Attacks are increasingly prevalent. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the number of reported significant cyber incidents increased seven-fold between 2008 and 2018.[73] Denial of service, domain name system (DNS) hijacking campaigns, malware attacks, phishing, and ransomware attacks seek to damage, destroy, or disrupt computers and/or computer operations,[74] with direct or indirect negative impacts on states.[75] Notable Computer Network Attacks include: Stuxnet (2010); the attack on Saudi Arabia’s oil infrastructure in 2012; attacks against the Ukrainian power grid (2015); North Korea’s targeting of Microsoft Windows computers (WannaCry, 2017); and Russia’s release of NotPetya (2017).[76]

2.2.6 Disinformation campaigns

Cyber-enabled disinformation campaigns are increasing too. Although there is no comprehensive data source providing reliable data for the past decade, an abundance of studies and reports highlight how states are engaging in comprehensive disinformation campaigns to influence public perception and erode trust in democratic systems.[77] According to the Oxford Internet Institute, the number of states featuring active disinformation campaigns more than doubled from 28 to 70 between 2017 and 2019. At least seven states (China, India, Iran, Pakistan, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela) have executed influencing campaigns in other countries.[78] Recent technological developments in this field – including the rise of ‘deep fakes’, i.e., hyper-realistic, difficult-to-debunk fake videos – are expected to further affect the nature and impact of disinformation campaigns.[79] At the same time, efforts to counter disinformation campaigns are increasing, especially in European countries.[80] Overall, our analysis of perceptions, intentions, capabilities, and activities of states in the cyber domain warrants the conclusion that cyber conflict is intensifying, and is likely to continue to do so in the years to come.

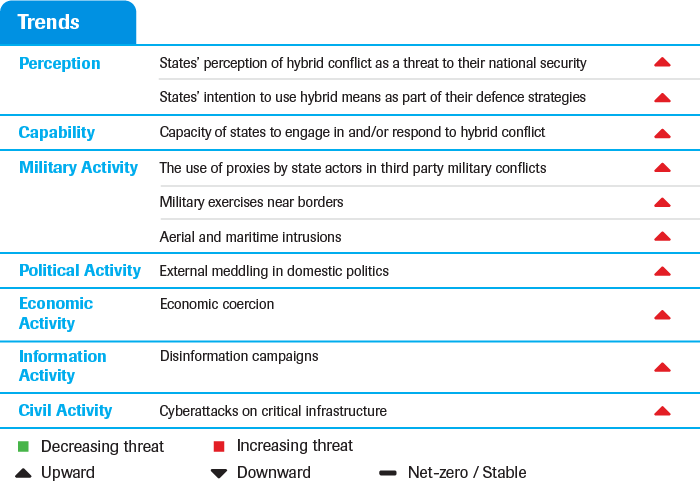

2.3 Hybrid Conflict

Hybrid conflict, understood as “conflict between states, largely below the legal level of armed conflict, with integrated use of civilian and military means and actors, with the aim of achieving certain strategic objectives,”[81] has become much more prominent over the past decade. States are increasingly deploying hybrid tactics, often in a subtle and pervasive form to hamper detection, accountability, and retaliation. These tactics include the use of proxy actors in third-party military conflicts, the deployment of military exercises near borders, intrusions into aerial and maritime territory, the exertion of influence over foreign democratic processes, the use of economic coercion, the proliferation of disinformation campaigns, and the execution of cyberattacks on critical infrastructure. Our analysis of intentions, capabilities, and activities in this sphere paints an overall bleak outlook (see Table 4).[82]

