Introduction

This Global Security Pulse examines trends within hybrid conflicts, understood as "conflicts between states, largely below the legal level of armed conflict, with integrated use of civilian and military means and actors, with the aim of achieving certain strategic objectives."[1] The trends are assessed through a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the intentions, capabilities and activities of state actors, as well as of the norms and rules relevant to hybrid conflict. Its principal conclusion is that the international security environment is increasingly subject to hybrid threats, often in a subtle and pervasive way that impedes fast detection, accountability and retaliation. Hybrid threats and hybrid conflict are typified by their complexity, ambiguity, multidimensional nature and gradual impact. These characteristics pose a challenge to effective response measures and therefore to the international order.

States have ample reason to be concerned about hybrid threats and hybrid conflict. Although at their core hybrid tactics are tactics old as time (military posturing, spreading propaganda and the use of economic measures are well established military strategies), the availability of a diverse and sophisticated set of (technological) tools enhances the impact, reach and congruence of hybrid threats. Paired with the reluctance of states to engage in conventional war due to nuclear, economic and political deterrence, this means that hybrid conflict constitutes an increasingly desirable strategy for states to achieve their political goals.[2]

This report consists of two sections. The first section analyzes a set of indicators used to measure hybrid conflict over a time period of ten years. A spectrum of hybrid activities is measured and categorized for the relevant domains – military, political, economic, information and cyber – to show developments over that period. The second section reflects upon the challenges hybrid threats present to the international order. This is done by analyzing the adherence to norms and rules in this evolving field. The overall conclusions are given in a final chapter.

Trends in Hybrid Conflict

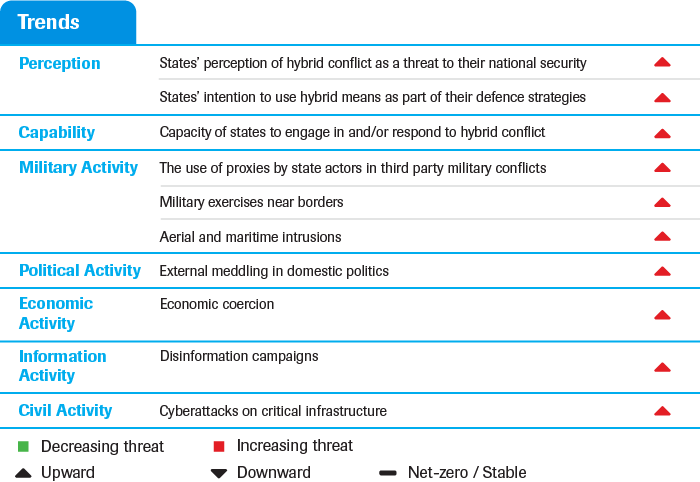

Table 1 provides an overview of the indicators that, taken together, give a general image of the developments and trends in hybrid conflict. The various categories and corresponding indicators are elaborated upon throughout this paper.

The states examined for the Perception and Capability trend assessments were selected based on their relevance to the Dutch threat environment, the availability of open source defense strategies and the objective to cover a range of different actors. The resulting set comprises the Netherlands (in order to gauge the perceptions and capabilities of the referent state), close allies France, Germany, the UK and the US, and two major powers China and Russia. The trends under Activities were analyzed according to a broader scope, although many examples again pertain to the state actors mentioned.

States’ perception of hybrid conflict

Comparative assessments of the selected states’ defense strategies between 2008/09 and 2018/19 reveal that hybrid conflict is increasingly recognized as a threat to the national security of these states.[3]

Recently, Russia has pointed out risks posed by external manipulation and subversion noting that “(t)he intensifying confrontation in the global information arena caused by some countries' aspiration to utilize informational and communication technologies to achieve their geopolitical objectives, including by manipulating public awareness and falsifying history, is exerting an increasing influence on the nature of the international situation”.[4] Russia also states that the use of economic coercion for geopolitical aims is destabilizing the international economic system.

Russia’s perspective on hybrid conflict is mirrored by other powers. China, for instance, makes reference to hybrid threats emanating from the US, namely through use of sanctions and political provocation.[5] In contrast to its 2008 equivalent, China’s 2019 defense white paper mentions hybrid threats, including the rise of cyber-related threats, the potential use of sanctions against companies and academics, and other states’ financial support of Tibet’s freedom movement.[6]

Recent defense strategies from Western states also increasingly recognize the destabilizing effects of hybrid campaigns. The US’ current perception of hybrid conflict focuses on cyber conflict, disinformation campaigns and economic coercion, explicitly designating China, Russia and Iran as dangerous protagonists.[7] Germany and the Netherlands are particularly anxious of cyber threats and information warfare. Germany moved from signaling a “digital lack of security” but without mentioning “hybrid” in 2008, to explicitly identifying hybrid conflicts as a rising and threatening trend in 2018.[8] The Dutch Integrated International Security Strategy (2018) frames hybrid conflict as threats such as foreign interference through disinformation, cyber espionage, sabotage and foreign funding.[9] Over a ten year period, the UK exhibits a heightened awareness of hybrid threats in the cyber and political domain, especially with regard to safeguarding electoral systems.[10]

Awareness and recognition of hybrid conflict represents the first step in countering and building resilience toward threats in this domain. Broad awareness of hybrid threats at the state and societal level challenges their subtle nature, thus limiting the ability of perpetrators to launch attacks undetected. Whilst this growing recognition is a positive trend, some experts note that as our understanding of security shifts from traditional to hybrid conflict, we may perceive our societies to be in a constant state of war.

States’ intention to use hybrid means

As awareness of hybrid conflict grows, many states are disclosing their intentions to use hybrid means defensively. States are making more explicit mention of their intent to actively protect themselves by using diverse means. This reflects how the phenomenon of hybrid conflict is perceived as a threat that must be addressed by a range of innovative means.

