Despite an increasingly hostile international environment and the need to work more closely together, EU cooperation continuous to be hampered by tensions between the national and European levels of government. These vertical tensions are visible in key policy dossiers as well as in principles of decision-making and democracy and the rule of law that underpin EU decision-making. This paper assesses to what extent the EU is coming together or falling apart; in both key policy dossiers and overall as an organization.

1. Introduction

The internal cohesion of the European Union (EU) is being tested by both internal and external challenges. These include mass migration, rising populism, a lack of respect for the rule of law, terrorism, and economic and monetary difficulties. These challenges have placed a huge strain on the bonds between EU Member States and illuminate the fragility of European unity and solidarity. Member States are increasingly unwilling to share sovereignty and comply with existing agreements, key norms and rules, and the rule of law. The result is an increase in vertical tensions between national and European levels of government — i.e., between the collective European interests — represented by the European Parliament (EP) and the European Commission (EC), and the national interests of individual EU Member States.[1]

Some take these vertical tensions as a sign that the EU is falling apart.[2] Others, like EC President Jean-Claude Juncker, claim that that EU Member States are actually working more closely together towards a common goal, in particular due to the current geopolitical situation.[3] The latter rationale is driven by the erosion of the transatlantic Alliance, increasing aggression from belligerent powers such as China and Russia, and the chaos surrounding the Brexit process.

To which extent is the EU coming together or falling apart when it comes to key policy dossiers? Does the EU, as a regime, have the capacity to manage or channel increasing tensions with and between its Member States?

This paper defines regimes as “a set of implicit and explicit principles, norms and rules and decision-making procedures around which the actors converge in a particular area of international relations.”[4]

Within regimes, norms are defined as standards of appropriate behavior. In the EU regime, norms are found in primary and secondary EU legislation and provide direction to the Union’s dealings in complex subject matters such as those central to this paper.[5] These include solidarity, consensus, shared sovereignty, compliance, and values of democracy and the rule of law. Rules are defined as concrete actions in policy dossiers as well as the general rules of EU decision-making.

In this paper we examine these claims by looking at six norms and rules that represent critical components of EU cooperation. These rules are identified in the 2018 EU State of the Union:[6]

Economic and Monetary Union (Banking Union);

Migration;

The Schengen Zone;

Defense cooperation;

Sound public finances;

Tax harmonization;

Principles of decision-making;

Democracy and rule of law.

This paper first analyzes the current state of affairs in the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), migration, defense cooperation and the Schengen Zone. The analyses of these topics include the definition of the regime at hand, the vertical tensions that pertain to it, and a key take-away. The paper will then look at two extra dimensions along which we measure how vertical tensions are influencing EU cooperation: 1) the principles of decision-making, and 2) democracy and the rule of law. The conclusion will provide an overall assessment of where and how the EU is coming together or falling apart and to what extent the EU regime has the capacity to manage or channel vertical tensions.

2. EU Cooperation in Key Policy Areas

2.1 Banking Union

Vertical tension: Despite progress on the Banking Union, economic and political divisions between the northern and southern Eurozone countries cause tensions, fueling mutual mistrust and raising questions such as ‘who pays for what?’ This hinders the completion of the essential third pillar of the Banking Union, the European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS).

The North–South split in the Eurozone can be characterized in many ways, some more accurate than others: debtor–creditor, deficit–surplus, grain–grape, and even Germanic–Latinate.[7] In general, the split is between the Eurozone’s North (including Austria, Finland, Germany, and the Netherlands) and the South (France, Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain). The first group are risk reducers who see institutional and market discipline as critical for a shared Banking Union. “They want to make sure the ‘bail in’ rules for banks, already in EU law, will be followed in practice. And they want banks to be forced to hold capital against their sovereign bond holding, adding to their equity buffers and thus making sovereign debt write-downs possible.”[8]

The South, the risk sharers, think the solution is to give the EU more power to intervene when things go wrong. They campaign for a common Eurozone budget and envision a Eurobond that would make banks and nations less vulnerable to bank runs and investor flights to safety. These more ambitious plans, the North has emphasized, should be left for future integration planning. Instead, they argue, Eurozone reforms should, first and foremost, focus on completing the Banking Union.