2.3.1 States’ perception of hybrid conflict as a threat to national security

Comparative assessments of security and defense strategies between 2008-2009 and 2018-2019 reveal that states increasingly recognize hybrid conflict as a threat to national security.[83] The US currently identifies cyber conflict, disinformation campaigns, and economic coercion, explicitly designating China, Russia, and Iran as culprits.[84] Germany and the Netherlands are particularly concerned about cyber threats and information warfare. Germany moved from signaling a “digital lack of security”, but without mentioning “hybrid”, in 2008 to explicitly identifying hybrid conflicts as a security risk in 2018.[85] The Dutch Integrated International Security Strategy (2018) illustrates hybrid conflict with threats such as foreign interference through disinformation, cyberespionage, sabotage, and foreign funding.[86] Over a ten-year period, the UK exhibits a heightened awareness of hybrid threats in the cyber and political domain.[87] But the recognition of hybrid threats is not exclusive to Western countries. Russia points out risks posed by external manipulation and subversion, noting that “[t]he intensifying confrontation in the global information arena caused by some countries’ aspiration to utilize informational and communication technologies to achieve their geopolitical objectives, including by manipulating public awareness and falsifying history, is exerting an increasing influence on the nature of the international situation.”[88] China, too, makes reference to hybrid threats emanating from the US, through the use of sanctions and political provocation.[89] In contrast to its 2008 equivalent, China’s 2019 defense white paper mentions hybrid threats, including the rise of cyber-related threats, the potential use of sanctions against companies and academics, and other states’ financial support of Tibet’s freedom movement.[90]

2.3.2 States’ intention to use hybrid strategies

Having pioneered strategic innovation in this sphere over the past decade, Russia emphasizes “cross-domain coercion” as part of its strategic deterrence posture, which combines both military (conventional and nuclear) and non-military capabilities and measures.[91] China’s latest defense strategy reserves “the option of taking all necessary measures” to safeguard China’s national sovereignty, security, and interests.[92] Overall, such intentions are expressed to a greater extent than ten years ago,[93] although Western states thus far have predominantly framed this within a defensive context of countering hybrid activities. The cyber domain represents an exception to this tendency, as states increasingly disclose their intentions to use offensive cyber measures against other states.[94] The UK, for instance, stresses its willingness to use armed force to defend itself from cyberattacks and to protect its networks, if attacking the networks of the attacker is necessary.[95]

2.3.3 States’ capabilities to engage in and/or respond to hybrid conflict

States are increasingly investing in government agencies that engage in or respond to hybrid conflict. China, Russia, the US, France, Germany, the UK and the Netherlands have all created, invested in and widened the scope of such government agencies over the past ten years. In addition to employing public organizations and agencies, many states carry out hybrid operations through non-state actors or covert units.[96] Russia’s capabilities are illustrated by the increased role of the Russian Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces (commonly referred to as the GRU), as well as the Russian Internet Research Agency, which is involved in “bot farms” and disinformation campaigns.[97] In China, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Strategic Support Force (home to Unit 61398, among others) has been mentioned by experts as a hybrid-focused force, with tasks including information warfare and cyber operations. China’s whole-of-government approach to conflict and security means that several government agencies, not specifically designated as ‘hybrid’ actors, may play a coordinated role in these activities.[98] The US Cyber Command is another example of a military-focused agency with an important role in hybrid conflict, as exemplified by a cyberattack the Command undertook in Iran during July 2019.[99] In Europe, for instance, the Netherlands has established a Counter Hybrid Unit.

2.3.4 The use of proxies by state actors in third-party military conflicts

Just as in the Cold War, states are engaging in proxy conflicts.[100] Proxy conflicts arise when states “instigate or play a major role in supporting and directing a party to a conflict,” but do only a small portion of the fighting themselves.[101] These conflicts allow states to secure ideological and/or strategic objectives without putting a significant number of their own troops in harm’s way. Proxy wars also offer the opportunity to test and showcase new weapon systems, facilitating a learning process that would otherwise only be available within the context of interstate conflicts.[102] Proxy wars can be understood as a form of hybrid conflict, not only because they are also a form of gray zone operations – as can be inferred from states’ systematic denial of involvement in these conflicts[103] – but also because there are well-documented instances of these activities being employed to secure objectives that fall outside these conflicts’ direct geographical scope. In addition to the earlier-reported steep increase in the number of internationalized intrastate conflicts – which with eighteen conflicts account for 35% of all conflicts in 2018 (as opposed to 18% in 2008)[104] – the number of actors involved in these proxy conflicts has increased from an average of 3.7 actors per proxy conflict in 2008 to 5.8 actors in 2018.[105] The upward trend in the use of proxy forces extends into cyberspace, where states increasingly rely on cybercriminals as extensions of state power.[106]