Having invested in hybrid strategies more overly in the past compared to other states, Russia remains committed to ensure strategic deterrence through the sustainment of a hybrid strategy that combines a range of different measures.[11] Likewise, China’s latest defense strategy reserves “the option of taking all necessary measures” to safeguard China’s national sovereignty, security and interests.[12] Overall, such intentions are expressed to a greater extent than ten years ago.[13]

The cyber domain represents an exception to the broad trend of states framing their intentions to use hybrid means in defensive terms, as states increasingly disclose their intentions to use offensive cyber measures against other states.[14] The UK, for instance, stresses their willingness to use armed force to defend itself from cyberattacks and to protect their networks, when needed by targeting the networks of the attacker.[15]

Capabilities

States are increasingly investing in government agencies that engage in or respond to hybrid conflict, enhancing their defensive and offensive capabilities. This is true for all states considered here (China, Russia, the US, France, Germany, the UK and the Netherlands), all of which have created, invested in and widened the scope of such government agencies over the past ten years.[16] Whilst the capabilities of these states have increased accordingly, it is important to note that many capabilities in this domain lie outside of the ’official’ governmental or even institutional sphere. In addition to employing public organizations and agencies, many states carry out hybrid operations through non-state actors or through covert units.[17]

Russia’s capabilities are illustrated by the increased presence of the Russian Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces (commonly referred as GRU) in the cyber domain, as well as the Russian Internet Research Agency, which is involved in “Bot-farms” and disinformation campaigns.[18] In China, the PLA Strategic Support Force (home to the Unit 61398, among others) has been mentioned by experts as a hybrid-focused force, with tasks including information warfare and cyber operations. China’s whole-of-government approach to conflict and security means that several government agencies not specifically designated as ‘hybrid’ actors may play a coordinated role in these activities.[19]

The US Cyber Command is another example of a military-focused agency with an important role in hybrid conflict, as exemplified by a cyberattack the Command undertook against Iran during July 2019.[20] The Netherlands is currently developing a Counter Hybrid Unit, implying an increase of spending on, and in future greater capabilities to counter hybrid conflict.

Although the NATO member states analyzed have been pushing to enhance capabilities to counter hybrid measures, these efforts appear to primarily focus on cyber capabilities.[21] Increasing funding and staffing of the National Cyber Security Agency of France (ANSSI), and the creation of a German Agency for Innovation in Cyber Security exemplify this observation.[22] Indeed, of the NATO states analyzed, only the Netherlands has a unit specifically dedicated to countering hybrid threats as a whole, in addition to cyber units. This juxtaposes the attitude of Russia and China who actively pursue a broad range of hybrid capabilities with a whole-of-government approach.

Whilst overall the government agencies engaging in or responding to hybrid conflict appear to place focus on defensive capabilities, states such as Russia and China have built capabilities within their agencies that are being utilized actively and offensively. In line with the rising perception of hybrid conflict as a threat to national security, states will continue to create, invest in and expand specialized agencies designed to effectively respond to this evolving threat environment.

Military activity

The use of proxies by state actors in third party military conflicts

As interstate competition heats up, states are increasingly engaging in proxy conflicts.[23] Proxy conflicts arise when states “instigate or play a major role in supporting and directing a part to a conflict,” but do only a small portion of the fighting themselves.[24] These conflicts allow states to secure ideological and/or strategic objectives without putting a significant number of their own troops at risk.[25] Proxy wars also offer the opportunity to test and showcase new weapons systems, facilitating a learning process which would otherwise only be available within the context of interstate conflicts.[26] Proxy wars can be understood as a form of hybrid conflict because states’ systematic denial of involvement in these conflicts lowers the likelihood of retaliation as the degree of responsibility for the groups that they control is obscured.[27] Moreover, there are well-documented instances of proxy-activities being employed to secure objectives which fall outside these conflicts’ direct geographical scope, rendering them hybrid in nature. As an example, Russia’s involvement in Syria has been linked to its wish to secure its naval base in Tartus and to its patron-client relationship with the Assad regime.[28]

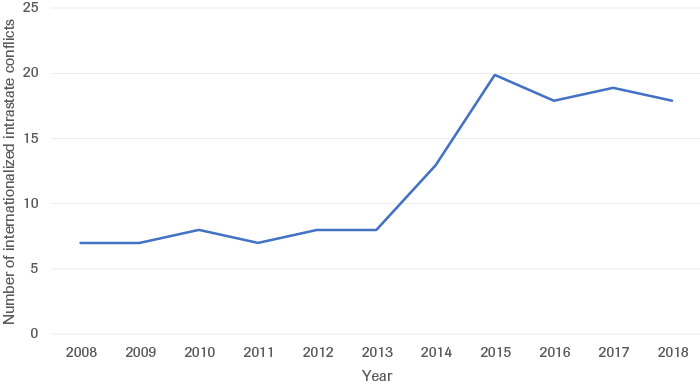

Within the context of this research, the volume of proxy wars is measured by means of the Uppsala Conflict Data Program’s internationalized intrastate conflict measurement. This approach was taken because no comprehensive vetted dataset committed to cataloguing proxy wars as a phenomenon exists.[29] Internationalized intrastate conflicts are defined as civil wars in which external military forces intervene and fight in support of at least one of the warring sides, and generally present states with the same opportunities as do proxy conflicts, meaning that state motivations for engaging in them are typically the same.[30] The number of internationalized intrastate conflicts more than doubled from 2008 to 2018, increasing from seven to eighteen. Crucially, between 2013 and 2014, the rate of conflict onsets doubled, rising from eight to twenty. The most recent figures from 2018 show that the number of internationalized intrastate conflicts has since regressed slightly to eighteen, thus accounting for 35% of all conflicts in 2018 (as opposed to 18% in 2008).[31]

Source: UCDP

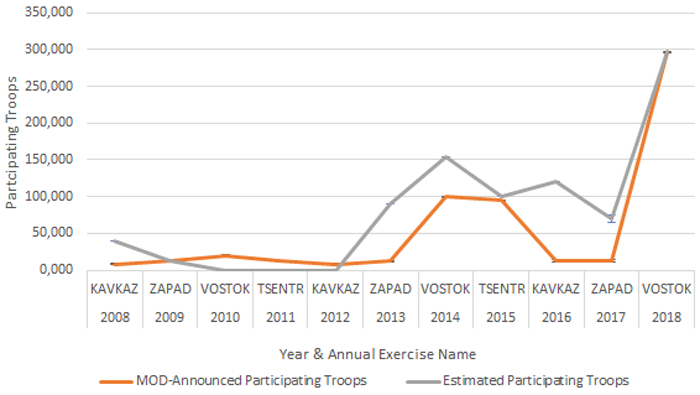

Cross-referencing these conflicts with data available through other sources shows that the number of actors involved in these proxy-conflicts has increased from an average of 3.7 actors per proxy-conflict in 2008 to 5.8 actors in 2018 (Figure 2). This data indicates, not only that proxy conflicts are becoming more complex overall, but also that states are engaging in them more actively as a means of waging hybrid conflict. Indeed, the persistence of proxy conflicts is highly predicated on the support of states that keep warring factions alive through financing, arms and logistical support.