In 2012, and as a response to the crisis in the Eurozone, several Member States initiated the creation of a Banking Union.[9] The Banking Union was one of several financial integration measures implemented. These further included the intergovernmental rescue fund and the strengthening of economic governance in the EMU.[10] Since then, the first two pillars of the Banking Union — the single supervisory mechanism (SSM) and the single resolution mechanism (SRM) — have been fully implemented and are now operational.[11] However, the European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS), or a fiscal capacity to absorb sudden shocks hitting European economies, has not yet been implemented.[12] The reason for this is that Member States have concerns that the EDIS could create unfair risks and transfers of costs across countries. Northern Member States’ concerns lie in the high levels of non-performing loans.[13] Further monetary integration can thus be traced back to one key question: who pays for what?[14] This means that there is resistance among the North to act as guarantors for undercapitalized banks in the South. Implementing the EDIS would, however, eliminate potential impediments to financial integration, and could thereby help underpin a truly integrated banking system in the euro area.[15] On 4 December 2018, EU finance ministers sent the proposal on the EDIS back to the negotiating table.[16] Germany, the Netherlands, and a number of other countries have made it clear that they are not prepared for this form of European risk-sharing — which involves a lot of money — as long as no further progress has been made in the risk reduction at banks in, again, southern Member States.[17]

2.2 Migration

Vertical tension: Dividing lines between frontier states in the South and Central and Eastern European Countries (CEES) keep the EU from formulating a common approach to migration policy. Norms such as solidarity are side-lined by CEES countries when arguing that countries such as Italy and Greece are ‘on their own’ in this area.

During the European Council meeting on June 28, 2018, EU leaders reached a preliminary agreement on the politically controversial issue of migration policy. The conclusions of this meeting read that a comprehensive approach to migration will combine more effective control of the EU’s external borders, increased external action, and internal aspects in line with the EU’s norms of solidarity and finding a common approach.[18] In the same vein, the agreement mentions that as a result of effective EU external border controls, the number of detected illegal border crossings into the EU has decreased by 95 percent from its peak in October of 2015.[19] It also recognizes that the migration issue is far from solved, as migration flows have been on the rise from the eastern and western Mediterranean routes. The Council also noted that the threats of unchecked and uncontrolled migration between Member States jeopardizes the integrity of the Common European Asylum System and the Schengen acquis.[20]

The European Council has so far failed to reach a consensus in line with the EU’s norms of solidarity and shared responsibility, however.[21] This means that an agreement on reforming the Dublin Regulation on asylum policies has not yet been reached. Instead, led by efforts on the parts of France and Spain, consensus was reached on establishing ‘controlled centers’ in EU Member States on a voluntary basis and “without prejudice to the Dublin reform.”[22] This consensus does not solve Rome’s longstanding complaint that frontier nations like Italy and Greece are unfairly burdened by asylum seekers’ arrivals, and do not get sufficient help from other EU nations.[23] This will lead Italy and other southern states to renew their push for mandatory relocations of refugees under a quota system — an approach that has little support across the bloc. Other Member States are hawkish on the migration issue, such as Austria and the Visegrad Group (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia). These states remained adamant that frontier Member States should be responsible for enforcing border controls and pushed to limit the use of the word “solidarity” in the text of the compromise deal.[24]

The European Council conclusions call for “a speedy solution” on the reform of a new Common European Asylum System as well as a rewriting of the Dublin Regulation and the Asylum Procedures proposal. Faced with continuing opposition of the Visegrad Group, however, the Juncker Commission announced on 4 December 2018 that it has given up on Dublin asylum reform. Instead, the Commissioner for Migration, Home Affairs and Citizenship, Dimitris Avramopoulos, told the Brussels press that the time had come to be “pragmatic,” and called on the EP to adopt five out of seven agreements on the EU asylum reform where there is agreement. The five non-controversial proposals are the Qualification Regulation, the Reception Conditions Directive, the European Asylum Agency Regulation, the Eurodac Regulation, and the Union Resettlement Framework Regulation.[25]

2.3 Schengen

Vertical tension: Directly linked with the need for more effective control of the EU’s external borders and uncontrolled migration, temporary border controls have become more or less permanent in six European countries. This despite the fact that both migrant flows and the number of secondary movements have drastically decreased. Extending border controls undermines the EU’s free movement of goods and persons, and further tends to be guided by a political rather than a policy rationale.[26]