2.3.5 Military exercises near borders

Military exercises near the borders of actual or potential adversaries are a well-established practice, meant to intimidate without crossing the threshold into conventional conflict. Without any effective confidence- and security-building measures (CSBMs) in place, these military exercises have the potential to exacerbate instability and lead to escalatory retaliations. Military exercises near borders have increased in number and in magnitude over the last ten years.[107] Especially over the last five years, after the Crimea Crisis, they have become both larger in scale and more regular in occurrence, both in Europe and in Asia.

2.3.6 Aerial and maritime intrusions

Similarly, aerial and maritime activities that stay below the threshold of actual confrontations seem to be increasing. Intrusions are exercises that deliberately and provocatively enter other states’ territories (or threaten to do so). Measurements reveal a slight upward incline in interceptions of Russia’s aerial activities over NATO territory, but also a more striking trend toward indirect interferences that provokingly threaten, but do not violate, NATO territory. Similarly, expert analyses reveal that, since 2008, Chinese military naval activities have increased in the East and South China Sea.[108] According to the Japanese Foreign Ministry, the number of vessels within Japan’s territorial waters and the contiguous zone rose in 2012 and has since remained consistently high.[109] The number of vessels in the contiguous zone is approximately twice as high as that witnessed in territorial waters, speaking to the notion that most Chinese maritime activities have not directly violated littoral states’ territorial integrity, but have rather taken a more blurred approach, typical of the hybrid domain. In 2017, this number spiked considerably, which can be linked to a more aggressive approach taken by China in the first half of 2017 when it departed from sending only ships into the disputed territories and began also to use unmanned aircraft.[110] Overall, the Chinese are increasingly employing both military and paramilitary law enforcement ships in order to patrol and curb the influence of other actors in the waters.[111]

2.3.7 Political activity

Exploiting the networked nature of information societies, political interference has surged. Meddling activities include, but are not limited to, disinformation campaigns, cyberattacks, and economic coercion. As reported in chapter 2.2, disinformation campaigns have greater reach and impact than ever before.[112] In addition to well-reported cases, such as the 2016 US election interference, political meddling as a hybrid tactic occurs on a global scale.[113] In Western Europe, cyberattacks and disinformation campaigns are more common than elsewhere,[114] whereas countries in the Western Balkans tend to be victims of economic coercion and corruption.[115] Russia’s activities include cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, and economic coercion such as exploiting its energy resources.[116] Russia also uses proxy organizations, such as the Wagner Group, to exercise pro-Kremlin influence in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. China also embarks on information campaigns, as well as engaging in persistent state-sponsored espionage and the fostering of economic dependencies on a global scale, which it can exploit for political purposes.[117]

2.3.8 Economic activity

States are increasingly resorting to coercive economic measures to achieve their political objectives by exploiting economic vulnerabilities and dependencies.[118] An analysis of Global Trade Alerts reveals a massive surge in ‘harmful measures’ associated with economic coercion between 2008 and 2018. In addition, economically coercive events, as reported in the Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS), such as sanctions, boycotts, and embargos, have also increased considerably. This has been clearest in recent years, with the US becoming much more assertive. A spike occurred in 2018, with US measures aimed at China and Chinese state-owned enterprises, Iran and Iranian officials, Russia, and Turkey.[119]

2.3.9 Information activity

As reported in chapter 2.2.6, disinformation campaigns have become much more prevalent, with the explicit intent to manipulate democratic discourses and stir up societal disarray, polarization, and impact on democratic processes. The reach and impact of recent campaigns have increased through strategic and technological innovation.[120] Disinformation campaigns vary by perpetrator, methodology, and motivation. While Western understanding of modern disinformation is predominantly shaped by Russian activities, an increasing number of states are also active in this domain. India, Iran, North Korea, and Saudi Arabia, amongst others, are developing capabilities in information manipulation.[121] China is also becoming more active in this field.[122]