Source: UCDP, Open Source; modified by HCSS

The upward trend in the use of proxy forces extends into cyberspace where states increasingly rely on cybercriminals as extensions of state power.[32] An example is the activities of the Mabna Institute, a non-state actor associated with Iran. This group recently hacked into the Australian Parliament’s computer system as part of their cyberespionage campaign to target members of FiveEyes.[33] The Chinese incentivized groups to hack Taiwan ahead of its elections, with the goal of undermining a leadership that has so far defied Beijing’s interests.[34] Moreover, there is evidence suggesting the hacker group Advanced Persistent Threat 41 (APT41) was tasked by China to gather intelligence on individuals involved in Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement.[35]

Military exercises near borders

Military exercises near the borders of (potential) adversaries is a well-established practice designed to intimidate without crossing the threshold into conventional conflict. The OSCE’s Vienna Document stipulates that states are required to notify each other forty-two days prior to major military activities near borders, including military exercises.[36] However, Russia (a signatory state to the Document), frequently bypasses this confidence and security building measure (CSBM).[37] With a lack of effective CSBMs in place, these military exercises have the potential to exacerbate instabilities and lead to escalatory retaliations.

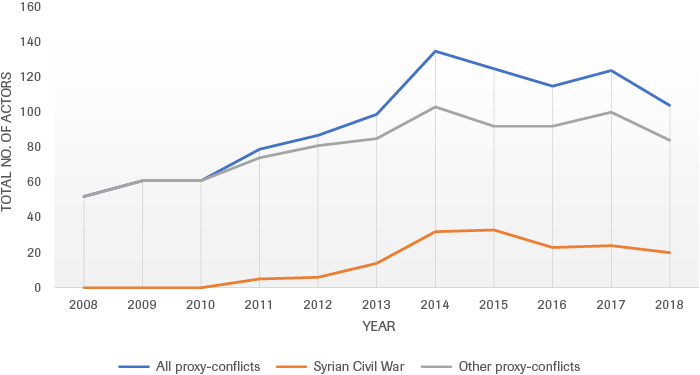

There has been an intensification of military exercises near borders over the last ten years, and especially over the last five years.[38] They have become both larger in scale and more regular in occurrence.[39] This overall trend has been rising since 2014, reflecting Russia’s military interference with Ukraine and resulting escalation. 2014 marks the beginning of an upturn in Russia military exercises near borders which perpetuates to the time of writing (Figure 3).[40]

Source: NATO review

In 2018, NATO staged its largest military exercise since the end of the Cold War. ‘Exercise Trident Juncture’ saw naval operations taking place along the Norwegian coastline, air operations over Sweden, and land and amphibious operations on Sweden’s eastern coastline.[41] This coincided with a Russian exercise in international waters off Norway’s Kristiansund. Recently, Russia sent a powerful message to the West by holding a military exercise with China, Pakistan, Kyrgyzstan, India, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan in September 2019.[42] In response, the US and Europe conducted ‘DEFENDER-Europe 2.0’, the largest exercise of its kind conducted in 25 years.[43]

In another disputed area of the globe, China frequently holds military exercises with other Indo-Pacific states to securitize the area. For instance, China held a military exercise with other ASEAN nations, crucially excluding the Philippines who have brought a case to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague in protest of China’s actions.[44] In response to the US Navy’s exercise in the area in October 2019, the Chinese held an exercise to solidify their presence over the South China Sea.[45]

Aerial and maritime intrusions

There is a growing trend in aerial and maritime activities that stay below the threshold of an actual confrontation. Intrusions are exercises that deliberately and provocatively (threaten to) enter other states’ territories. The contribution of Russia and China to this trend garner international attention and therefore these two states warrant close examination in this section. In terms of aerial intrusions, NATO considers Russia to be an increasingly provocative actor, particularly in the Baltic region.[46] In terms of maritime intrusions, the number of Chinese intrusions in foreign territorial seas reached record highs this year, particularly in the South China Sea.[47]

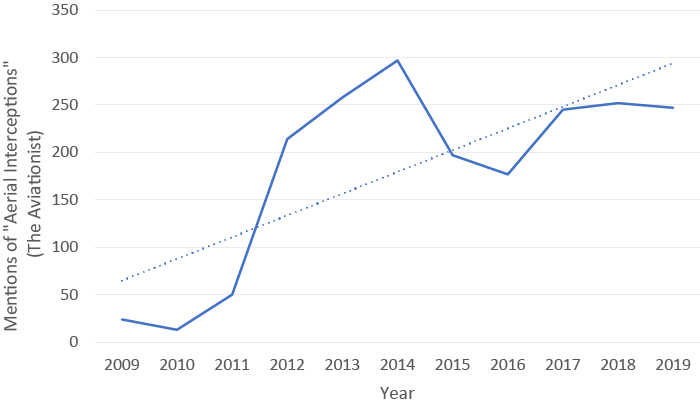

An assessment of “The Aviationist”, one of world’s most authoritative military aviation websites, has revealed a much higher volume of mentions referring to aerial intrusions over the past ten years, indicating an increase in such incidents.[48] Assessments reveal a slight incline in interceptions of Russia’s aerial activities over NATO territory, but also a more striking trend toward indirect interferences that provokingly threaten, but do not violate, NATO territory. In 2014, Russian aircrafts flew into Estonia’s airspace 130 times, a three-fold increase from the previous year, marking the starting point of Russian aerial activity around the Baltics.[49] In May 2019, the British Royal Air Force noted further increase to Russian air activities in the region.[50] This ties into a larger trend of Russia signaling its military readiness.[51] Whilst there is no record of actual aerial interceptions, Norway has reported mock strikes on its radar stations getting dangerously close to its airspace, as well as communications interference in the form of electronic jamming which are believed to be orchestrated by Russia.[52]