Following the uncontrolled migration flows of 2015 and illegal migration along existing and emerging routes, the principal underpinnings of the Schengen agreement have been openly called into question by EU Member States. Denmark, Hungary, and Austria, for example, reintroduced temporary internal EU border checks, restricting passport-free travel through the Schengen area. But since the refugee crisis of 2015, “temporary” border controls have become more or less permanent in France, Germany, Austria, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. Existing checks are now likely to be extended for another six months, after coordinated announcements this month from these six European countries.[27]

French authorities cite terrorism as a reason for this development, others name insufficient control of the EU’s external borders — despite plans to give extra funding to Frontex, the EU’s external border force — and shortcomings in the Common European Asylum System.[28] Migrant flows on all routes have decreased by 95 percent since the crisis, however, and the number of secondary movements has similarly decreased.[29] However, according to Germany and Austria the figures still remain too high.

These actions by European countries are restricting the four freedoms of the single market as set out in the EU Treaty.[30] Citing costs to commuters and the transport of goods by road, and depending on region, sector, and alternative trade channels, the EP estimates that the costs of rolling back Schengen would be between €5 billion and €18 billion per year.[31] In the context of these developments, a spokesman for the Slovenian government speaks of an “abuse of a system which is one of the cornerstones of the EU.”[32] The decision to extend controls despite declining arrivals shows that leaders are guided by “a political rather than a policy rationale.”[33] For example, and due to increasing nationalism and populism, the leaders of for example France, Germany, and Austria are under pressure to look and act tough.

Key take-away: The more or less permanent reintroduction of border checks by several European countries is undermining the EU’s four freedoms of the single market. In the light of current figures regarding migration and terrorism, there are no objective justifications for (continued) internal border controls. Rather than a policy necessity, the undermining of Schengen by countries is politically motivated, due to domestic political pressures on governments.

2.4 Defense cooperation

Vertical tension: Defense cooperation is taking place via different regimes. Shared efforts between the Council and the EP directly finance defense innovation. Unanimous decision-making in the Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP) and defense initiatives outside the EU-framework, however, bring up questions of inclusivity and flexibility.

New threats at home and in the EU's neighborhood (e.g. Russia) as well as emerging risks like cyberattacks are blurring the lines between internal security and external defense. In this context, EU citizens are increasingly looking to Europe for protection within and beyond its borders, because the scale and nature of these challenges are such that no Member State can successfully address them individually. A strong Europe in defense requires a strong defense industry.[34] Geopolitical shifts, a deteriorating security environment, the United States pressing Europe to take care of its own security and the Brexit have created a window of opportunity for the EU and its member states to get serious about its own security and defense.[35] As a result, they have decided to increase efforts in pooling and facilitating Europe’s military capabilities and enhancing its overall strategic autonomy.[36]

The main initiative in this area is the European Defence Fund (EDF). Initiated in June 2017 by the EC, and according to shared competence between the Council and the EP, the EDF aims to help Member States develop and acquire key strategic defense capabilities more quickly, jointly, and in a more cost-effective manner.[37] The EDF seeks to ensure the greatest possible support to the capability pillar of the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), an instrument in the EU Treaty that enables willing Member States to pursue greater cooperation in defense and security.[38]

The intergovernmental PESCO rule aims to fill the EU's strategic capability gaps and ensure cross-border availability and interoperability of forces. It aims to play to the respective strengths of each participating EU Member State, especially regarding the niche capabilities of smaller Member States.[39] The ambitiousness, inclusiveness, and implementation plans of the PESCO projects differ strongly, however. Some PESCO projects have been built on pre-existing, domain-specific knowledge and achievements at the EU or national level. Others will require new infrastructure and capacity-building to succeed. Signing up for PESCO, on the other hand, means an end to voluntarism in defense.[40] “Failing to comply with the conditions entails that Member States can be suspended by the Council. This is unprecedented in the field of European security and defense: PESCO would for the first time offer an enforceable legal instrument to keep Member States from back-tracking on their commitments. ”[41]