2.3.10 Cyber activity

As reported in chapter 2.2, the number of cyberattacks on states’ critical infrastructure has also increased sharply over the past ten years. Examples include the 2012 cyberattack on the Saudi national oil company Saudi Aramco and two attacks perpetrated in 2015: the ‘WannaCry’ ransomware attack on the UK’s National Health Service and the attack on Ukraine’s energy distribution company. In 2018, the US Government warned that actors associated with the Kremlin were conducting cyber reconnaissance on energy, nuclear, water, and other critical infrastructure sectors in the US, possibly in preparation for targeted attacks. An assessment of the most significant cyber incidents reveals that most attacks on critical infrastructure were state-on-state in nature.[123] The most frequent actors to target other states’ critical infrastructure were Russia, China, and Iran, closely followed by North Korea. The main targets of such cyberattacks have been the US, South Korea, India, and Ukraine.[124] Many of the reported events do not take place during a military conflict, but in the gray zone.[125]

Overall, our analysis corroborates the conclusion that hybrid threats have proliferated within the international security environment. States are engaged in a range of hybrid activities and are gearing up for competition in the gray zone. In the military domain, the increased prevalence of hybrid conflict is substantiated by rising trends in the use of proxy actors, the frequency and scale of military exercises near borders, and the number of aerial and maritime intrusions. External meddling in domestic politics has become more widespread. Economic coercion is becoming more common. Hybrid strategies also extend to the information and cyber domains, where the dissemination of false information and cyberattacks on critical infrastructure have increased considerably.

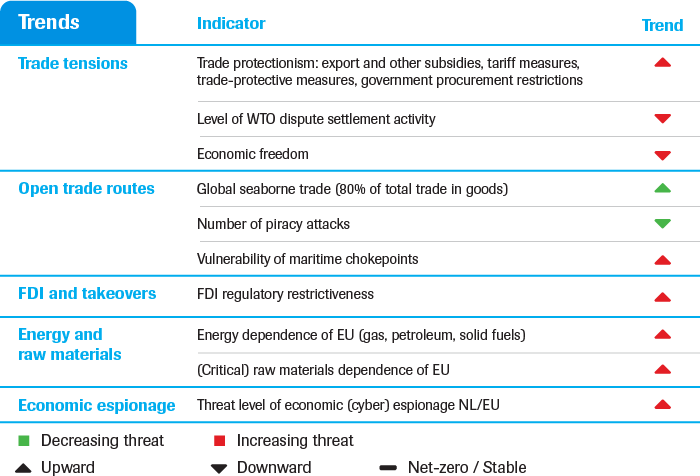

2.4 Economic Security

Geopolitical competition is currently reshaping the global economy, and economic power and instruments are increasingly used for political purposes. Simultaneously, the fast-changing and increasingly complex contemporary geopolitical context has shifted increasing attention to economic security. It is developments like these that illustrate that economics, politics, and geopolitics have become more interwoven. Hence, it is not surprising that economic security has been receiving increased attention from both European and Dutch policymakers. In the field of economic security, the results of our horizon scan give cause for concern. Even though some positive developments can also be witnessed, there are increasing concerns, in particular when it comes to trade tensions and economic espionage. Table 5 provides an overview of the different threat-related trends and developments in the field of economic security.