Source: The Aviationist

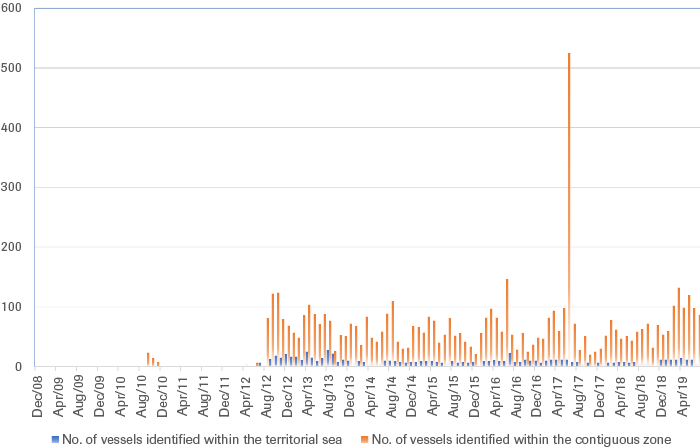

Similarly, expert analyses reveal that, since 2008, Chinese military naval activities have increased in the East and South China Sea.[53] According to the Japanese Foreign Ministry, the number of vessels within Japan’s territorial waters and the contiguous zone rose in 2012 and have since remained consistently high (Figure 5).[54] The number of vessels in the contiguous zone is approximately twice as high as those witnessed in territorial waters, speaking to the notion that most Chinese maritime activities have not directly violated littoral states’ territorial integrity, but have rather taken a more blurred approach, typical of the hybrid domain. In 2017, this number spiked considerably, which can be linked to a more aggressive approach taken by China in the first half of 2017 when it departed from sending only ships into the disputed territories and began to also use unmanned aircrafts.[55] Overall, the Chinese increasingly employ both military and paramilitary law-enforcement ships in order to patrol and curb the influence of other actors in the waters.[56] In combination with building military facilities and equipment on artificial islands in the South China Sea, this militarization has enhanced China’s position here considerably. Moreover, China continues to clash with the US in the South China Sea, involving increased military encounters that enhance the potential of serious incidents between the two powers.[57]

Source: Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Political activity

Stimulated by technological advancements and increasing international tensions, external political meddling during the last ten years has surged. Meddling activities include, but are not limited to, disinformation campaigns, cyberattacks and economic coercion. Technological advancements have allowed for cheaper influence campaigns, reducing the threshold to engage in these activities. This is particularly true within the information and cyber domains, as the development of bots and deepfakes enable influence over civil society with more reach, ease and impact than ever before.[58] While some examples are well known, such as the US 2016 Election interference, or the 2017 French election interference, political meddling as a hybrid tactic occurs on a global scale.[59]

Differences in the approaches of executing meddling campaigns appear to be due to distinctions between the institutional strength of target states.[60] Less resilient societies such as those in the Western Balkans, tend to fall pray of economic coercion and corruption.[61] In Western Europe, where institutions are more equipped to repel economic coercion and corruption, cyberattacks and disinformation campaigns are far more common, as the population’s dependence on technology is taken advantage of.[62]

In Europe, Russia is the most propagated and the most visible source actor. Its toolkit includes cyberattacks, disinformation, economic coercion and energy manipulation.[63] In addition, Russia is using proxy organizations, such as the Wagner Group, to manipulate elections and exercise pro-Kremlin influence in Africa. Meanwhile, China is mainly associated with applying pressure on high-level political circles and fostering economic dependencies which can later be exploited for political purposes through economic coercion.[64]

However, this type of meddling can hardly be considered exclusive for China and Russia, as the US have long been accused of this type of behavior.[65] A recent example of (alleged) political interference was that of Obama administration officials in Afghanistan elections of 2009.[66] Moreover, political meddling through personal relationships, corruption and disinformation has become an open reality in Latin America, as highlighted by the intervention of Argentina and Venezuela in 2018 Brazilian elections through bots.[67]

Economic activity

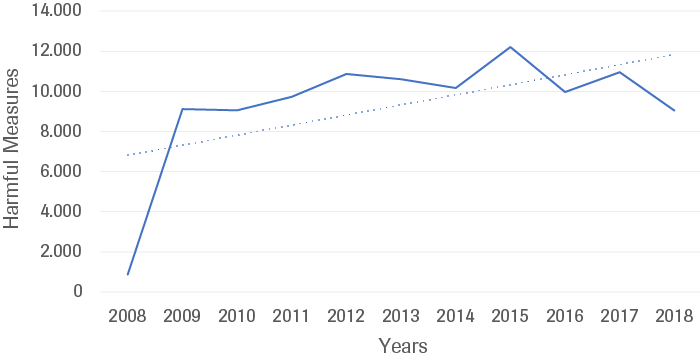

States are increasingly resorting to coercive economic measures to achieve their political interests.[68] Economic coercion is the employment of economic tools to exert targeted influence, and exploit vulnerabilities and interdependency relations for political purposes.[69] The rising level of ‘harmful measures’ to the global economy indicates that economic coercion has become more pervasive in the last ten years.

Source: Global Trade Alert; measures filtered by their relevance to economic coercion, filter designed by HCSS

Terms relating to economic coercion, such as sanctions, boycotts and embargos feature more centrally in the discourse over the ten-year period, further corroborating this trend (Figure 7). This can be traced to the increasing assertiveness of the US, where sanctions seem to be considered as a “go-to” option for conflict resolution. Recurrent threats from the US toward China and Chinese state-owned enterprises, Iran and Iranian officials, Russia, and Turkey, can be assumed to account for the dramatic spike seen in 2018. Indeed, to force the release of an American pastor accused of involvement in Turkey’s 2016 coup, President Trump publicly and successfully initiated sanctions and tariffs against Turkey.[70] Further recent instances of the US engaging in economic coercion include the continued utilization of EU-based companies (such as SWIFT) to deny Iran access to the international financial system.[71] Alliances aside, the US is also considered as a threatening economic actor for the EU, due to the direct and indirect consequences economic coercion has on the EU economy.[72]

Source: ICEWS

Recent examples of China’s activities in Sri Lanka and Djibouti exemplify the impact of economic coercion on the military domain.[73] The Sri Lanka-China case shows “debt-trap” dynamics, whereby Sri Lanka, unable to repay loans to China, has been compelled to lease the Hambantota port to China.[74] In the case of Djibouti, a rising economic dependency on China is laying the ground for non-economic infrastructure projects, such as a naval base built in early 2017.[75] Following this example, other states may adopt similar strategies, which is arguably occurring in the Western Balkans under Turkish economic coercion.[76]

We observe a tendency of states becoming more aware of the use of the more subtle forms of economic coercion as a political tool. This can be seen through the EU’s interest in regulating its relationship with China, with e.g. a further screening of investments.[77]