Defense cooperation also extends to the French-led European Intervention Initiative (E2I). E2I is a multilateral defense platform between the armed forces of European states “that are willing and able to carry out international military missions and operations, throughout the spectrum of crises.”[42] The raison d’être of the E2I is institutional flexibility. The majority of participating states share France’s assessment that EU decision-making processes and bureaucracy have proven incapable of leading to ambitious, time-sensitive deployments. Non-affiliation to the EU also has the benefit of allowing cooperation with CSDP opt-outs like Denmark and of tying the UK to wider European defense after Brexit.[43] The exclusivity of E2I as well as its position outside of both NATO and EU frameworks is problematic to Member States such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain, however.[44] These countries view the E2I as explicitly undermining the idea of European unity and causing tensions with countries outside E2I.[45]

Key take-away: Closer defense cooperation among EU Member States is now at the top of the European political agenda. Different regimes within the EU, such as shared competence in the EDF and intergovernmentalism in PESCO, have led to a strengthening of defense cooperation. At the same time, the E2I, raises questions of inclusivity and tensions with the EU’s machinery.

2.5 Sound Public Finances

Vertical tension: Italy’s disregard of the deficit rules has led to deep tensions with the EU, particularly with northern Members of the Eurozone. This has led to the EC’s unprecedented move to formally reject a national draft budget, showing the EU’s determination to uphold the Union’s fiscal rules against individual Member States.[46]

In October 2018, the EC issued the worst rebuke of a Eurozone government’s tax and spending plans in its history. By formally rejecting the draft budget of Italy, the EC took an unprecedented step that will force Rome’s government of the Five Star Movement and the League to rein in its spending plans or face fines under the excessive deficit procedure of the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact (SGP).[47] Rome’s refusal to budge marks the first time an EU State and Member of the Eurozone has ignored a formal reprimand from the EC since the EU’s fiscal rules were overhauled at the height of the Eurozone crisis in 2011. Mario Draghi, the European Central Bank (ECB) president, has also told EU leaders and Members of the common currency that undermining the budget rules would “carry a high price” for the Eurozone.[48]

Before the official rejection of Italy’s budget by the EC, Giuseppe Conte, Italy’s prime minister, clashed with fellow Eurozone leaders in Brussels over his country’s spending plans. Sebastian Kurz, Austria’s chancellor and Chairman of the rotating Presidency of the Council of the European Union from July to December 2018, sharply criticized Italy’s budget. On 22 October 2018, Kurz stated that Brussels should reject Rome’s plans unless there was a serious reevaluation of the budget proceedings: “‘Austria is not prepared to stand behind the debts of other states while those states are actively contributing to market uncertainty,’ [...] The EU ‘must show it has learnt from the Greek crisis.’”[49] Kurz was supported by the leaders of other fiscally hawkish Eurozone Members such as Finland and the Netherlands. This divide clearly signaled the increasing tensions between northern and southern Member States of the Eurozone.

After meeting with EC President Juncker on 12 December 2018, Conte promised a significant cut to Italy’s budget deficit target for 2019 as Rome bids to avoid sanctions from Brussels for breaching EU budget rules. The Italian prime minister said he would propose a government deficit of 2.04 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), from a previous target of 2.4 percent.[50] The EC described this result as good progress that will require further work in the weeks to come.

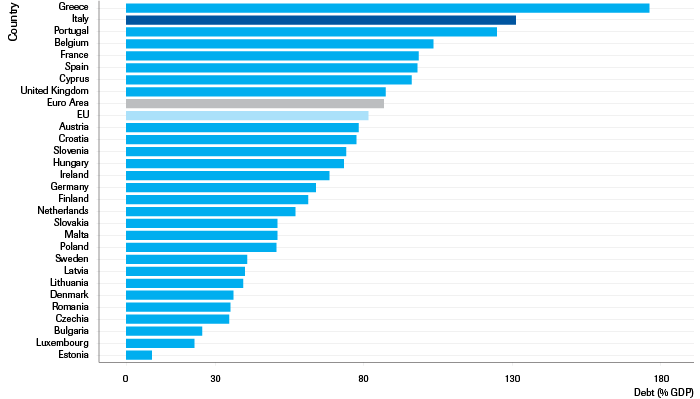

While Italy’s latest draft budget is within the Eurozone guidelines,

which specify that a budget deficit must remain under three percent of GDP, its

cumulative debt is enormous: more than 131 percent of GDP in 2017, far exceeding the

EU’s guidelines of sixty percent. Its debt burden, as a proportion of economic output,

is second only to Greece in the Eurozone (Figure 1). This new proposed budget would

drastically increase that debt, especially since Italy is not expected to achieve the

economic growth rates needed to reduce this.[51] The

danger, then, is that failing confidence in Italy’s ability to repay its debts could

trigger a renewed crisis in the Eurozone.