2.4.1 Open trade routes

Conflicts in countries surrounding the Suez Canal and the influence of Russia and China in the region potentially affect trade routes. For example, unrest in the Horn of Africa could threaten navigation in the southern entrance to the Red Sea, thereby possibly affecting access to Egypt’s Suez Canal. Moreover, Egypt has been making diplomatic overtures to Moscow and Beijing, as the US’ involvement has diminished. Egypt and China have already signed deals worth $18 billion as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In addition, Egypt recently signed deals with Russia to establish a Russian industrial zone around the Suez Canal. Chinese and Russian influence could potentially endanger access to this important trade corridor.[126]

Another potential threat originates from pirate attacks and armed robberies in West Africa. After a period of decline, the number of pirate attacks and armed robberies has recently been on the rise. West Africa has overtaken the Horn of Africa as Africa’s piracy hotspot. According to the International Maritime Bureau’s annual report, pirate attacks and armed robberies rose worldwide between 2017 and 2018, with a surge of attacks off West Africa, despite declining numbers in other parts of the world. Petro-piracy in particular is a growing risk off West Africa and can affect oil supplies to the EU.[127]

2.4.2 FDI and takeovers

China has become increasingly active with foreign direct investment in the EU, enhancing its political influence. Greece, Portugal, and Malta have already signed deals with China, in sectors ranging from energy to transportation, in addition to a significant Chinese presence in insurance, health, and financial services. Italy – the first G7 member and the third-largest EU economy – has signed deals worth €2.5 billion. That figure could potentially rise to €20 billion, since the two countries have pledged closer economic cooperation, particularly in the fields of connectivity, (energy) infrastructure, and trade. In its wake, several EU member states signed an agreement within the BRI framework. Even though these investments are relatively small, and projects may fail, the political significance may be great. In other countries, similar investments have led to the emergence of debt traps or divergent voting in international organizations. In the future, the EU will have to deal with China on other issues as well, such as export controls and defense cooperation in the sphere of stability missions.[128]

2.4.3 EU dependency on energy and raw materials

With the construction of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline at an advanced stage, the debate surrounding the commercial and geopolitical implications is heating up, as the EU is becoming more aware of the risks. The debate highlights tensions within the EU and NATO. Germany’s role as an advocate of Nord Stream 2 has been heavily criticized, by Poland, for example. The European Parliament adopted a resolution urging Germany to halt the project. Proof of heightened geopolitical tensions can also be found in US policy, with preparations to sanction EU firms (co-)financing Nord Stream 2. This could potentially also hurt Dutch firms. Another source of debate is the Baltic region. In January, Russia launched a liquid natural gas (LNG) power plant in order to make its Kaliningrad exclave self-reliant if NATO members unplug the power grid. The exclave is at risk of becoming the stage for a new gas ‘Cold War’.[129]

An area particularly prone to geopolitical tensions is the Arctic region, where both China and Russia are expanding their presence. China has announced that it will start building its first airport in the Arctic. Russia has given the state corporation Rosatom a leading role in the development of the Northern Sea Route. The company recently opened a base in Murmansk to monitor and regulate ship traffic. Russia is also renewing and reactivating Cold War military infrastructure in the Arctic. China and Russia are increasingly seeking cooperation in the region. China is seeking to integrate its ‘Polar Silk Road’ – a predominantly Sino-Russian partnership – into the greater BRI. A major component is the development of joint ventures with Russia in resource extraction, including fossil fuels and raw materials. China will likely gain more from their collaboration, as Russia’s ventures are too reliant on stable oil prices.[130]

The energy sector has also become increasingly vulnerable to cyber threats. In addition, AI-based malware will likely usher in a new era of threats to the energy industry, allowing hostile actors to wreak havoc on a scale hitherto unknown. AI-driven malware can be employed with unprecedented accuracy and is very hard to stop.[131]

2.4.4 Economic espionage

Although China has been conducting espionage for years, it is currently ramping up its espionage activities. In particular, the number of corporate cyberattacks outside China has recently soared and costs have risen accordingly. The Netherlands’ General Intelligence and Security Service (AIVD) has called China “the biggest threat when it comes to economic espionage.”[132] China is particularly interested in Dutch companies that operate in the high-tech, energy, maritime, and life sciences and health sectors. A particularly concerning development is that China’s Ministry for State Security (MSS) is working more closely with Chinese enterprises and uses cover organizations such as universities, trade associations, and think tanks. China has become more aggressive and seems to care less if it gets caught or if people go to jail. It also uses non-cyber means of espionage, such as recruiting employees to steal information or stealing specific technological inventions (for example, genetically modified rice seeds). These developments show how active China has become in the field of espionage.[133]

Overall, it can be said that our economic prosperity – essentially dependent on preventing trade tensions, keeping trade routes open, ensuring the supply of energy and raw materials, and countering economic espionage – is under threat, not least from China. Moreover, these threats to free trade, access to energy and raw materials, and our competitive advantage in the fields of knowledge and technology, are expected to intensify over the coming years.