Information activity

The use of disinformation campaigns to influence societal discourse is on the rise. A disinformation campaign is the targeted spread of false information that is designed to deceive and influence.[78] For the purposes of this report, the term disinformation is separated from the related terms of “information warfare” and “psychological warfare” (which pertain to armed conflicts), in order to focus the discussion on the purposeful influencing of the public with the intent to cause societal disarray, polarization and impact democratic processes. While propaganda and the malicious spreading of false information are by no means a new phenomenon, modern disinformation campaigns are distinct due to their reach, frequency and subsequently, their impact. Recent campaigns are strengthened by technological innovation in the dissemination of false information (for example, through bots on social media), as well as in the mediums of false information (for example, deepfakes). The unrelenting evolution of disinformation strategies means that Western states seem to continually be a step behind in their counter actions.[79]

Disinformation campaigns vary by source state, methodology and motivation. The analysis reveals a predominance of examples emanating from Russia. This is reflective of the constant presence of Russian disinformation strategies as well as the expanding geographical scope of Russian disinformation campaigns over the last ten years.[80] Two recent manifestations have been the disinformation campaigns launched ahead of the Presidential election in France and the independence referendum in Catalunya, both in 2017. The former shows how foreign adversaries can propagate false information through bots and spread disruptive information obtained through cyber espionage.[81] The latter is an example of the use of bots and disinformation to exacerbate discontent and aggravate existing social tensions.[82] Further examples of Russian disinformation campaigns ‘going global’ can be observed through the role being played by RT and Sputnik in the ongoing Chilean and Bolivian crises.

Whilst our understanding of modern disinformation may be dominantly shaped by Russian activities, an increasing amount of states are also active in this domain. India, Iran, North Korea and Saudi Arabia are all developing capabilities in information manipulation.[83] In accordance with their ‘Three Warfares’ principle, China is becoming a more active and important actor in information warfare.[84]

In the near future, two trends, namely the role of social media in the dissemination of false material, and the role of technologies, such as “Generative Adversarial Networks” that allow for the creation of highly sophisticated audio-visual manipulations (deepfakes), will shape the information domain.[85] These technological shifts in the dissemination and production disinformation mean that counter initiatives—whilst showing signs of success—are aiming toward a fast-moving target.

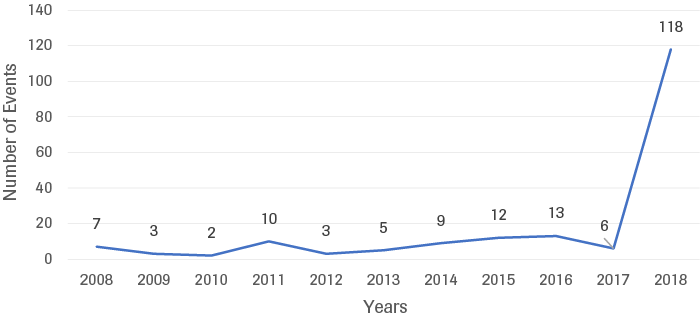

Civil activity

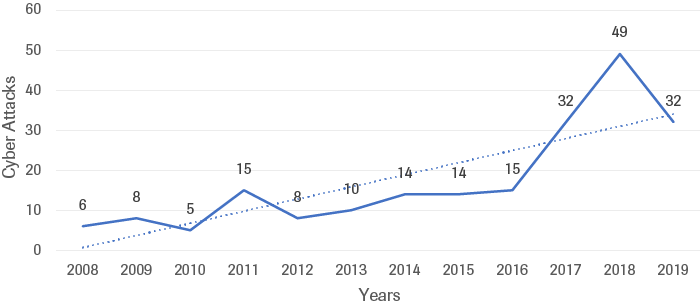

The number of cyberattacks on states’ critical infrastructure has risen steeply over the last decade (Figure 8). A cyberattack on critical infrastructure is the exposure or destruction of, or gaining of unauthorized access to, systems that provide food, water, energy, transport, communications or healthcare.[86] Examples of such attacks include the 2012 cyberattack on a Saudi national oil company Saudi Aramco and two attacks perpetrated in 2015: the ‘WannaCry’ ransomware attack on the UK´s National Health Service, and the attack on Ukraine´s energy distribution company. In 2018, the US Government warned that actors associated with the Kremlin were conducting cyber reconnaissance on energy, nuclear, water and other critical infrastructure sectors in the US, possibly in preparation for targeted attacks. Critical infrastructure attacks are designed to cripple vital services, potentially leading to civil chaos, disaster and loss of life. Difficulties in establishing responsibility and retaliating against cyberattacks of this kind make this tactic an attractive means to weaken a target via their most critical services.

Source: CSIS & CFR

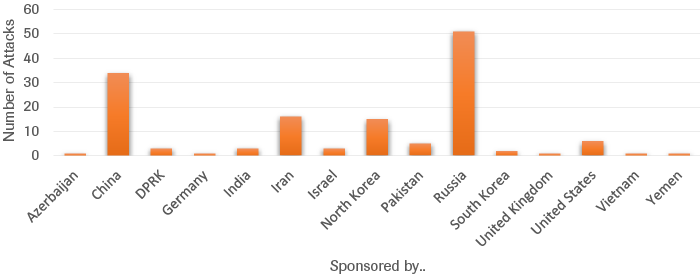

An assessment of the most significant cyber incidents reveals that most attacks on critical infrastructure were state-on-state in nature and were executed through cyber espionage.[87] According to this data, the most frequent actors to target other states’ critical infrastructure were Russia, China and Iran, closely followed by North Korea (Figure 9). The main targets of such cyberattacks have been the US, South Korea, India and Ukraine.[88] Many of the events do not correspond to a military conflict, showing that this tool is increasingly being employed to operate in the grey zone next to indirect support of military operations (such as the 2008 Russian-Georgian war or the Ukrainian-Russian conflict).[89]

Source: CSIS & CFR

Sub-conclusion: A Rising Tide

Over the past ten years, hybrid threats have proliferated within the international security environment and altered our understanding of conflict. Though states are becoming more aware of the facets of this subtle and multidimensional style of conflict, increased awareness does not always instigate the development of concrete capabilities. A significant capability gap exists between the advanced whole-of-government approaches of Russia and China, and some slower-acting Western countries.

In the military domain, the increased prevalence of hybrid conflict is substantiated by rising trends in the use of proxy actors, the execution of military exercises near borders, and intrusions into airspace and territorial waters. The act of external meddling in the domestic politics of foreign states has become more common and widespread as technological developments enhance the ease and impact of this form of interference. Furthermore, trade and event-related data shows that economically coercive tactics are increasingly influencing the international environment. In addition to these military, political and economic strategies, this rising level of hybrid conflict permeates to the information and cyber domains, where the dissemination of false information as well as cyberattacks on critical infrastructure has become part-and-parcel of the current competition between states.