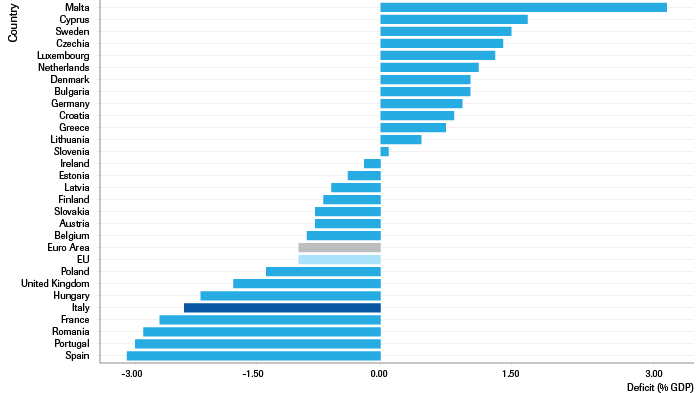

Apart from Italy and Greece, the Eurozone’s public finances are in good shape. The latest figures from Eurostat show that the bloc’s overall deficit stands at one percent of GDP (Figure 2). In comparison to a deficit of two and a half percent in 2014, this is a massive improvement.[52]

Key take-away: The breaking of the deficit rules by Italy has raised questions of compliance, i.e. whether and to which extent Member States are willing to comply with agreements made. Fearing a renewed financial crisis in the single currency area, Brussels, the EC, the ECB, and a number fiscally hawkish Member States are showing strong determination to force all Member States to abide by the rules of the EU’s SGP or face fines.

2.6 Tax harmonization

Vertical tension: Member States with the lowest corporate tax rates in Europe are opposing EU-wide tax harmonization efforts. While harmonization would create a level playing field by closing off avenues for tax avoidance by multinationals, Member States argue that such moves would damage competition in the single market. The EC has considered using extraordinary powers to break Member States’ resistance over blocked legislation.[53]

The focus on tax harmonization is high on the legislative to-do list of the EC. The EU’s current executive administration has direct plans to prevent tax avoidance by business players — mainly large-scale firms — operating in the EU. In October 2016, the EC announced the intention to proceed with major corporate tax reforms. These are meant to overhaul the way in which companies are taxed in the Single Market, “delivering a growth-friendly and fair corporate tax system.”[54] For more than seven years, the EC has floated the idea of creating a Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base (CCCTB). This would create a level playing field for multinationals on the Single Market by closing off avenues used for tax avoidance.[55]

However, for Member States like Belgium, Cyprus, Hungary, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, and the Netherlands, tax competitiveness is a key success factor for attracting big multinational companies and for strong economic growth. With some of the lowest corporate tax rates in the region, these Member States oppose the introduction of a CCCTB. Hungary’s Prime Minister Victor Orbán and Ireland’s Tsaoiseach Leo Varadkar also stressed in January 2018 that tax harmonization would damage competition amongst Member States in the Single Market. They further articulated their shared view that Member States should have the option to maintain a competitive tax policy and continue setting their own rates for corporation and income taxes.[56]

EU Tax Commissioner Pierre Moscovici has accused these countries of “aggressive tax planning” that undermines the “fairness and the level playing field in the single market.”[57] In November 2017, Moscovici stated that the EC was considering using its extraordinary powers to strip Member States of their veto power on tax matters to break resistance over blocking the CCCTB-proposal.[58] Moscovici further championed the plan put forward by French President Emmanuel Macron to tax digital companies based on revenues generated in EU Member States. So despite resistance from various Member States, tax harmonization within the EU is gaining momentum and may bring results on the short to medium term.

Key take-away: Member States with the lowest corporate taxation rates in Europe are clashing with the EC on adopting a CCCTB intended to deliver a fair corporate tax system. The issue has not yet been resolved, but the EU’s Commissioner for Taxation, supported by countries with a higher corporate tax rate such as France, is pushing for Member State action on this issue. For example, by supporting fair competition on the Single Market and diminishing tax avoidance.

3. General dimensions of the EU regime

Next to vertical tensions in specific policy dossiers, the question arises whether and to what extent tensions between the EU and Member States as well as within Member States are affecting the EU regime as a whole, i.e., the overall institutional and normative framework that has developed over the past sixty years. This section examines some emerging trends.