2.5 CBRN Weapons

Over the past few years, chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) weapons have returned to the forefront of the international political agenda. In particular, nuclear weapons and the discussions surrounding the related arms control regimes have been the center of attention. Not surprisingly, the results of our horizon scan are not very reassuring when it comes to the current trends and developments regarding CBRN weapons. Most of the threat-related trends in this field show a negative dynamic, which means that the threat is expected to become even more severe in the coming years (see Table 6).

2.5.1 Arsenals

A key trend in the CBRN domain is the fact that all nuclear-armed states are investing heavily in the modernization of their nuclear arsenals as well as in developing new missile technologies. Some of them are producing, and maybe even testing, low-yield nuclear weapons. The production of these weapons is controversial, as several experts argue that, with their lower (political) threshold for use, they raise the escalation potential. Moreover, experts speak of a growing arms race between the great powers over hypersonic missiles. These missiles raise the escalation potential, due to the limited response time available to political and military actors when they are deployed, and because of the difficulty of distinguishing between nuclear-armed and conventionally armed ballistic and cruise missiles.[134]

A second trend is that developments in biotechnology raise the risk of (terrorist) attacks with biological agents. Techniques such as Clustered Regulatory Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) allow for unprecedented precision in gene editing. While such techniques can be used to cure diseases, they can also be used to create new diseases or to modify existing ones.

A third trend that warrants mentioning here is the dual-use nature of new pharmaceutical applications, which makes future verification of arms control agreements and export control regulations more difficult.[135]

2.5.2 Policies

Non-state actors have increased access to knowledge and technologies essential to the production of biological and chemical weapons. Controlling the spread of emerging technologies, such as additive manufacturing, 3D printing, and AI, which can be used to manufacture biological weapons, is difficult due to their dual-use nature. A similar trend can be witnessed in the field of chemical science. The lack of knowledge on the part of policymakers and the limited coverage of current regulatory regimes make it difficult to address the risks.[136]

Recent trends highlight the development of new weapon systems that make the distinction between nuclear and conventional weapons more diffuse. These more advanced systems make it difficult for states to determine whether an incoming weapon has a nuclear or conventional charge. This results in an increasingly blurred line between nuclear and conventional weapons, which could potentially lead to a nuclear war, as misperceptions may occur more easily. This risk is even more worrisome considering the entanglement of nuclear and conventional command and control (C2) systems.[137]

Overall, our analysis of the trends and developments related to both arsenals of and policies regarding CBRN weapons warrants the conclusion that this particular issue will likely stay at the forefront of the international political agenda for years to come.

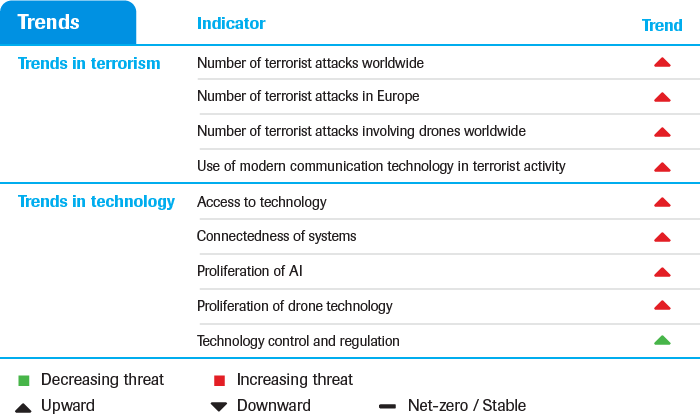

2.6 Terrorism