It appears we are facing conditions favorable to the existence and continuation of hybrid conflict. First, the availability of diverse, relatively inexpensive and easily accessible, sophisticated (technological) tools that can be utilized to achieve strategic goals is enhancing the impact, reach, and congruence of hybrid strategies. Second, states are currently able to take advantage of an international order that is not yet fully equipped to respond to the challenge hybrid conflict poses (and is being simultaneously threatened by other phenomena). Combined with states’ unprecedented aversion to engage in conventional warfare, this means that hybrid conflict is a highly desirable strategy to achieve political goals and will remain so in the foreseeable future.

International Order

Introduction: Neither war, nor peace

By nature, hybrid strategies seek to evade the thresholds and constructs set out by international law, thus posing a significant challenge to the international order. This section will explore how hybrid conflict interacts with, and exacerbates the flaws of, the international order.

The concepts that shape the current international order are not completely compatible with today’s reality of hybrid conflict. The shift from the interstate armed conflicts to hybrid conflict means that traditional legal rules (or at least the interpretation and application thereof) may be out of sync with reality. This disparity does not only cause dissonance in the processes of determining whether there is indeed a conflict at all, but also in the processes of undertaking collective (counter) action, resolving disputes and seeking appropriate (legal) remedies. As such, hybrid conflict – despite not being an entirely new phenomenon – has seriously impacted, and holds the potential to further affect, the conceptualization of conflicts as well as the development of legal norms.

The post 1945 paradigms of the right to wage war (jus ad bellum) and the abundance of codified and non-codified norms on the conduct of parties engaging in armed conflict (jus in bello), are not always directly applicable and do not yield the necessary remedies to hybrid conflict. Taking the above into consideration, it is crucial to remind ourselves of the importance of law vis á vis hybrid conflict. Law is an instrument of power and can be utilized as a weapon by law abiding and non-law-abiding actors alike.

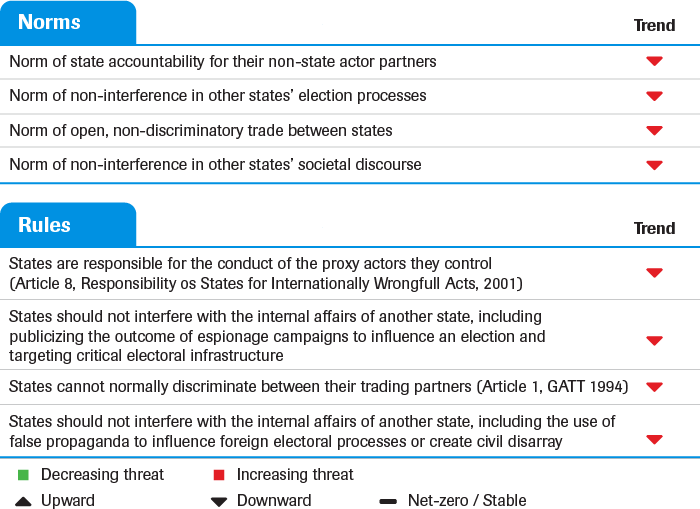

States that engage in hybrid conflict use law as a tool to systemically exploit existing fault lines and gaps in the international legal order for strategic ends.[90] In this section we explore four norms that explore the ways in which hybrid activities in the international arena are insufficiently checked by international law (in its current interpretation and application) (Table 2). The first norm shows that states engaging in military conflict through proxy actors actively evade attribution under law. The subsequent three norms, which pertain to the political, economic and information domains respectively, highlight that non-kinetic hybrid tactics, such as political meddling, economic coercion and disinformation campaigns, are not comprehensively accounted for in international law. As hybrid conflict continues to blur lines between war and peace (on which international regulatory frameworks depend), our understanding of what actions are unacceptable becomes vague. This perversion creates dysfunctional responses and confusion among decision-makers and ordinary taxpayers alike.

Norm of state accountability for their non-state actor partners

States increasingly use proxy actors to indirectly influence conflicts. This evolving trend has important implications for international norms on the use of force and state accountability for their non-state actor partners. There is a wide realm of situations in which state and non-state actors can, jointly or separately, bear responsibility for the commission of, or contribution to harmful outcomes, abuses and/or violations of (international) legal norms. The International Law Commission Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts (2001) (hereinafter the ILC Articles), provides a legal framework for understanding state culpability for the actions of their dependent proxy organizations. Proxy actors lack the international legal personality necessary for accountability and are not legitimate players in the international arena.[91] It is, however, important to note that the ILC Articles stem from customary international law. It took nearly 45 years and more than thirty reports by the International Law Commission to come to an agreement despite the general (and arguably vague) nature of the ILC Articles.[92]

As per the legal nature of UN GA Resolutions, the ILC Articles are not legally binding.[93] According to Article 10 of the United Nations Charter, the United Nations General Assembly makes recommendations on matters within the nature of the UN and the scope of the UN Charter. This said, these recommendations contribute to the progressive development and codification of international law and some level of global custom may also be reflected through the voting patterns of the members of the United Nations within the General Assembly.

Article 8 of the ILC Articles states that “The conduct of a person or group of persons shall be considered an act of a State under international law if the person or group of persons is in fact acting on the instructions of, or under the direction or control of, that State in carrying out the conduct.”[94] From this rule follows the wider norm of state accountability for the wrongful actions of the proxies they control. This logic is linked to the traditional notion of states holding a monopoly on the legitimate use of force and thus, being accountable for their military actions (e.g. when violating international humanitarian law).[95]

The high threshold for establishing states’ ‘strict control’, ‘effective control’, or ‘overall control’ over proxy actors means that state responsibility has rarely been established.[96] The rarity of the international legal system holding states accountable for their non-state subordinates speaks to the erosion of this norm in practice. In cyberspace, the complexity of attributing attacks to perpetrators offers a further promise of anonymity to states that support or coordinate the attacks of non-state actors.[97]

Certainly, states will continue to operate through proxies and reap the political and legal advantages of detachment from culpability. However, though this trend has consequences for deterrence, a shift toward the normalization of proxy conflicts does not imply state impunity. Rather, offending states are subject to the target states’ right to self-defense, and thus proxy actors may trigger military and diplomatic repercussions outside the realm of international legal responsibility.[98] The inability of international law to effectively account for non-state actors thus leads to a situation whereby states must address and solve conflict though alternate, sometimes escalatory means. This dynamic leads to further instability in the international order.