3.1 Consensus Principle

The consensus principle dominates day-to-day decision-making among EU Member States. This principle means that even in those cases where decisions can be made by voting, every possible effort will be made to arrive at a compromise that relies on the support of all Member States: Consensus.[59] So despite the rule of qualified majority voting (QMV), most of the Council’s legislative decision-making is made by consensus.[60] This informal rule fosters coalition-building within the Council, often resulting in compromise.

However, further analysis of the policy dossiers in this paper shows that the dividing lines between the Member States have intensified. These divides have become particularly evident in the North-South dimension on an economic level. In terms of the East–West dimension, divisions are notable in issues concerning the rule of law, while within the East–South dimension the focus is on migration.

It is therefore becoming increasingly difficult to make decisions through consensus. Leaving policy decisions on controversial issues to a vote poses the risk of obstructionism, with Member States withdrawing from the cooperative relationship of governing through consensus and retreating into a mode of voting and increasing intergovernmental decision-making.

3.2 Democracy and the Rule of Law

The principles of democracy and the rule of law on which the EU is based have also recently come under pressure. These principles are particularly pertinent when discussing Poland and Hungary, i.e., where governments have taken measures to restrict press freedom and judicial authority.

Recent actions taken by both the EP and the EC provide clear examples of increasing vertical tensions with these Member States. On September 12, 2018, the EP decided to launch Article 7 TEU proceedings against the Hungarian government following evidence of a lack of respect for the freedom of expression, academic freedom, and the rights of minorities.[61] Similarly, in September 2017, and after several warnings, the EC decided to launch Article 7 proceedings against Poland following concerns that the Polish government was undermining the independence of the Polish courts.[62] These first-time decisions by the EC to trigger this Article — which can lead to the suspension of a Member State’s voting rights in the Council — are clear proof of the increasingly strenuous relationship between the executive of the EU as guardian of the Treaty and individual Member States.[63] As Jean-Claude Juncker stated in the 2018 State of the Union speech, the EC will resist all attacks on the rule of law and Article 7 must be applied whenever the rule of law is threatened.[64]

As members of the ‘European club,’ Member States must comply with the EU’s basic values as formulated in Article 2 TEU. This article reads that the Union is “founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities. These values are common to the Member States in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail.”[65]

In the past decade, countries such as Bulgaria, Hungary, and Poland have moved away from respecting the EU’s liberal democratic norms and towards an illiberal democratic form of government. As a variety of factors such as increasing terrorist threats, migration, and economic stagflation have swept throughout Europe, governments have taken corresponding measures to prevent these attacks from reoccurring. In many cases this has led to “executive aggrandizement, i.e., the authoritarian executive branch of government legally seizing power from the legislative and judicial branches.”[66]

France, for example, has adopted aggressive counter-terrorism measures, extending the reach of the executive, which has restrained civil liberties.[67] Next to excessive executive action, countries like Hungary and Bulgaria also suffer from a democratic deficit. Bulgaria continues to suffer from organized crime and rampant corruption as well as ongoing marginalization of its Roma population.[68]

In similar fashion, Hungary struggles to maintain effective anti-corruption measures but passed legislation this year that targets the academic freedoms of the Central European University — funded by George Soros — as well as those of NGOs that receive funding from abroad.[69] In addition to Hungary, Bulgaria, Croatia, Romania and Greece are all rated at ‘Partly Free’ when it comes to Press Freedom. This is compounded by serious corruption and discrimination problems that Croatia, Greece, and Romania, in particular, face. It is Poland, however, that is currently facing the largest threat to upholding the democratic norm. Over the past year, several pieces of key legislation “including one that increased government influence over public broadcasters” were passed in fast-track procedures.[70]

Although the majority of Member States do not seem to be suffering from executive aggrandizement and/or a lack of adherence to democratic norms, there is a minority in the Southeast that is increasingly undermining the rule of law, respect for minorities, and the smooth functioning of national democratic institutions.