As states continue to embrace hybridity and ambiguity in conflict as opposed to traditional warfare, the norm of state accountability is being eroded. The increasing activity of proxy actors in various conflicts demonstrates that Article 8 of the ILC Articles (and the norm of state responsibility that it reflects) is being continually violated by some states.

Norm of non-interference in other states’ election processes

External interference in states’ critical infrastructure and societal processes – such as elections - is growing. The cyber domain is of crucial importance here as it facilitates the acquisition of information via espionage campaigns, the targeting and/or disruption of critical infrastructure and as the dissemination of disinformation. To date, there is no commonly accepted or codified norms on the non-interference in other states’ election processes, neither in general nor in relation to cyber means.[99] However, vital principles of international law are more often applied to this question and a set of initiatives are indicative of norm development on the matter.

Next to the principles of state sovereignty and self-determination, the principle of non-intervention is one of the core purposes and principles contained in the Charter of the United Nations, under Art. 2(4) and Art. 2(7) of the present Charter. The premise of the principle is simple: sovereign states shall not interfere in each other’s internal affairs. It applies to matters of sovereignty, territorial integrity, internal governance and conduct of foreign affairs. Though not explicitly referring to elections, this principle is gradually extending to the protection of critical electoral infrastructure, given that this area forms part of states’ sovereignty, its political system, independence and stability – elements which are all covered under the principle of non-intervention.[100] From this logic follows the rule that states should not interfere with the internal affairs of another state, including publicizing the outcome of espionage campaigns to influence an election and targeting critical electoral infrastructure. It should be noted that the practice of states committing espionage for political purposes is a normal and well-established tool in international affairs. However, using the intelligence gathered to undermine and interfere with a foreign election is in violation of the spirit of the norm of non-intervention.

The development of a normative and regulatory framework to protect states’ sovereignty, its political system, independence and stability against foreign interference has been initiated. As an example, in October 2019 the European Parliament adopted a resolution on foreign electoral interference and disinformation in national and European democratic processes.[101] The resolution stresses that foreign electoral interference constitutes a major challenge to European democratic societies and institutions, and directly links this type of interference to “a broader strategy of hybrid warfare”.[102] In light of this interference, states and international organizations are increasingly framing electoral processes and electoral infrastructure as part of the critical infrastructure of a state.[103] The designation of electoral processes as critical infrastructure will enable responses to breaches of these processes to mirror those currently in place for breaches of the energy and transport sectors.

However, this (evolving) normative framework is already being eroded before it is even consolidated as part of customary international law.[104] Even though the principle of non-intervention is binding for all states, in the context of election processes the principle is being violated frequently. The most prominent example of this has been Russia’s interference campaigns in the 2016 US presidential elections via the hacking of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and subsequent leaking of sensitive documents.[105] In Ukraine in 2014, pro-Russian groups released hacked e-mails, tried altering vote tallies and delayed the presidential elections’ result.[106] While some protection measures can be implemented against this interference, it is unclear how states can respond to and retaliate against perpetrating states under international law, further complicating the implications of this growing trend to the international order.

External meddling in states’ elections shows that the principle of non-interference is under mounting pressure. The norm of non-interference as it pertains to election processes is a norm that was previously taken for granted by states. The rule of non-intervention in the internal affairs of other states has recently been infringed upon to the degree that the rule can said to be broken, signifying that the norm is under significant threat. The increasingly overt violation of this norm poses a significant challenge to the electoral systems of states and infringes upon the very basic rule of the international order: sovereignty.

Norm of open, non-discriminatory trade between states

States are increasingly employing economically coercive measures to achieve their strategic goals through targeted influence, and the exploitation of vulnerabilities and interdependency relations.[107] The US-China trade war is the most prolific and recent example of this. This coercion occurs despite a well-developed international trade regime that prohibits the use of discriminatory trade practices under normal circumstances.

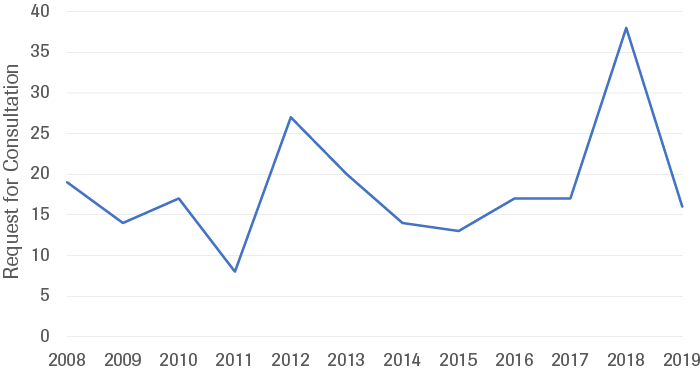

Of crucial importance to the international trade system is the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the less institutionalized precursor of the WTO, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). The core purpose of the GATT is to contribute to the “substantial reduction of tariffs and other trade barriers and the elimination of preferences on a reciprocal and mutually advantageous basis”. The crowning achievement of the WTO is the dispute settlement mechanism. WTO members must use the dispute settlement mechanism for their complaints and states may not act unilaterally in response to actions they perceive to be a violation of WTO rules, as this risks instigating a spiral of protectionism.[108] Data on WTO disputes is merely indicative of the violation of WTO rules, it cannot be used to directly exemplify adherence (or non-adherence) to the global trade regime as many states refrain from bringing disputes to the WTO. Developing economies in particular (indeed, those that are most vulnerable to economic coercion) experience barriers to the settlement procedure such as a lack of expertise and financial capacity to enter into a lengthy and demanding disputes process. Additionally, as disputes typically take years to conclude, the economic harm felt by a state may be too difficult to endure for the entirety of the case and states may thus seek alternate means to address their complaints, though unilateral retaliation is in violation of WTO rules.[109] This said, the increase in requests for WTO dispute consultation is partially indicative of the implementation of tariffs as a political measure and reflects the increasing violation of the norm (Figure 10). The number of requests for consultations spiked in 2018, following the Trump administration’s levying tariffs throughout 2017. The violation of the principle of non-discrimination, perpetrated by the world’s two largest economies US and China, signifies a departure from the rules-based international trade system.

Source: WTO

The international trade system has experienced significant challenges over the past ten years and the norm of open, non-discriminatory trade has been negatively affected by the employment of economically coercive measures by states. This norm is intrinsically encoded into the rules established and maintained by the WTO, and therefore the violation of the rule of non-discrimination threatens the norm as whole. When states break (or threaten to break) the rules of the WTO, it undermines the notion that free trade is a given. The strain on the norm is further heightened by the overt nature of the US-China trade war. Recent actions by the US that effectively render the dispute settlement body of the WTO paralyzed signals contempt towards the value system of international trade. In sum, the rules of the WTO and the corresponding norm of open, non-discriminatory trade between states is under increasing pressure.

Norm of non-interference in other states’ societal discourse

Disinformation campaigns are a form of societal interference that seek to influence public opinion with false information. Similarly to the previously discussed ‘norm of non-interference in other states’ election processes’, the principle of non-intervention is the most appropriate lens to analyze how the growing trend of interference with foreign states’ societal discourse is challenging international norms.[110] The findings of the International Court of Justice in the Nicaragua Case of 1986 highlights how the principle of non-intervention extends from the political domain (discussed earlier in reference to political meddling) to the economic and civil domains. In this case, the Court re-affirmed that the principle forbids all States or groups of States to intervene directly or indirectly in the internal or external affairs of other States and that "a prohibited intervention must accordingly be one bearing on matters in which each State is permitted, by the principle of State sovereignty, to decide freely. One of these is the choice of a political, economic, social and cultural system…"[111] This ruling constitutes a common law rule on the matter of interference in the societal discourse of foreign states.

Disinformation campaigns create societal disarray by polarizing public discourse, deepening tensions in society, and misinforming the public on key facts pertaining to healthcare, the environment and security. A well-known subsequent effect of disinformation is the undermining of political processes. Recently, the international community has sought to actively discuss and respond to the enhanced scope, frequency and impact of disinformation that is enabled by cyber means. The Tallinn Manual stipulates that cyber operations that fall below the use of force threshold, but are executed with the intent of a regime change, constitute a prohibited intervention.[112] The Manual specifically references the following examples as cases in point: the cyber-enabled manipulation of public opinion with relation to elections, the alteration of online news services to the benefit of a particular political party, the spread of false news, and the sabotage of a political parties’ online services.

Control over the narrative is a formidable source of power for a state to draw on. Democratic regimes rely on constituents as a source of stability and thus, creating chaos in societal discourse through disinformation provides an inexpensive and effective means to undermine adversaries. The continued use of disinformation campaigns by some state actors for this purpose show a blatant disregard of the norm of non-interference as it pertains to the societal domain. Whilst the norm overall is still present, disinformation campaigns continue to expand their reach, frequency and level of sophistication, permeating foreign societal discourse. Despite the notion that targeted disinformation campaigns run counter to the spirit of the principle of non-interference, the pervasive influencing of foreign public discourse and election outcomes is set to continue and further evolve.

Sub-conclusion:

Over the past ten years, hybrid conflict has seriously impacted the international order and the norms and rules that encompass it. States are able to evade responsibility for the actions of their proxies, thus eroding the norm of state responsibility for wrongful actions. External meddling in states’ elections shows that the principle of non-interference is under mounting pressure, threatening electoral systems and challenging the basic ordering principle of sovereignty. The international trade system, based on the norms and rules that secure open, non-discriminatory trade, has been negatively affected by the employment of economically coercive measures by states. Furthermore, the continued use of disinformation campaigns by some state actors for the purposes of causing societal disarray or influencing democratic processes demonstrates a blatant disregard of the norm of non-interference as it pertains to the societal domain. A common threat permeates these challenges to the international order: cases of hybrid conflict fall short of the high threshold of force required for the direct applicability of international law. This is no mistake-hybrid tactics are designed to evade repercussions.

The disparity between (i) the threshold of transgression in international law and (ii) the hybrid forms of conflict that we are currently experiencing, causes difficulties in defining thresholds of conflict and war, and hinders the formulation of appropriate counter measures for decisionmakers. Despite the disparity however, existing international legal norms can be further adapted, interpreted and applied to cases of hybrid conflict. Though they are under pressure, the norms discussed in this section (state responsibility, non-intervention and non-discrimination) have strong foundations and most actors in the international arena have keen interest in the integrity of these norms in the face of challenges posed by hybrid conflict.

Conclusion

The analysis in this report paints a rather bleak view of the international security environment vis á vis hybrid conflict. Over the past ten years, hybrid tactics have thrived within the international security environment, and include the use of proxy actors in third party military conflicts, the deployment of military exercises near borders, the intrusion of aerial and maritime territory, the exertion of influence over foreign democratic processes, the use of economic coercion, the proliferation of disinformation campaigns and the execution of cyberattacks on critical infrastructure. Despite not being an entirely new means of mobilizing against adversaries, these methods of hybrid conflict have seriously impacted the international order. Subtle tactics that are executed under the threshold of force place pressure on the international order regulating peaceful relations between states. By blurring lines between war and peace, our understanding of how to respond to hybrid conflict, both through measures at the state level and though international legal means, is lacking.

Notes

Sources for Russia: Dmitry Medvedev, ‘Russia’s National Security Strategy to 2020’, Pub. L. No. 357, Decree of the President of the Russian Federation (2009), link; Vladimir Putin, ‘The Russian Federation’s National Security Strategy, Presidential Edict 683’ (Russian Federation, December 2015), link;

Sources for the US; The White House, ‘National Security Strategy 2010’ (NSS Archive, 27 May 2010), link; The White House, ‘A New National Security Strategy for a New Era’ (The White House, 18 December 2017), link;

Sources used for France; Nicolas Sarkozy, The French White Paper on Defence and National Security, trans. ALTO, First (New York, United States of America: Odile Jacob, 2008), link; Republic of France, Defence and National Security: Strategic Review 2017 (Paris, France: La Délégation à l’information et à la communication de la défense, 2017), link;

Sources for the Netherlands; Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, ‘National Security: Strategy and Work Programme 2007-2008’ (The Kingdom of the Netherlands, May 2007), link; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ‘National Security Strategy 2018’;

Sources for the UK; Cabinet Office, Security for the Next Generation : The National Security Strategy of United Kingdom - Update 2009 (London, United Kindgom: The Stationery Office, 2009), link; Cabinet Office, National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015: Third Annual Report (London, United Kindgom: Cabinet Office, 2019), link; Cyber Securit Strategy of the United Kingdom: Safety, Security and Resilience in Cyber Space (London, United Kindgom: The Stationery Office, 2009), link; ‘National Cyber Security Strategy 2016 to 2021’, Strategy (London, United Kindgom: Cabinet Office, 1 November 2016), link.