4. Conclusions

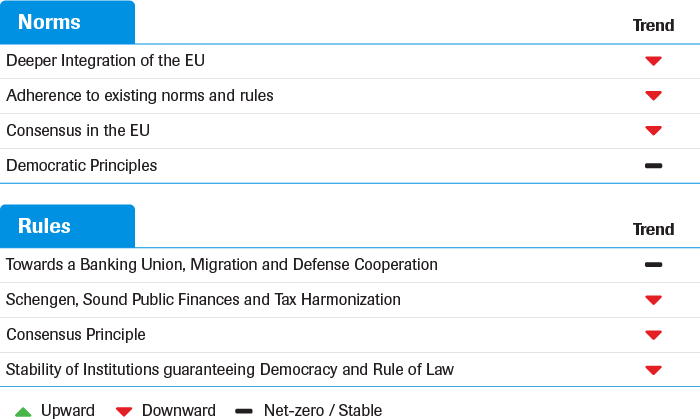

As a multilateral forum for negotiations, harmonization, and integration, the EU is increasingly confronted with rising tensions with Member States. In general, current EU cooperation in key policy areas is characterized by a lack of willingness to share or pool sovereignty. The overall result is a downward trend in compliance with existing rules and norms of EU cooperation (see Figure 3).

Efforts to complete the Banking Union are hampered by political and economic tensions along a North–South division, particularly regarding the creation of unfair risks and transfers of costs across countries.

In the migration dossier, and spearheaded by several CEES-countries, the Council has so far failed to reach a consensus in line with the EU’s norms of solidarity and shared responsibility with the frontier states in the South.

Despite the fact that migrant flows on all routes have steadily decreased, national leaders of countries from Denmark to Austria still feel the political need to look and act tough on this issue. In doing so, they are showing a lack of compliance with the principal underpinnings of the Schengen agreement and the four freedoms of the Single Market as set out in the Treaty.

Regarding sound public finances, the same lack of compliance applies to Italy. By breaking the deficit rules, Italy has raised questions concerning whether and to what extent Member States are willing to comply with existing agreements.

The EU’s efforts to cooperate on corporate tax reform are also sabotaged, in this case by the Member States with the lowest corporate tax rates who argue that mutual competition in this area is good for business.

Concerning defense cooperation, the French-led E2I initiative — outside both EU and NATO frameworks — is a recognition of the fact that EU decision-making and bureaucracy in this policy dossier is incapable of swift, ambitious, and time-sensitive deployments.

These developments in key policy dossiers suggest that the state dimension has gained traction in EU political decision-making. The heterogeneity of Member States and their exceedingly different national interests are defining factors that undermine the integration process as a whole as well as the norms and rules of EU decision-making.

However, the EU also shows that as a regime, it has the capacity to manage or channel at least some of these increasing tensions with and between the Member States. Italy’s disregard of the deficit rules led to the EC’s unprecedented move to formally reject a national draft budget. Supported by the ECB and fiscally hawkish Member States, the EC is showcasing the EU’s determination to uphold the Union’s fiscal rules against individual Member States. With success, as Italy is promising a significant cut to its budget deficit target for 2019 to avoid sanctions from Brussels for breaching EU budget rules.

In pushing for tax harmonization, the EC has also considered utilizing the extraordinary powers provided in the Treaty to break Member States’ resistance over blocked legislation.

Increasing geopolitical uncertainties have provided a window of opportunity for the Council and the EP to strengthen joint efforts in order to directly finance and pool financial contributions from Member States to jointly develop defense capabilities.

In upholding the Union’s liberal democratic norms in the Treaty and criticizing executive aggrandizement in certain Member States, the EU regime is showing the same kind of resilience that it shows in the financial sector. Both the EP and the EC are using powers granted to them by the Treaty to uphold the norms and rules inherent in the EU. Highly controversial policy dossiers such as migration, however, require a different kind of political capacity from the EU. They cannot simply be solved via the application of EU norms such as consensus-seeking. Traditional EU decision-making according to the rules of the ordinary legislative procedure is also not sought after. Instead, the European Council will need to move to pragmatic decision-making as seen in the case of the ethically and judicially questionable principles of the EU–Turkey deal in 2016.

So, while the overall assessment of EU cooperation in key policy areas in this paper is negative, the EU regime is still alive and kicking. And as the EU will increasingly have to deal with heavily political dossiers that require the sharing of sovereignty, vertical tensions between EU Member States on the one hand and the EU on the other are likely to continue and intensify. Whether or not the EU regime will be able to successfully channel and manage these tensions is ultimately up to the Member States.